Sound Art in Flanders: A Growing Discipline

Since the 1990s sound art in Flanders has continued to expand through national and international impulses, and has now become a dynamic scene with its own specialised artists, organisations and production platforms. Over the last decade, the discipline has also received full recognition within the Flemish arts landscape.

In comparison to other European regions and countries, the field of sound art in Flanders is a rich ecosystem with With a multitude of organisations and artists who are active around the medium of sound in various ways. With Brussels as its driving force, it allows a very young and international scene to fully resonate.

This article gives insight into the players in Flanders in the field of sound art. The perspective is broad, and it includes interconnections with other disciplines. Here, you can read how the various actors have grown over the years and how the medium of sound is today bridging the gap between audiences, the arts as a whole and the ever-faster changes in technological, social and ecological circumstances.

Video Sound Art in Flanders (with English subtitles)

We are trying to show content from Vimeo.

Kunsten.be only uses minimal cookies. To view content by a third party website, this site can place additional cookies. By continuing to browse you are agreeing to the use of those third party cookies.

Read more about our privacy policy?

A Definition of Sound Art

A Definition as an instrument

Sound art is a hybrid, autonomous art form that finds itself between other art disciplines and sectors, and which centres on sound in widely diverse forms. These range from open-air sound installations and three-dimensional speaker arrangements to installation art, podcasts, listening sessions, sound walks, participative performances, interdisciplinary creations, experimental music, performative concerts, audio-visual work, virtual reality or game environments, and more.

It is impossible to provide an unequivocal definition for what sound art is.[1] This has, among other things, to do with how the field evolved: it did not grow out of a single, specific fascination for sound within a given discipline, but developed from within music and the visual and audio-visual arts, and did so in different places around the world.

Sound art is a fairly recent concept. From the early 2000s on it became a collective term for something that had already existed for a very long time, something that has been connected to music and to art as a whole, in the form of a search for new sounds, forms, objects, technological media and spaces that lie beyond those of the orchestra or gallery space.

The makers of sound art are usually artists with widely diverse backgrounds, including musicians, architects, makers of radio broadcasts, sound designers, multimedia artists, scientists, anthropologists, archivists and so on. They are often both musicians and sound artists, for example, or architects and sound artists, and so on.

Together with what are still new discoveries in sound and media technologies (often in the wake of political and economic developments),[2] they give form to this cultural field, ‘which often seems diffuse and unclear’.[3]

Laura Maes, a researcher at the University of Ghent and sound artist, has formulated a number of traits that characterize this hybrid field. One might think of working with different sound sources and materials: electronic, electro-acoustic and/or acoustic. An example is the 2018 work Polyhedra by artist Floris Vanhoof, an installation consisting of an orchestra of loudspeakers with 50 different geometric forms, with built-in speakers.

We are trying to show content from Vimeo.

Kunsten.be only uses minimal cookies. To view content by a third party website, this site can place additional cookies. By continuing to browse you are agreeing to the use of those third party cookies.

Read more about our privacy policy?

It is also characteristic of sound art that its creators often make site-specific works, outside the concert hall or gallery space, allowing themselves to be inspired by the ecological environment: in urban public spaces or on open-air sites, such as landscapes, rivers, seas or forests, or empty buildings. The inherent acoustic or technical characteristics of the given space of the work are a determining factor for the experience.

This means that the distance that has traditionally been maintained between the viewer or listener and the work of art or its performers, in both museums and concert halls, has largely disappeared. Visitors can often walk in or around a work of sound art and are even encouraged to experience the sound with their entire bodies.[4]

in this way, sound art has broken with the musical practice of being centred around the composition, and explicitly creates a framework or context around the production and perception of sound.

In 2016, in Belgium, artist, educator and researcher Esther Venrooy wrote an On the Process of Becoming Silent and Listening, as a starting point for a dialogue about perceiving (looking, listening, feeling) a space. In it, she does not so much delve into the tangible things that give form to a space or environment, but describes the way we perceive a space by means of stillness and listening.[5]

A work that plays with this idea is the 2012, site-specific installation, Bruit Blanc, by the Brussels-based artist duo, VOID Collective.[6] The installation is an aesthetic reflection on the existing discipline of sound archaeology: an attempt to read all sounds that have been absorbed into every surface in the course of its history, based on the idea that sound leaves traces of its interaction with every material by way of the natural phenomenon of sound erosion. All of these sounds sketch an image of the acoustic history of a location.

Main lines in the international sound art scene

The new hybrid field of sound art received important impulses from historic and contemporary art movements, including Fluxus, Musique Concrète, electronic music, land art, the ethnographicturn, radio art, and transdisciplinary and participative arts.

A number of major international movements include field recording, sound art based on installation and/or technology, soundscapes and acoustic ecology, sound sculptures or sound objects, sound as acoustic, relational or physical phenomenon, sound walks, electroacoustic composition, performative or acousmatic sound, or sound as a social medium.

Today, we also see interesting in-between forms, between electronic club music and sound art with hybrid forms of sampling, computer music and noise.

The development of this art form goes hand in hand with the evolution of new media. Never before has listening to recorded sound been so prevalent in everyday life as it is today. We need but think of the emergence and prevalence of headphones, portable speakers and recorders, the excellent recording quality of smartphones, podcasts, overall democratization of access to music through online platforms, and so on.

In a world that was long focussed on the visual, listening is now on the rise. A growing and extremely diverse group of artists are implementing these new forms and awareness of listening and the acoustic environment in their artistic practices.

Listening as revolution

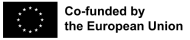

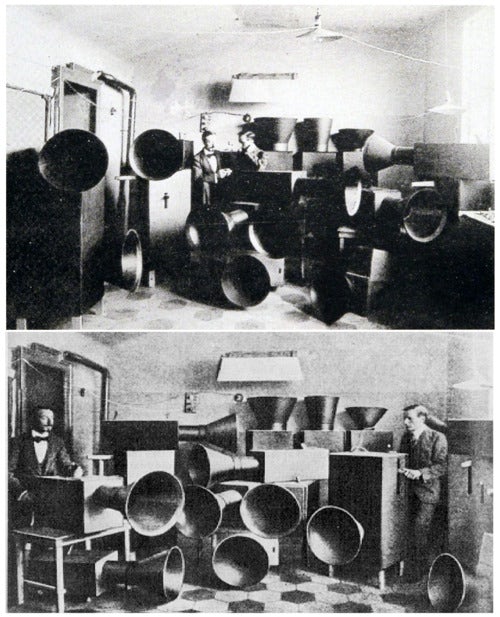

The early ideas go back to Italian Futurism and L’arte dei rumori, a manifesto written in 1913 by composer and instrument builder Luigi Russolo, as a reaction to the noise and sounds of the Industrial Revolution, going back to the 19th century. He proposed bringing listening to sounds and noise from the background to the forefront, as compositional material, irrespective of tonality.

In order to make these sounds audible, he developed his intonarumori, a series of instruments that can be seen as forerunners of later sound art works.

In 1948, in France, Musique Concrète, conceived by Pierre Schaeffer, a composer who worked for French Radio, represents a definitive breakthrough for recorded sound as a raw, musical material.

At about the same time, American composer John Cage was developing his own focus on listening and on re-examining what music is. In 1952, his work, ‘4’33’, initiated the idea that every sound can be music and that even listening to silence can be a musical experience.

This new listening reached a new generation, which included La Monte Young and Eliane Radigue. Composer and accordionist Pauline Oliveros subsequently formalized the art of listening, more specifically as Deep Listening, a pioneering philosophy and practice that centres on attention to one another by way of listening. A younger generation of artists and composers are still – and it seems increasingly – being nourished by Oliveros’s ideas, work and mentoring.[7]

In Canada, composer and field recorder Murray Schafer took this enhanced listening further. He used recorded sounds to form soundscapes or Paysages Sonores and launched The World Soundscape Project, an international practice around acoustic ecology and sound as it relates to the environment.

His assistant Hildegarde Westerkamp investigates the relationship between taking walks and sound and shaped early ideas about the practice of Sound Walking.

Over the years, sound has evolved from its subservient role in, for example, film and theatre, to an independent creative medium in its own right. Sound art has evolved from a rather obscure niche position into a dynamic discipline with its own wide audience. The relationship between sound, space and materiality is also further evolving in architecture, visual art, installation and media art.

This brief description provides only a very limited introduction to the evolution of sound art. There are many others, including Karlheinz Stockhausen, Alvin Lucier, the Sonic Arts Union and Halim El-Dabh, who have also generated important developments, but we are not able to expand further here. To learn more about the history of sound art, please refer to other publications.[8]

Sound Art in Flanders

Pioneers

Tendencies in the international art world find resonance in Flanders. A number of Flemish composers and artists played leading roles in the early developments in electronic, spatial and acousmatic music.

In 1953, composer Karel Goeyvaerts (1923-1993) created one of the world’s first electronic compositions: Number 5 with Pure Tones. The work is built up from a mathematical construction of sinus tones and exudes purity, thanks to its abstract sound structure.[9]

A second important anchor point was the Philips Pavilion at the Expo 58 world exhibition in Brussels, an event that inspired Belgian, as well as other composers. The space for spatial electronic music was designed by architects Le Corbusier and Iannis Xenakis (who was also a composer). Visitors could experience Edgar Varèse’s electronic music composition, Poème électronique, through 425 loudspeakers with slide projections on the walls.

In Ghent, in 1963, the Institute for Psychoacoustics and Electronic Music (IPEM) was founded as a collaboration between the public broadcasting service (then the BRT, now VRT) and Ghent University (then the RUG). The Institute had a twofold mission: to produce work for radio and television on the one hand, and to conduct innovative research into sound technology and electronic music on the other.

Under the leadership of composers such as Louis De Meester (1904-1987),[10] Karel Goeyvaerts and Lucien Goethals (1931-2006) the IPEM expanded at an international level, into a production studio where composers and artists could become acquainted with the newest technologies, with the practice of field recording at its core. With the rise of digital media, from 1987, the laboratory was redesigned as a university research lab.

Always operating on the line that divides art and science, the IPEM was for a very long time one of the few places in Belgium where sound artists could develop their work. They later also experimented with new technologies, such as virtual and augmented reality, biofeedback, interaction, immersion, 3-D sound rendering and motion tracking. Today, the IPEM – and more specifically its Art-Science-Interaction Lab (ASIL) with a.o. Guy Van Belle in its artistic team – is still an important place where art, technology and science all come together.

In the 1970s, Joris de Laet worked with Lucien Goethals at IPEM, and in 1973 he started the Studio for Experimental Music (SEM), where he brought together composers, musicians, and sound artists to experiment with sound and composition.”

Godfried-Willem Raes and Monique Darge visited IPEM as young musicians, and in the 1970s, they foundedthe Logos Foundation. It was the first Flemish research and production centre for sound art and experimental music, with a focus on technology, robotics and avant-garde music. Through the years and together with a number of other driving forces, such as Guy de Bièvre and Laura Maes, they created Het Robotorkest (1980-) and such mobile installations as the Pneumafonen (1981-), an interactive collection of pneumatically driven sound sculptures.

Pneumophone is a collection of pneumatically driven sound sculptures. Flutes, single reeds, lips, tongues, double reeds, mirlitons, water organs, wind membranes and so on form the individual voices of each pneumaphone. Sitting, lying, rolling over or rocking on the yellow pillows causes the air in them to move. Hoses transport this air to the pneumaphones, one for each pillow. Depending on the type of movement on the pillow, the transfer of air changes, and so does the sound. Pneumaphone makes motion both tangible and audible.

In the late 1970s, composer and artist Baudouin Oosterlynck was one of the first people to make an object that rendered sound as a tangible phenomenon. These are sculptures that visitors could walk around with, and – as an extension of their own hearing – receive and amplify sounds, such as, for example, the frequency spectrum of silence. In this way, Oosterlynck investigated the behaviour of sound in specific places, depending on the body and the position of the listener.[11]

In Brussels, in 1984, composer Annette Vande Gorne (1946 -), who studied with Pierre Schaeffer at the Conservatory of Paris, organized the first festival for electroacoustic music: L’espace du son, centred on the Belgian variant of the acousmonium (a system with loudspeakers of different sizes and shapes, initially designed by Francois Bayle in 1974).[12]

Acousmatic music focusses on listening itself, without being distracted by the source of the sound. This musical form has been evolving since the latter half of the twentieth century – as did cinema – in studios, with sound recordings and transformations of these sounds. During concerts, these are again made three-dimensional and spatial through orchestras composed of loudspeakers.

Today, the acousmonium is an element used by the Influx – Musiques & Recherches research group and can still be found at festivals, including Ecotone, where a young generation of artists, such as electroacoustic composer Caroline Profanter and others, share their work.

In 1999, the electroacoustic composer Charo Calvo graduated from the Brussels Conservatory under Annette vande Gorne. She developed her own multichannel compositions for the performing arts and other venues. In collaboration with Wim Vandekeybus and the Ultima Vez dance company, she has since created the soundscape for the 2020 performance, Hands Do Not Touch Your Precious Me.

From 1996 to 2008, the Happy New Ears festival in Kortrijk was one of the first sound art festivals in Europe. Under the leadership of curator Joost Fonteyne, it was an important catalyst for the local Belgian scene, with residencies, international exchanges, coproductions and an exhibition of sound art in public space. Happy New Ears then evolved into the Festival van Vlaanderen Kortrijk and the operations of Wilde Westen, with the biennial Klinkende Stad exhibition. Kortrijk was consequently one of the most important places where exchange at the international level found its way into the local landscape.

The Europe-wide Resonance project took place between 2010 and 2014.[13] As a sequel to the international work No Music – Ear Pieces (a series of ‘compositions for the ears’), artist David Helbich developed the first in an important series of audio walks: a guided walk through public space in which different ways of listening and the sensory experience of listening are central.

We are trying to show content from YouTube.

Kunsten.be only uses minimal cookies. To view content by a third party website, this site can place additional cookies. By continuing to browse you are agreeing to the use of those third party cookies.

Read more about our privacy policy?

In the same time frame, sound artist Franziska Windisch also developed walks as an art form, with chalk lines, sound and the exploration of buildings or undeveloped land. In 2009, sound artist Els Viaene undertook The Mamori Expedition, a walk in the Brazilian Amazon jungle that was later transcribed into a wooden installation with sounds from the river that she followed during the expedition.

In 2021, various organizations from today’s art and music landscape, including BNA-BBOT, Overtoon, Q-O2, Jubilee, Beursschouwburg and Soundtrackcity developed Tracks, a platform and interactive map with artistic sound walks in and around Brussels.

In addition to the above, in Netwerk Aalst and theVooruit Arts Centre (with programme director Eva De Groote), sound art is also included as a part of their scheduled exhibitions and music programmes.

In the 1990s and the first two decades of the new century, a variety of new locations and audiences evolved around the practices of specific artists, artist groups and/or curators. Their respective visions and approaches to sound art helped shape a certain listening culture that has since become characteristic for each organization or space.

One thing that is characteristic of this period is what Linnea Semmerling refers to as ‘the rehearsal’, in which each event, investigation or experiment seems to be a rehearsal or practice session with the parameters and characteristics of a given space, audience, ways of listening and diverse auditive media.[14] This practicing and rehearsing gradually evolved into greater professionalization and perpetuation of a polyphonic ecosystem.

We are trying to show content from Vimeo.

Kunsten.be only uses minimal cookies. To view content by a third party website, this site can place additional cookies. By continuing to browse you are agreeing to the use of those third party cookies.

Read more about our privacy policy?

New dynamic in Brussels

Today, the hub of this landscape is Q-O2, the Brussels workplace for experimental music and sound art. The organization grew from an ensemble operation in the 1990s to a dynamic arts organization, housed since 2006 on a former industrial site in Brussels. It is a place where every Flemish sound artist touches down and finds support during the course of their career, and which is also well known internationally.

Musician, curator and coordinator Julia Eckhardt, together with a team of other artists, including Ludo Engels, Henry Andersen and Caroline Profanter, ensures that Q-02 is a place for the development and presentation of sound art, with a focus on the artistic process. All year round, they provide facilities for artists in residence in association with monthly presentations and the annual Oscillation Festival.

Through international projects, the Q-O2 organization puts an emphasis on reflection and has a stimulating role for the field as a whole. With series of podcasts about, for example, gender and music, or by way of publications through their own Umland publishers, they put diversity within this sector on the agenda. The organization has initiated a range of Europe-wide projects with local repercussions, including Sounds of Europe (with a focus on field recording)[15] and SoCCoS (centred on exchanges and residencies in specific contexts).[16] One important one-time festival was Tuned City Brussels, which took place in 2013 and centred on the auditive identity of the capital city .

A second Brussels-based organization that is directed toward development and production is the Overtoon platform, founded in 2013 by artists Christoph De Boeck and Aernoudt Jacobs. Over the years, Overtoon has provided important impulses and incentives to the fields of installation art and media arts, which has resulted in international, monumental works of art, such as the 2015 Heliophone installation by Aernoudt Jacobs, which transforms sunlight into sound, or Behind the Tune, from 2020, by sound artist and field recordist Dominik ‘t Jolle, a collaboration with the BRAI3N brain research centre about the phenomenon of tinnitus.

We are trying to show content from Vimeo.

Kunsten.be only uses minimal cookies. To view content by a third party website, this site can place additional cookies. By continuing to browse you are agreeing to the use of those third party cookies.

Read more about our privacy policy?

Overtoon focusses on the research, production and distribution of sound art. The platform evolved from the need to create structural frameworks around the development and production of sound art for both young and mid-career artists. Overtoon engages in long-term collaborations with artists who in turn can make use of a place to work, production facilities, technical expertise, artistic feedback and administrative and financial support.

In addition, research residents can find a place in the Overtoon studios for shorter periods of time, in order to investigate a specific aspect of their work that is related to sound. The production platform also has a broad international network that connects artists with curators in diverse programmes and exhibitions. Today, for example, there is the Oscillations international exchange programme, which investigates the tension between acoustic and visual forms of art from the perspective of the maker.[17]

Nourished in part by these two organizations, the epicentre of the sound art landscape is indeed grounded in the cosmopolitan culture of our capital, where the majority of facilities for higher education in sound are found and international artists settle in order to work, often in shared, temporary studio spaces.

We are trying to show content from YouTube.

Kunsten.be only uses minimal cookies. To view content by a third party website, this site can place additional cookies. By continuing to browse you are agreeing to the use of those third party cookies.

Read more about our privacy policy?

One example of an artist-run complex of this kind is Brasserie Atlas in Anderlecht, where a group of artists live and work since 2016, and where residencies and events take place. In addition, Webradio Lyl is expanding on its Brussels location (in addition to Marseille and Paris), together with DJ and sound artist Mika Oki.

The great strength of this location, according to resident and sound artist Amber Meulenijzer, is not only the space that it offers for experimentation and innovation, but also the possibility of presenting work in different stages, in an informal way, and being able to discuss it with others. This is something that is more difficult in larger structures, although there is considerable need within the sound landscape. This old brewery building is moreover one of the few places where both the French-speaking and Dutch-speaking fields come together, bringing its own challenges for the Flemish field.

For many, the noise and chaos of the metropolis is a huge inspiration. As a reaction to the noise pollution of the city is Stilte/ruimte, a ‘stimulus-free space’ devoted to the awareness of the importance of silence.[18]

We see this theme recur as well in the work of Brussels-based field recordists, such as Joost van Duppen and Stijn Demeulenaere. Together with filmmaker Jan Locus, Demeulenaere created the 2020 film MurMur, based on field recordings made in the Ganshoren swamp in Brussels during the dawn chorus.

We are trying to show content from Vimeo.

Kunsten.be only uses minimal cookies. To view content by a third party website, this site can place additional cookies. By continuing to browse you are agreeing to the use of those third party cookies.

Read more about our privacy policy?

Since January 2011, the Week of Sound of Brussels presents a series of events that revolve around sound and noise. The objective is to bring better understanding of sound to audiences and help all those engaged with society to realize how important a sound environment is.

The role of art houses: production and presentation

An important recent step is that a number of major art houses have taken up sound art as a segment of their operations. Among other things, this has to do with the broad audience reach of this hybrid art form, which, in comparison to visual art, appeals to audiences in a very direct and experiential way.

Sound art is a physical, sensory experience which, thanks to its immersive and meditative character, is able to move broad audiences in a very accessible way. It is indeed not a surprise that the discipline is currently growing so explosively and has been so warmly embraced by the public.

Long months of empty concert halls during the COVID epidemic meant that sound art was one of the few possible ways to experience live forms of culture. Musicians in electronic music circles experimented with installation art and organizations commissioned artistic works for public space, based on sound.

One of their series is Beyond Music, for performative sound art and music in a spatial context. It offers an experimental laboratory for makers and musicians who operate between the disciplines by bringing sound into relation with image, movement, spatiality, musical meaning and mental projections.

Since 2015, STUK, huis voor dans, beeld en geluid has operated around sound art. In just a few years, programme director Gilles Helsen has been expanding the art centre’s musical activities into a hybrid and vivacious hub for concerts and artists-in-residence, in which sound itself is the focal point. With adventurous music and accessible listening formats, STUK has been able to bring together a primarily young audience of people who find themselves in the experience of listening and the exploration of unfamiliar sounds from contemporary music and sound art. During the last decade, sound art has become a larger part of the programme, which, along with performance evenings, also includes exhibitions in public space.

STUK is also coproducer of diverse new creations, and in this framework offers shorter-term residencies for development. Thanks to workshops and available trajectories, their programming is aimed at a diverse audience: from children and families to art lovers, as well as upcoming and professional artists.

STUK also hosts various festivals, such as Artefact and Hear Here, with exhibitions of sound art and performance. STUK, Q-O2, Musica and C-TAKT together organize the annual Showcase Emerging Sound, a trajectory for young, promising sound artists in Belgium who are exhibiting their work at STUK. This showcase presents the diversity of the Belgian sound landscape while giving the upcoming generation of sound artists a helping hand.

In November 2021, Concertgebouw Brugge also announced that in addition to music and dance, sound art would become one of the major disciplines presented at the concert hall. The exceptional architecture of this building has for some years already hosted Circuit, an interactive series that includes such sound art works as the permanent installation, Poème Electronique, by Edgar Varèses, and a listening model of the building, created by Nu Architects and composer and artist Heleen Van Haegenborgh.. This work in turn includes a wall-sized timeline of the European history of sound art, allowing audiences to place what they are experiencing in an art historical context.

By bringing sound art into its concert and exhibition operations, the Brugge Concertgebouw organizers, audiences and makers are encouraged to expand their horizons and inspire one another to experience art more deeply, yet in an accessible way. For example, the concert hall commissions artists to create new works, ranging from installations, sound walks or performances to the development of new works with a musical and investigative approach to sound.

All of this is, among other things, presented as part of Deep Listening Days. Since 2021, it is also possible to listen to The Sound of Cobblestones, by Duobaan XL, a musical and audio-visual trajectory about the memory of the city of Brugge. In their educational programming, the Concertgebouw creates innovative formats and new networks between art organizations, sound artists, and socio-cultural societies and their audiences.

Sound Art in public space: practices and players

In often unexpected places, all around Belgium, it is possible to experience sound art in public spaces. There has even been a new sub-field of artists, organizations and temporary or longer-term initiatives as a result of this practice.

In the empty dune landscape of the Zwin Nature Reserve in Knokke-Heist, for example, we find the permanent installation, Listening Dune, completed in 2016 by sound artist Els Viaene and the international British field recordist Chris Watson. In 2020-2021, the Krottegem neighbourhood of Roeselare was one of the hosts for the multinational project, Sounds of Our Cities: Sound Art and Urban Context.[19]

The relationship between sound, urban landscape and architecture is also investigated in the work of the Brussels artist and researcher at KU Leuven, Caroline Claus. In her book, Studio_L28 – Sonic Perspectives on Urbanism (2018), she explores different ways of integrating sound in the process of urban planning and the role of sonic vibrations in the development of public urban space.

In her 2021 project, Q(ee)R Codes – Nouvelles frontières BXL, radio artist and sound artist Anna Raimondo examines the presence and experiences of cisgender, trans and queer women and non-binary people in cities.

We are trying to show content from SoundCloud.

Kunsten.be only uses minimal cookies. To view content by a third party website, this site can place additional cookies. By continuing to browse you are agreeing to the use of those third party cookies.

Read more about our privacy policy?

Since 2000, the Musica Impulse Centre in Pelteen has been building a collection of sound art works in public space in and around the Dommelhof Provincial Domain: Het Klankenbos is currently made up of twenty permanent sound art works by international artists, including Hans Van Koolwijk, Pierre Berthet and AnneMarie Maes.

This collection – unique in Europe thanks to its size – wants to encourage audiences to more conscious listening and actively engaging with sound and the acoustic environment. In addition, Musica also holds workshops, residencies (together with C-TAKT) and festivals, such as the biennial OORtreders Festival, with a sound art exhibition in public space and a performance programme.

In collaboration with such international partners as Intro In Situ and Soundtrackcity, in 2014, former Musica director, composer and research professor Paul Craenen established Klankatlas: an online sound map that makes musical heritage in public space visible and audible, and for which new works are created. Today, the organization is project leader for the European project, Sounds Now, focussed on curating diversity in sound art and contemporary music.[20]

In addition to permanent installations, we are currently seeing growing interest in including sound art in all its forms in art routes and venues, art walks and festivals. STUK’s Hear Here sound art exhibition is an example. It comprises a walk along which sound art is presented at various historic heritage locations in the city centre of Leuven.

Radio, stories, documentary: practices and players

Today, sound art that evolved in the margins of documentary radio is flourishing, and has a scene all its own, including ‘breeding ground’ locations, production studios and festivals. For a long time, creative radio served as a counterweight to the unilateral culture of public broadcasting and sought to complement it by creating unique forms of collectivity and alternative voices. Productions for radio experimented with the foundations of the medium itself, such as electromagnetic waves, narrative structures, radio tools, sonification and participation.[21]

Since 2000, the bilingual organization Bruxelles Nous Appartient – Brussel Behoort Ons Toe (BNA-BBOT) has been engaged in making art audible. In a participative and co-creative way, they document the multiplicity of voices in the city of Brussels. Their collection of stories and sounds is permanently accessible by way of their online databank and the Brussels Sound Map, which everyone can listen to and/or add their own sounds.

With more than 24,000 recordings, this collection is the largest participative sound archive in the world. It provides an ethnographic insight into the multiplicity of voices in the life of the capital. This material forms a source of social, cultural and historic knowledge and is used, among other things, for documentary creations for radio. With workshops and its own recording studio, BNA-BBOT provides space and guidance for anyone who wishes to engage with the social and documentary aspects of sound art. In 2022, they organized the Brussels Podcast Festival.

Together with BNA-BBOT, in 2021, media artist Marthe van Dessel transformed the Sint-Anna Fountain in Brussels into a radio receiver and broadcaster. Using a pump, salt water, and the water that shoots into the air up to a certain height, the fountain is now an antenna that broadcasts both image (SSTV) and sound (FM). In this way, a public space becomes a shared and autonomous interface for trans-local telecommunications.

Radio artist, composer and vocalist Aurélie Nyirabikali Lierman is inspired by the narrative power of abstract sound and music. She initially worked for radio and was a presenter for VRT, but has subsequently devoted herself to her artistic work, which balances between radio, installation, performance and voice art. Central to her work is her extensive collection of both rural and urban field recordings and soundscapes from contemporary East Africa. She has won a number of awards for her work for radio, including Monophonic 2014 (Brussels) and Anosmia (a radio composition around the theme of the Rwandan genocide), as well as the 2019 CTM Radiolab prize in Berlin.

We are trying to show content from YouTube.

Kunsten.be only uses minimal cookies. To view content by a third party website, this site can place additional cookies. By continuing to browse you are agreeing to the use of those third party cookies.

Read more about our privacy policy?

Although creative radio was for a long time more prevalent in southern Belgium, it is today also a very vivacious field in Flanders, connected through such platforms as Klankverbond[22] and the Luyster presentation platform, and linked to the radio education facilities of the RITCS in Brussels, Woord, at the Antwerp Conservatory, and Postgraduate Podcasting at Artevelde University of Applied Sciences, with such artists as Eva Moeraert, Lucas Derycke, Wederick De Backer and Katharina Smets.

In addition to her artistic practice, Katharina Smets is also a storytelling instructor at the Royal Conservatory in Brussels, founder of In The Dark Belgium and curator for, among others, the Oorzaken Festival, a festival for narrative radio and podcasts at the Brakke Grond Flemish cultural centre in Amsterdam.

These frontiers are also investigated at Nieuwstedelijk, located in Hasselt and Leuven. This organization is devoted to independent audio and, from there, building a bridge to theatre. They annually lend their support to two young creators, currently Lotte Nijsten and Gillis Vanderwee, and previously LucasDerycke, who developed his Hangar data production in 2021.

Interface between installation, performance and new media

Myriam Van Imschoot employs the theatrical power of sound to engage the imagination in sound poetry, vocal pieces and video and sound installations. One example is the 2015 vocal performance, What Nature Says, a production for six performers who mimic their natural environment exclusively through their voices and bodies. In 2021, Van Imschoot founded the artist-run Newpolyphonies, for transdisciplinary vocal art and artistic voice practices.

Tuning People, including sound artist Wannes Deneer, among others, developed sound installations that could subsequently become part of theatre productions and consequently explore the possibilities of sound art in theatre. In 2022, Tuning People dissolved the collective, so that its three members could better develop their own work.

A yet different branch of sound art exists which approaches sound art as a form of performance. One example is Volta, by Yann Leguay, who developed an instrument from a powerful plasma loudspeaker and an electric arc of about 50 kV, producing sound between two electrodes. The arc acts as an electric string, with settings for tuning, creating harmonies and resonances so powerful they cause magnetic disturbances. The performance touches on the dematerialization of sound in the form of a sound wave and as a powerful means of resistance and control. Sound as a space for resistance or simply influencing from above is a central factor.

We are trying to show content from YouTube.

Kunsten.be only uses minimal cookies. To view content by a third party website, this site can place additional cookies. By continuing to browse you are agreeing to the use of those third party cookies.

Read more about our privacy policy?

Artist Lukas De Clerck also creates sound performances by way of installations and the invention or reinvention of instruments. With Abruit, he constructed a hiding place or shelter with countless arteries that connect the central core with sound objects distributed throughout the space. The result is a spatialized multi-instrument that is situated somewhere between installation and performance.

Participation: co-creation en education: practices and players

The history of recorded sound is closely associated with the question of which voices we wish to reinforce and which we do not. There is growing interest in the social role of sound, as a connection between different persons and places, but also as a space for self-development and the development of certain skills. This is not about simply making something audible, but also about the unique nature of listening itself, listening to the multiplicity of voices, perspectives and narratives that all exist simultaneously alongside one another.

Conceptually, this idea is often linked to polyphony. Musica Impulse Centre (see above) helps guide artists, participants, organizers and curators in artistic musical experiences by way of participative and educative projects centred on sound and music. The organization has developed diverse art-educational formats around the Klankenbos collection, in which they stimulate local residents (from the very youngest to adults), amateurs and professionals to take part in artistic creation processes. They added the new participative artwork, Doors of Listening, to their collection in 2020.

We are trying to show content from YouTube.

Kunsten.be only uses minimal cookies. To view content by a third party website, this site can place additional cookies. By continuing to browse you are agreeing to the use of those third party cookies.

Read more about our privacy policy?

For 21 years, Bruxelles Nous Appartient – Brussel Behoort Ons Toe (BNA-BBOT), under the leadership of Brussels-based philosopher Séverine Janssen and field recordist Flavien Gillié, has operated around sound in both a participative and multi-sectoral way, for and by the residents of the city. Their mission is to give everyone the opportunity to speak, as a form of self-reliance and as a basis for artistic creation embracing a multiplicity of voices.

BNA-BBOT has initiated long-term projects and workshops in neighbourhoods, city districts and schools, around certain themes through which they motivate residents and actors in Brussels to tell their own stories, histories (fictional or otherwise) and futures, and to express these in sound.

The publication, De methode zoals ze soms is, misschien was of zou kunnen zijn (the method as it sometimes is, maybe was or could be), reflects on these methods involving participation and co-creation with sound and voice within a major metropolitan context. Another important function for BNA-BBOT is its role as an archive of participative processes and voices from the arts, in order to comprehend what is often a hidden multi-voiced reality within art projects.

In 2003, KONGvzw began Traject, an educational exchange project between Nord Pas de Calais and Flanders, in which children could auditatively reflect on their daily commute between home and school. In 2005, Martine Huvenne and sound artist Stijn Dickel reorganized the project as the independent, structural arts organization, Aifoon.

Aifoon sees listening as a critical and co-creative medium for achieving an artistic, social and cultural dialogue. They investigate different methods of using co-creative processes to engage a broad audience with the many facets of listening-based art.

As a reaction to the visually dominated world, Aifoon wants to auditatively stimulate people and take steps towards a rich, active listening culture. As a nomadic arts organization, in partnership with other organizations, they open up possibilities for listening and what it can do for and with someone’s imagination and creativity. Aifoon also actively investigates how people can take active part and personally intervene in the listening environment.

For example, in the Phonorama project, residents and passers-by in a given neighbourhood are challenged to record valuable and fascinating urban sounds. As a final step in the process, the neighbourhood selects 20 sounds to be buried in a time capsule in public space. In 20 years, the capsules will be opened again and listened to by the listeners of the future.

Sound Art is everywhere

There are moreover smaller organizations, including ChampdAction (initiated in Antwerp in 1988 by Serge Verstockt, together withAnn Andries), which also support sound artists, as well as contemporary music, further helping the discipline to gain prominence outside established sound art circuits.

Although sound art tried for a long time to keep itself separate from the busy waters of the music field, we today see many new in-between forms, such as between sound, electronic music and night life. As a hybrid art form, sound art is winning a larger and larger role at diverse festivals and at such venues as the Beursschouwburg, Ear To The Ground (Bijloke), Kraak Festival, Horst Festival, Eastern Daze, Courtisane, Lunalia, Zindering Festival, Ruiskamer (Vooruit & MIRY Concert Hall), Schiev Festival, Kunstenfestivaldesarts, GLUON, Plan B, iMAL, Argos, Het Bos, Middelheim, S.M.A.K., Recyclart, KANAL Centre Pompidou, Z33, Les Ateliers Claus, STORMOPKOMST and Kaap, as well as such artist-run organizations as De Nor en Pleasure Island.

Opportunities for a Growing Discipline

This ecosystem is interconnected by way of such consultative umbrella organizations as the Platform for Audio-visual and Media Arts (PAM) and is characterized by the many organizations, each with their own origins and representing a multitude of presentation formats.

Although sound art is everywhere today, there remain many opportunities in the realms of diversity, gender and decolonization of this form of art. The story of its evolution indeed often begins with the history of Western art and technology. One work of art that questions this fact is Johari Brass Band, by Sammy Baloji. It comprises two giant sculptures, installed (until June of 2022) on opposite sides of the blue room in De Singel in Antwerp.

Now that more and more sound art is being produced and is finding its place in exhibitions and in the artistic operations of art institutions, one question for the future concerns its conservation. How do we preserve sound art and how do we archive its progress? One concern is specific knowledge of the media involved, which is not universally available.

In museum collections, sound art is today still underrepresented, but here too, interest is growing. In 2021, for example, M HKA purchased artist Maika Garnica’s sculptural installation with ceramic sound objects, entitled From Bow to Ear, as part of the City of Antwerp’s municipal collection. In this sound work, five arch structures delineate the space and support an array of ceramic instruments. At specific times, this performative installation is activated by the artist, whose touching and handling of the objects resonates through the space by way of contact microphones.

Museum Z33 has recently launched In Echo, a podcast about the relationship between art, its makers and sound. The S.M.A.K. collection also includes a number of sound art works by primarily visual artists, including 166 Betten – Peace and Noise, completed in 1998 by Susanne Tunn. The work is made up of 166 unyielding beds that can be ‘as silent as the grave’ while still radiating a strange music. Installed in a church, these beds are perhaps ready to be laid underground, in burial vaults, in a contemporary evocation of anonymous, mass death caused by political and social unrest.

Today, sound art is a medium that receives little subsidized support, the result of which is that many sound art projects are in the context of research and associated with limited time spans. Self-reflection and assessment within the medium, from a local perspective as well as within the international framework, is therefore still in its infancy.

There is a shortage of studio spaces, and artists and organizations are experiencing a growing need to organize and exchange experiences, feedback and processes in both formal and informal frameworks (for example, in comparison with the theatre world).

We are trying to show content from Vimeo.

Kunsten.be only uses minimal cookies. To view content by a third party website, this site can place additional cookies. By continuing to browse you are agreeing to the use of those third party cookies.

Read more about our privacy policy?

People are becoming acquainted with sound art by way of various higher education institutions, for example in the studios of Esther Venrooy and others at the Sint Lucas campuses in Ghent and Brussels, and the radio course with Jeroen Vandesande and Johan Vandermaelen and others at RITCS School of Arts. In addition, KASK School of Arts in Ghent offers the EPAS study programme of European graduate courses for sound within the arts, founded by researcher Martine Huvenne, although there is no complete master degree programme available. This means that as a field of study, sound art is fragmented and is developing heterogeneously.

Various organizations have been developing trajectories for pre-professional and newly graduated artists in order to help guide them on their way to a professional art practice. We can also note here that there are as yet almost no organizations devoted to the management and/or sale of sound art, something that could be helpful for young artists.

Finally, the landscape in Flanders and Brussels is increasingly connected with organizations in both French and German speaking communities, such as Meakusma, for example, and are engaging in more and more long-term collaborative European projects.

Footnotes

[1] According to researcher and curator Linnea Semmerling (IMAI – Inter-media Art Institute, Düsseldorf), sound art can be understood as ‘an artistic practice whereby sound is used as a medium, which is conceptually devoted to sound or whereby sound or ideas about sound are presented in a way that goes against traditional presentation in a concert hall.’ From L. Semmerling, ‘Sing a Song: gedurfde geluidskunst’, in Metropolis M, No.5, 2017.

[2] Steve Goodman, Sonic Warfare, Sound, Affect, and the Ecology of Fear, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2010

[3] Laura Maes, Marc Leman, ‘Defining Sound Art’, in The Routledge Companion to Sounding Art, Routledge, New York, 2017, pp. 27-41; and Laura Maes, Sounding Sound Art: A Study of the Definition, Origin, Context, and Techniques of Sound Art, PhD dissertation in musicology at the University of Ghent, under Marc Leman and Godfried-Willem Raes

[4] ibid., ‘Defining Sound Art’, pp. 27-41

[5] Based on a quote by composer Morton Feldman

[6] With visual artists Arnaud Eeckhout and Mauro Vitturini

[7] Linnea Semmerling, ‘Luisteren na Pauline, De Missie van Deep Listening’, in Metropolis M, No. 1, 2020, p. 60

[8] This article provides only a brief introduction to the history of sound art. More information can be found in Alan Licht, Sound Art: Beyond Music, Between Categories, Rizzoli International Publications, New York, 2007, and Douglas Kahn, Noise, Water, Meat: A History of Sound in the Arts, 1999, MIT Press, Cambridge MA, USA

[9] MATRIX Componistenfiche Karel Goeyvaerts, consulted on 14 May 2022

[10] The archives of composer Louis De Meester include a treasure trove of non-digitized tapes of field recordings that served as musical material and/or inspiration for his artistic practice.

[11] Baudouin Oosterlynck, ‘From Solitude to Accompanied Monody’, in Documenta Belgicae, vol. II: Music, Archennes, PMA-Co-editions, 1985, pp.134-154

[12] Following INA GRM in Paris

[13] A European collaboration between Stichting Intro/In Situ (Maastricht, NL), Le Bon Acceuil (Rennes, FR), Lydgalleriet (Bergen, NO) and Festival of Flanders, Kortrijk. Audio Art Festival (Krakow, PO) and Skanu Mezs (Riga, LV) are associated partners.

[14] Linnea Semmerling, ‘Transformations of the Audible: Rehearsing Sensory Repertoires’, online lecture held at West Den Haag, Institute of Sonology (Royal Conservatory of The Hague) and the University of Leiden, 2019

[15] The Sounds of Europe project focusses attention on the recent expansion of field recording in music, art and science. It was launched by Q-O2 in collaboration with MTG (Music Technology Group/University of Barcelona) / Sons de Barcelona, IRZU (Institute for Research in Ljubljana) and CRISAP (Creative Research in Sound Arts Practice, University of London).

[16] SoCCoS (Sound of Culture – Culture of Sound) is a network of residencies and research in exploratory music, sound art and sound culture. It creates residence opportunities with exchanges between artists, cultural workers and theorists. In collaboration with Hai Art (FI), Binaural/Nodar(PT), DISK Berlin (DE), A-I-R Laboratory (PL) and Q-O2 (BE). Associated partners are Bambun (IT), MoKS (EE), Kumaria/Medea Electronique (EL) and De School van Gaasbeek (BE).

[17] In partnership with Intro In Situ (Maastricht, NL), bb15 (Linz, AT) and Lydgalleriet (Bergen, NO)

[18] An organization founded by Lilith Geeraerts & Anna Van Hoof, providing Brussels with a quiet, stimulus-free space and promoting awareness of the importance of silence

[19] A European collaboration under the leadership of the City of Roeselare, together with the Idensitat organization in Barcelona

[20] Onassis Stegi (GR), Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival (UK), Ultima Oslo Contemporary Music Festival (NO), November Music (NL), SPOR Festival (DE), Time of Music (FI), Transit Festival – Festival 2021 (BE), Wilde Westen (BE)

[21] Brandon LaBelle, Radio Territories, Errant Bodies Press, Berlin, 2007

[22] Klankverbond aims to unite and defend all those who do ‘something with audio’. They are located in the Passa Porta complex in Brussels.

Bibliography

A. Engström, A. Stjerna, Sound Art or Klangkunst? A reading of the German and English literature on sound art.

A. Licht, Sound Art: Beyond Music, Between Categories, 2007, Rizzoli International Publications, New York.

B. LaBelle, S. Roden (eds.), Site of Sound: Of architecture and the ear. Los Angeles, Errant Bodies Press/Smart Art Press, 1999.

B. LaBelle, Radio Territories, Errant Bodies Press, Berlin, 2007.

C. Bishop, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship, Verso, Brooklyn, 2012.

C. Claus, Studio_L28 – Sonic Perspectives on Urbanism, Umland, Brussel, 2018.

C. Lane, A. Carlyle, In the field, Uniform Books, 2013.

D. Kahn, Noise Water Meat: A history of sound in the arts. Cambridge, MIT Press, 1999.

E. Coussens, Hoor, de paprika ontkiemt: een interview met Stijn Dickel van aifoon, aifoon.org, 2020. Laatst geraadpleegd op 02.05.2022.

E. Venrooy, On the Process of Becoming Silent and Listening, 2015.

E. Venrooy, Audio Topography-on the Interaction of Sound, Space and Medium, LUCA/KULeuven, 2013.

F. Blume, Doors of Listening, Pelt, 2021.

H. Andersen, C. Profanter, J. Eckhardt (eds.), The Middle Matter, Sound as Interstice, Umland, Brussel, 2019.

I. Devriendt, Stroomopwaarts: Maika Garnica – Gevoelsmatig communiceren, in: OKV, 2021.

J. Croonen, Geluidskunst, Berlijn in het Leuvense stadspark, In: De Standaard, 22 april 2021.

J. Eckhardt, Grounds For Possible Music, Umland, Brussel, 2018/

L. Maes, M. Leman, Defining Sound Art, In: The Routledge Companion to Sounding Art, Routledge, New York, 2017, pp. 27-41.

L. Semmerling, Sing a Song: gedurfde geluidskunst, in: Metropolis M, No.5, 2017.

L. Semmerling, Luisteren na Pauline, De Missie van Deep Listening, in: Metropolis M, No. 1, 2020.

L. Semmerling, Transformations of the Audible: Rehearsing Sensory Repertoires, online lezing gepresenteerd door West Den Haag, Institute of Sonology (Koninklijk conservatorium Den Haag) en de Universiteit van Leiden, 2019. Laatst geraadpleegd op 02.05.2022.

M. Delaere, Een Kleine Muziekgeschiedenis van Hier en Nu, Pelckmans Pro, Kalmthout, 2020.

M. Delaere, R. Diependaele, V Verspeurt, Contemporary Music in Flanders: Tape music since 1950, Matrix, Leuven, 2010.

M. Chion, Sound: An Acoulogical Treatise, vertaald door James Steintrager. Durham: Duke University Press, 2016.

M.P. Wright, Listening After Nature: Field Recording, Ecology, Critical Practice, Bloomsbury, New York, 2022.

S. Goodman, Sonic Warfare, Sound, Affect, and the Ecology of Fear, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2010.

S. Janssen, M. Seuntjens, De Methode, hoe die soms is, misschien was of zou kunnen zijn, Brussel, 2017.

Interviews with: Floris Vanhoof, Amber Meulenijzer, Jan De Moor, Gilles Helsen, Esther Venrooy, Julia Eckhardt, Matteo Marangoni, Guy Van Belle and Iris Paschalidis

Thanks to Ward Bosmans, Christoph Deboeck, Jan De Moor, Dirk De Wit, Julia Eckhardt, Gilles Helsen, Martine Huvenne, Aernoudt Jacobs, Sarah Rombouts, Esther Ursem, Jannis Van de Sande, Frederic Van De Velde