Let me be your guide: Media art in Flanders, a hybrid history of its origins

Faces of water (c) Caroline Lessire

Ranging from art with analogue video and sound techniques to the first computer art, from CD-ROMs to interactive websites and games, the output of media art consists of infinite variations on audiovisual installations, virtual artworks and multimedia performances.

Furthermore, media art is as changeable as the technologies – analogue or digital, hardware or software, algorithms or robotics – that it uses as its subject, material and medium.

Cross-over, bottom-up and artist-run

This text offers a brief overview of the history of media arts in Belgium. It is striking that the origins of this form are as hybrid as its output. Media art developed from different disciplines: early video art, experimental music and the performing arts.

Early media artists were genuine pioneers when it came to connecting artistic research with fields outside the world of art. For example, they often worked intensively with research or media labs at universities, or with innovative companies developing a specific technology.

Although this crossover mentality may be considered one of its greatest strengths today, the situation has emerged in Flanders somewhat in spite of itself. Because it has reinvented itself time and time again, changing its materials and techniques ever more quickly, media art has struggled to gain a foothold in the traditional art world.

The new ways of experiencing art forms that it helped to usher in – such as interactivity, participation, immersion and intermediality – were also beyond the usual frame of reference of large institutions, audiences and art critics.

In Flanders, media art is a still young and dynamic sector that works at close proximity to its artists, with little institutionalisation and plenty of space for innovation and experimentation.

For a long time, museums ignored these changeable, temporary art forms. There is still a major gap, even today, when it comes to their presence in museums and collections. That is not just because of the material: above all it is due to the speed at which some technological formats (such as CD-ROMs, video tapes, websites, certain robotics or software) keep changing and ageing.Conservation of media art is therefore an ongoing task. “In just 50 years, we are already in the phase of needing to reconstruct works that have disappeared. And this loss, this appearance and disappearance, is actually also inherent to the ambitions of new media.” (David Claerbout)

In terms of financial support, the government offered little until the 2000s. It evaded the issue with a mostly administrative debate: should these new art forms be accommodated in the field of the arts, or covered by the film fund that existed at the time (that later became the Flemish Audiovisual Fund, or VAF)?

It was not until the early 2000s that the government took the initiative of officially recognising media art as an art form. From that point onwards, video artists were covered by the VAF. Artists and organisations working in new media were supported by the Kunstendecreet (arts decree), categorised variously under the Audiovisual Arts, Residences, Performing Arts or Music. Since then, there has been an increase in the number of organisations and artists and steadily increasing professionalisation.

Today, the VAF supports single-screen video work and gaming, whereas visual media art and sound art constitute a subgenre of Visual Arts named ‘Experimental Media Arts’. Simultaneously, many new media artists and organisations are classified as belonging to the Performing Arts (CREW) or Music (ChampdAction, Stefan Prins or Aurélie Lierman).

We are trying to show content from YouTube.

Kunsten.be only uses minimal cookies. To view content by a third party website, this site can place additional cookies. By continuing to browse you are agreeing to the use of those third party cookies.

Read more about our privacy policy?

An intricate web of highly diverse production and development-oriented organisations has emerged from the hybrid background of media art, each with its own expertise and approach. Many of these are run by artists, for artists and have emerged from the bottom up, arising both from the need for a production context and access to facilities and from a practical need to bring expertise together and create networks.

As a result, compared to other sectors today in Flanders, this subsector is still young and dynamic, as well as being close to the artists. It knows little institutionalisation and offers plenty of space for innovation and experimentation.

At the same time, media art is also much more fragile than more traditional art forms precisely because it does not have an underlying institutional network of large venues, festivals or institutions that help to support the artists and distribute their work.

Players in the Flemish media arts

The rocky road of video art

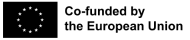

In Flanders, it was not until the early 1970s that video art gradually began to appear in an increasingly diverse arts scene. Under the artistic director at the time, Flor Bex, the first video production studio, Continental Video, was set up in the ICC in Antwerp in 1972.

It enabled artists like Leo Copers, Danny Matthys, Guy Mees, Lili Dujourie (and later Jan Vromman and Stefaan Decostere) to start experimenting with video. Many Walloon artists, such as Jacques Charlier, Jacques-Louis Nyst and Jacques Lizène, also came to produce work at the studio. However, its activities fizzled out after several years, leaving an empty space behind.

This is in contrast to Wallonia, where video art was able to continue developing actively under the influence of certain powerful figures (such as Jean-Paul Tréfois). Thanks to the alternative radio and television channels, they had access to production facilities. Furthermore, their work was shown in a small but specialised screening circuit that included the famous Vidéographies on the RTBF state television broadcaster, Yellow Galerie in Liège and a few smaller festivals (including one at the Botanique).

In Flanders, there were only a handful of venues or galleries that paid attention to experimental video art, such as Wide White Space or the multidisciplinary art space Montevideo (run by Annie Gentils, among others). Besides video art, other early forms of media art also found a home there.

In 1981, for example, Montevideo’s opening exhibition consisted of an interactive spatial installation with sound and light beams by the artist Luc Steels, the man who founded the Artificial Intelligence Lab at the VUB a few years later.

In 1981, Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven and Danny Devos founded their famous Club Moral, the Antwerp underground venue that combined noise and punk performances, performance, video, film screenings and electronic art.

As the name suggests, Club Moral was interested in ethical issues in art, science and society, without pronouncing a moral judgment of its own. The focus was on an unbiased exhibition and revelation of the underlying codes of mass media, resulting in a mix of punk, trash propaganda and eroticism.

After a turbulent period at Club Moral, Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven began to explore digital media and artificial intelligence in increasing depth, focusing more on the development of websites and computer animations. In her iconic work Headnurse, for example, she explored her fascination and disgust with the female body in visual culture by means of digital computer animations that she unleashed on the internet as a ‘healing’ force.

In the art academies of Ghent and Brussels, meanwhile, a new generation of video makers (and young teachers and critics such as Chris Dercon) had also emerged, who were broadening the traditional vision of audiovisual art as ‘film’ and championing video art as an autonomous genre.

Like Van Kerckhoven, they were fascinated by the raw, radical and absurd aesthetics of the material. Figures such as Frank and Koen Theys, Dirk Paesmans, Jos de Gruyter and Harald Thys caused an international furore with innovative experimental video work, despite an embarrassing lack of recognition at home in Flanders. Due to the lack of production facilities, they founded De Nieuwe Workshop under their own steam, run by the experimental filmmaker and teacher at Sint-Lucas, Frank Vranckx.

It was almost the only place in Flanders at the time where video artists had access to production facilities (besides the audiovisual department at the KU Leuven, which turned a blind eye to artists using the studio when it was not in use). This collaboration was later continued by ‘t Stuc, one of the few places in Flanders that presented media art to an audience during that period, for example under the impulse of its programmer at the time, Dirk De Wit.

The role of university media labs

While KU Leuven’s audiovisual studio was an important production site for video art, two other media labs played an important role in the early development of other forms of media art.

In 1983, for example, the Artificial Intelligence Laboratory was founded at the VUB by the scientist and artist Luc Steels, who gained international renown for his pioneering research into AI. The lab collaborated with countless artists on the development of new techniques in coding, machine learning and robotics.

Another pioneer from Flanders who was linked to this lab is Peter Beyls, who has been working with computer art since the 1970s as a scientist and digital artist. He gained worldwide recognition for his research and experiments with interactive music and generative art.

He used feedback processes from algorithms to explore the imaginary possibilities of software. Since the 1990s, he has also been actively involved in ISEA (Inter-Society for the Electronic Arts), one of the most important international media festivals.

Previously, Beyls had worked at another important research lab, the IPEM (Institute for Psychoacoustics and Electronic Music), where he did revolutionary work with electronic and interactive music.

The IPEM was founded in 1963 as a collaboration between the BRT – the Belgian national broadcaster at the time – and Ghent University. The institute had a twofold mission: firstly, it was to produce radio and television productions, and secondly, it conducted innovative research into sound technology and electronic music.

Led by legendary composers such as Lucien Goethals, Karel Goeyvaerts and Louis De Meester, the IPEM grew internationally into a unique production studio where composers and artists could familiarise themselves with the latest technologies in the field of electronic music.

The BRT stopped using the lab for production in 1987, and it was converted entirely into a university research lab. For a long time, the IPEM was one of the only places in Belgium for a long time where sound artists could produce and develop their work.

Later on, the IPEM also experimented with new technologies such as virtual and augmented reality, biofeedback, interaction, immersion, 3D sound rendering and motion tracking. Today, the IPEM – and more specifically its Art-Science-Interaction Lab (ASIL) led by Guy Van Belle – is still an important place where art, technology and science meet. In 2019 there were collaborations with the artists Anouk De Clercq, Ruben Bellinkx, Jürgen De Blonde/Köhn, CREW and many others.

The flight to multimedia theatre

In the late 1980s, there was hardly anything left in terms of production facilities except for the production labs at Ghent and Leuven universities. Moreover, it was becoming steadily more expensive to lease commercial spaces and equipment. In Brussels, De Beursschouwburg had absorbed De Nieuwe Workshop and soon given up on it again.

The aftermath of this rather unpleasant history would lead to the creation of Argos a few years later, which is now considered to be one of the most important players in the distribution of video art in Belgium.

All the same, several artists from that period (including Walter Verdin, Peter Missotten, Cel Crabeels, Frank & Koen Theys and Jan Vromman) managed to scale international heights with their work, despite being almost unknown on the Flemish arts scene. Many media artists had to go abroad to be able to create their work. There was still no progress in terms of recognition and support from the government.

In the 1990s, many Flemish video artists sought refuge in the performing arts, where they found funding, recognition and an international professional network.

The early 1990s brought little improvement. Abroad, media art was gaining increasing autonomy and major media festivals were founded such as Ars Electronica, Transmediale, Impakt and the Electronic Arts Festival. In Flanders however, there was still barely any interest for the experimental media arts.

One of the consequences was that Flemish video artists started to seek refuge in other disciplines such as the performing arts. Not only did they receive funding and recognition there: it also offered them a professional and international network that created opportunities to experiment extensively with new audiovisual technologies.

The work made during this period by Walter Verdin, Frank Theys and Peter Missotten (with De Filmfabriek) was key to the proliferation of multimedia in the performing arts, with countless successful collaborations with Rosas, Wim Vandekeybus, Guy Cassiers and An Quireinen, among others.

It was not until the late 1990s that media art began to develop increasingly into an autonomous genre in music and the visual arts as well as the performing arts. An example of this is the evolution of CREW, led by Eric Joris.

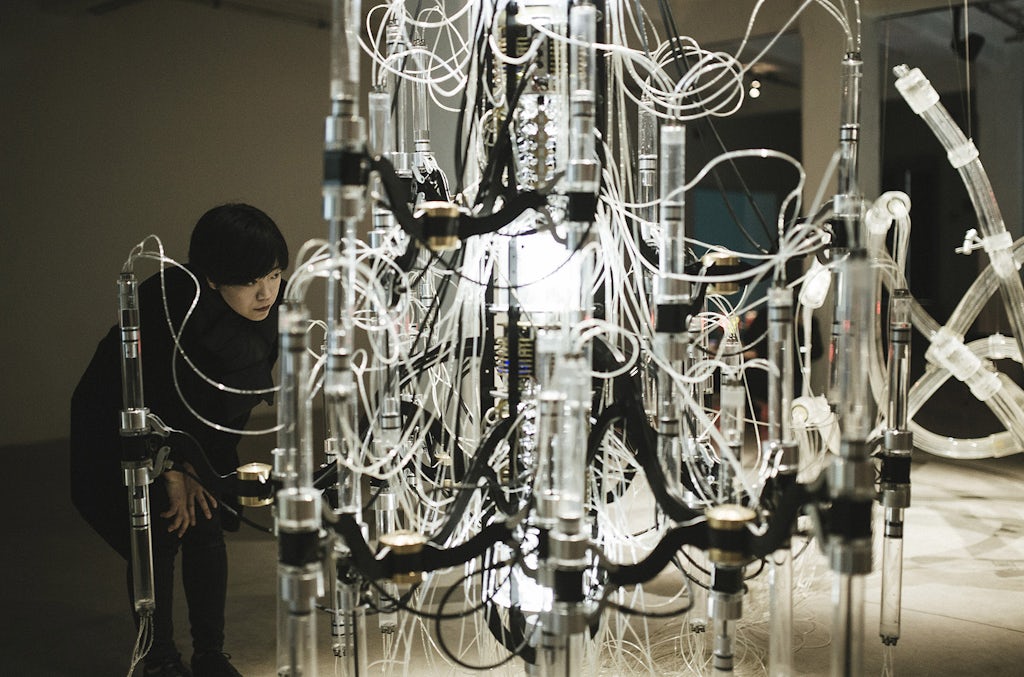

Founded in 1991 with a background in theatre, this collective of artists, technicians and scientists began to focus entirely on the creation of high-tech live art in the 2000s. CREW creates impressive, immersive productions focusing on fully embodied experience as well as visual perception.

The collective was among the first to experiment with VR, 3D and 360° technology and motion sensors, which resulted in iconic works such as Crash, C.A.P.E., W_Headswap, Terra Nova and Eux, all of which featured in major festivals around the world. They use technology to get the spectators moving, often literally, inside a spatial environment where the boundaries between the real and the virtual are fragmented.

We are trying to show content from Vimeo.

Kunsten.be only uses minimal cookies. To view content by a third party website, this site can place additional cookies. By continuing to browse you are agreeing to the use of those third party cookies.

Read more about our privacy policy?

Lawrence Malstaf – who started out as a theatre set designer – also began to explore crossovers between live performance and spatial installations. In his iconic work Nevel, the visitor walks through a labyrinth of responsive walls that constantly change the space, creating a new horizon time and again.

Both Malstaf and CREW have since grown into international benchmarks in the field of live performances with robotics, interactivity and exploring the boundaries between humans and machines.

Two artists who were active at De Filmfabriek, Ief Spincemaille and Kurt d’Haeseleer, have focused increasingly on media art as an autonomous practice since Peter Missotten’s departure. A fascination with the interaction between new technologies and visual culture led to the creation of artist-run organisation Werktank.

It has become one of the first workplaces where media artists from Belgium and elsewhere can work on productions and develop audiovisual installations or multimedia performances with electronics, computers, VR or robotics.

The focus is on providing production support, in terms of both resources and expertise in creating work, and obviously also on creating a network of like-minded artists, with a mixture of domestic and international residents. Artists such as Floris Vanhoof, Els Viaene, Elias Heuninck and Wim Janssen have all been based there.

Net-based art, the world wide web

Meanwhile, increasing access to computers and the rise of the world wide web injected new energy into the media arts. Like Van Kerckhoven, some other artists who had been experimenting with video in the 1980s became increasingly fascinated by the impact of the internet.

Koen Theys made iconic works from the 1990s onwards that explore the world of homemade YouTube videos: in The Final Countdown he brought together hundreds of films of people performing their own versions of Europe’s hit song. A similar video installation, Danaë, shows a constellation of amateur films by anonymous teenage girls doing a booty shake in front of the webcam.

Dirk Paesmans left video as a medium to form the collective jodi with the Dutch artist Joan Heemskerk. The collective is one of the absolute pioneers of internet art. Just two years after the internet became available to a wider audience, they travelled to Silicon Valley and created their first websites, on which they made the underlying code of the internet visible rather than the top layer.

These radical works included websites that crashed themselves, e-mail chains, hacks, games and viruses. They turned the gaze of the steadily growing world of internet users towards the invisible and sometimes murky infrastructures hidden behind the promised utopia of the internet. It was not unusual for their work to create a stir or even a form of minor panic.

The same radical attitude can be found in the early internet work of Michaël Samyn, who appeared under the name Group Z as a collective of avatars of the artist and created several iconic internet works such as LOVE and I Confess. Together with Auriea Harvey, Samyn continued his work in the collaborative project Entropy8Zuper! In the 2000s, the duo began to focus increasingly on the development of games.

Their project Tale of Tales used immersive and interactive methods to develop artistic games. One of their most famous works is the multiplayer game The Endless Forest (started in 2006 and still running), in which the players are encouraged to explore their surroundings and discover other players.

The games they develop as Tale of Tales are a departure from the typical gaming experience centred on entertainment and action; they are resolutely committed to the imaginative potential that the virtual, interactive and non-linear world of gaming has to offer.

We are trying to show content from Vimeo.

Kunsten.be only uses minimal cookies. To view content by a third party website, this site can place additional cookies. By continuing to browse you are agreeing to the use of those third party cookies.

Read more about our privacy policy?

The work of jodi and Entropy8Zuper! was intensely networked internationally in the mid-1990s in a somewhat small and obscure circuit of activist net artists. Like the video circuit of the early 1980s, internet art was a way to move away from the traditional, intellectual art world.

Internet art created its own alternative visual language inspired by popular culture, games, advertising and daily life. It also operated in its own circuit of mailing lists, online galleries and web platforms (äda’web, irational.org, DIA, rhizome.org, bitforms) where work was shared with great enthusiasm, to a small group of insiders.

At the point when the institutional art world began to discover internet art and major museums such as MOMA started buying works by jodi or organising large exhibitions on software and internet art, internet art declared itself dead.

Media activism

Although this initial form of ‘internet art’ may have officially ceased to exist, and moreover only had a somewhat limited output in Belgium, an increasingly lively circuit based on digital culture emerged in Brussels in the late 1990s.

Some of these initiatives rode the wave of the internet and emerged from an overlap with the creative industry. In Brussels, for example, the CyberTheater was founded by the internet company Nirva-Net, which stimulated innovation in digital media and also actively sought out projects that overlapped with net art and media art.

Nirva-Net ran the CyberTheater in an old cinema in Brussels, a unique space where the world of media art crossed paths with the dotcom world and dance music. It experimented intensively with the very first live streaming events, augmented reality and 3D. At the same time, it was an internet café during the daytime and held DJ nights and conferences for a new, hip generation of digital entrepreneurs.

In Ghent, the non-profit organisation nMn (short for naarstige Media nijverheid, or intense Media industry) organised Dorkbot evenings at the Nieuwpoorttheater. Like CyberTheatre, Dorkbot concentrated on informal meetings between like-minded people involved in all kinds of new media. Attendees at Dorkbot evenings could have a drink at the bar and enjoy a performance, concert or lecture.

Dorkbot tried to offer a platform to as many new media artists as possible. It did not present a curated programme; instead it encouraged encounters between like minded peers and was based on the idea of sharing and discussing each other’s work. Incidentally the organiser, Jan De Pauw, had previously worked at the CyberTheater as well. The Ghent Dorkbot evenings were connected to a larger international network of Dorkbot events.

Around the same period –the late 1990s – the media artist Yves Bernard founded iMAL (Interactive Media Art Laboratory), a production site and centre of expertise for media artists in Brussels. During the heyday of CD-ROM culture, Bernard ran the production company Magic Media, which not only produced CD-ROMs for the commercial sector, but also frequently collaborated with artists.

Today, iMAL has become one of the most important showcases for media art in Belgium. In addition to its activities as a workshop, it has built up a programme of activities that makes media art more accessible to a wider audience through exhibitions, lectures, workshops and performances.

More and more artists, collectives and organisations gradually started to devote their attention to digital network culture as the basis for an artistic media activism practice. Some of these organisations grew into established names in the media landscape: Constant, FoAM, iMAL, OKNO and Nadine.

This highly networked group of organisations became home to a wide range of media artists: Annemie Maes, Nathalie Hunter, Femke Snelting, Peter Westenberg, Wendy Van Wynsberghe, Guy Van Belle, Thomas Soetens and so on.

They explored the transgressive potentials of code and algorithms, free software, open publishing, games, hacking, cyberfeminism, DIY technology and ecology. Together, they significantly boosted the growth of media art in Belgium.

Furthermore, several collectives emerged that were more interested in exploring technology in relation to the experience of architecture, space and the urban environment, such as Workspace Unlimited and LAb[au].

These were all organisations with hybrid, flexible activities that ranged from workshops, residences, festivals and productions to research activities. They focused on critical thinking about technology combined with ‘making’, allowing for all kinds of radical experimentation and diversity.

An explosion of festivals

In the screening circuit, a lot started to happen in the early 2000s. This had everything to do with growing recognition and funding from the subsidising authorities, who began to see the experimental audiovisual arts in a broader light than just video art at that point.

From 2001 to 2005, Argos organised the annual Argosfestival, which created an important stimulus for makers of experimental media art, the ever-growing group of video artists and all the crossovers that arose between the two.

Inspired by director Paul Willemse and programmer Ive Stevenheydens, the Argosfestival explicitly sought out the boundaries between art, film and experimental music. There was space for multimedia installations, computer-based arts, electronic music, sound art and conferences on the theory of media art. The festival was not only held at Argos, but also in alternative cinemas such as Cinema Nova and alternative music venues such as Recyclart or AB Club.

As the number of venues increased, the Argosfestival also managed to introduce media art to a more diverse audience. It also created an important new link with the underground club scene of DJs, turntablism and video mixing.

This angle was expanded into an all-round approach by the Cimatics Festival in Brussels, first held in 2003. It was one of the first festivals in Europe to explicitly commit to the crossover between experimental media art and the new subcultures in electronic music (there was a vibrant club scene for electro, techno and drum and bass in Belgium at the time). This festival also invariably looked for alternative venues to maintain a very active relationship with the city: from Recyclart and technoclub Fuse to the Atomium and planetarium.

Like the Argosfestival, Cimatics provided an important stimulus: both festivals brought international artists, producers, distributors and programmers together, making Brussels part of a lively international circuit.

One of the darlings of Cimatics, for example, was Ryochi Kurokawa. His work rheo: 5horizon, produced by Cimatics, won the famous Ars Electronica Golden Nica prize in 2010.

We are trying to show content from Vimeo.

Kunsten.be only uses minimal cookies. To view content by a third party website, this site can place additional cookies. By continuing to browse you are agreeing to the use of those third party cookies.

Read more about our privacy policy?

As media art gained increasing recognition and attention, a lively scene emerged in cities such as Brussels, Leuven and Ghent. Various other festivals saw the light of day, such as Almost Cinema, hosted at Vooruit during Filmfestival Gent, Courtisane (also in Ghent) and Contour in Mechelen.

Each of these festivals provided a platform for all kinds of hybrid media art forms, ranging from expanded cinema to sound art, digital art, multimedia installations and performances.

STUK in Leuven, which has paid explicit attention to media art from the outset, started the Artefact Festival in 2003. What set it apart from other festivals was its resolute choice of an exhibition context. In addition to live performances, it hosted multimedia installations and more spatial works.

Thus Artefact grew into the ideal place for visual artists who worked with technology. For example, the work of Angelo Vermeulen, Kurt Vanhoutte, Ief Spincemaille and Lawrence Malstaf was presented here alongside the cream of international media artists.

From experimental music to sound art

Important pioneers included Peter Beyls and Guy Van Belle, who worked at the IPEM. And although he is something of an outsider in the arts circuit, the role of Godfried-Willem Raes and his organisation Logos is also worth mentioning.

Logos conducted idiosyncratic but pioneering experiments with music and robotics, resulting for example in interactive brass bands. Other than the internationally renowned IPEM studios, however, there were few facilities for sound artists or opportunities to present their work.

An important boost in this area came from the music programmer Joost Fonteyne. He organised the Happy New Ears festival from his home city of Kortrijk, programming all kinds of avant-garde music from electronic music to improvisation and free jazz and – since 2002 – sound art as well.

The sound art programme continued to evolve into Klinkende Stad, a trail of sound-based artworks in public spaces, using that context to explicitly seek dialogue with the wider audience of the city, its inhabitants and many visitors. The festival also offered support to new creations.

While Fonteyne has since left the Kortrijk circuit to become director of the Klarafestival, his role has been taken over by the Wilde Westen. That organisation has set its sights on crossovers between alternative and experimental music, jazz and sound art; among other things, it organises the multidisciplinary festival Het Bos.

In West Flanders, Concertgebouw Brugge has also started actively commissioning sound artists to create work in the building since the renovation. Under the name the Sound Factory, it aims to work with the museums in Bruges to give interactive sound art a permanent place in Bruges and the Flemish cultural landscape.

On the other side of the country, in Neerpelt, Musica has been increasingly exploring the boundaries between classical, traditional forms of music and sound art and experiments with sound. In its woodland surroundings, Musica has created a unique open-air museum for sound art: Het Klankenbos.

It is a place where a wide audience can encounter sound works created in situ by international artists in an accessible way that makes listeners aware of both sound and silence. New acquisitions are regularly added to the Klankenbos collection.

In addition, Musica is also very strongly committed to education in the field of sound, music and listening, and offers an extensive educational programme for people of all ages in addition to its residences, production support and workshops for artists.

Another player in sound art that emphasises participation is aifoon, which started out in 2003 as an arts education organisation focusing on field recordings. In recent years, however, aifoon has reinvented itself as a participatory arts organisation centred on research and development in ‘the art of listening’.

aifoon works with interdisciplinary partners from the arts world and elsewhere (education, heritage, healthcare, urban planning etc.). Its projects focus on the movement involved in listening. According to the artistic director Stijn Dickel, “listening art is not focused on sound, but on the experience and interaction between the body, space, sound and movement.”

Just as with the history of more visually oriented media art, we see here that – despite growing interest from programmers and audiences – creators have had a hard time producing their work. Many organisations and artists are organised from the bottom up.

The experimental music ensemble ChampdAction, which was founded in the late 1980s and has been home to artists such as Stefan Prins and Serge Verstockt, is now actively using its years of accumulated expertise in music and technology to support makers, profiling itself as a space for residence and development.

In Brussels, the music ensemble Q-O2 has also metamorphosised into a workspace, organising residencies focused on reflection, development and research in the field of sound and music since 2003. In addition to its residency work, Q-O2 also organises symposiums and festivals (such as the Oscillation Festival) and runs a publishing house (umland) that focuses specifically on spreading knowledge about sound art.

Overtoon has also emerged from the shared interest of two makers (Aernoudt Jacobs and Christoph De Boeck) as well as from the pressing need for production facilities and networks. Unlike the workspaces above, Overtoon explicitly aims to commit to visual media art and provide a platform for the growing segment of sound artists.

Overtoon focuses on the more physical and material side of sound art and is fully committed to the production of high-quality audiovisual installations. Many contemporary Flemish sound artists (Gert Aertsen, Jeroen Vandesande, Jeroen Van Uyttendaele) have found expertise, support and an international network at Overtoon.

New, Media, Art and Technology

Today we can see that the definition of media art is being broadened further and further beyond its strict link with ‘media’ or ‘new media’ and is interpreted more in terms of the interaction between art, science and technology.

Take internationally recognised artists such as Nick Ervinck, who combines innovations from the world of 3D printing and scanning with his practice as a sculptor. Or Koen Van Mechelen, Frederik De Wilde and Angelo Vermeulen, artists who have gained international fame through their experiments with biology, astronautics or nanotechnology.

They use the same processes as the ‘old’ new media artists, and make art by dissecting, reprogramming or hacking code. They use technology as a fundamental element of an artistic creation process.

Christophe De Jaegher, the curator of media art at Bozarlab, set up Gluon a few years ago, his own organisation that is one of the first in Flanders to focus very explicitly on the interaction between art, technology and science.

Gluon puts artists in touch with scientists or companies and vice versa, organises residency projects and provides production support for projects with an explicit focus on the cross-pollination between these different fields of activity.

A second important pillar of the organisation is the link to education. Besides workshops that focus on increasing media literacy and critical thinking on topics such as data mining, AI or gene technology, Gluon organises hands-on workshops at which young people and schools get to grips with the many creative possibilities of the digital tools available today.

iMAL also appears to embrace this broadening, and has devoted various projects to bio-art or other links to science. In 2020, it opened its renovated exhibition space with an exhibition derived from the collaboration between CERN scientists and international artists, in which Gluon also acts as a partner..

Bozarlab focuses on digital media and technology in the broad sense. In addition to organising the annual Electronic Arts Festival, it has also been a partner in the European STARTS programme for several years now, a prestigious exchange project between art, technology and science.

Building on the growing connections between art and science, KULeuven also set up a new residence in 2019. The BAC ART LAB focuses on artistic practices at the intersection of art, research and education.

Likewise at an international level, we see that the big festivals such as Transmediale, ISEA, STRP, Sonic Acts or Ars Electronica are increasingly broadening their approach. They no longer refer to themselves as festivals for media art, but focus on the relationship between art, media, technology, science, ecology and society, actively fostering crossovers with creative industry, non-profit organisations and universities. Innovative start-ups are programmed alongside hackers, ngo’s, academics and artists.

With this momentum behind it, the presentation of media art in Belgium has also shifted towards broader festivals on digital innovation, such as the KIKK in Namur or the new AND festival in Leuven. Following the example of STRP festival in Eindhoven, the later concentrates explicitly on the crossover between innovation, science and art.

In collaboration with the VRT (Flemish radio and television broadcaster), the Flemish government has also set up a new festival for digital innovation, renamed Media & Culture Fast Forward this year. But there is no really big international player at the moment, which is a disadvantage for the many production centres and artists who rely on their own resources and foreign institutions to distribute their work.

Media art stimulates media literacy as well as innovation– something absolutely essential in a world of digital natives – and makes us stop and think about ethical issues that are too often brushed aside by commercial media.

The importance of the role of media art has only heightened as the digital and artificial are increasingly overlapping with the physical and natural world. Media art stimulates media literacy as well as innovation– something absolutely essential in a world of digital natives.

Media artists force us to stop and think about ethical issues that commercial media too easily brush aside, such as surveillance and privacy, forms of exclusion and stereotyping, ambiguity or disinformation. They also address the ethical questions raised by developments in life science and gene science, crispr or AI.

The general thread running through this hybrid history then is not the technology itself, but the way in which artists critically dissect the materials, codes and language of technology. The interaction between art and technology not only encourages the viewer (or user) to consider it with a critical eye, but also ensures innovative practices and leads to the development of alternative ideas and applications.

Media artists research, programme and hack the hardware and software that is so ubiquitous in our society today. Knowledge, tools and skills are shared with the rest of their community and with the world by means of open hardware, free software or free license publishing platforms.

Media art is also in the vanguard of an alternative digital society, a network where openness, sharing and free access to knowledge and expertise are central and where new alliances are sought between technology and society.

In this way, media art separates technology from its purely functional or commercial purposes. Rooted in an artistic practice, media art shows how media and technology can be used to create poetic, aesthetic or imaginative experiences, opening different ways of thinking about technology that are critical or even radical.

With thanks to Stijn Dickel, Christoph De Boeck, Aernoudt Jacobs, Frank Theys, Kurt d’Haeseleer and Dirk De Wit for their input and feedback.

About the author

Ils Huygens is curator of contemporary art and design at Z33 House for Contemporary Art, Design & Architecture in Hasselt, where she curated exhibitions at the verge of art, science and society such as Space Odyssey 2.0, The School of Time, Learning from Deep Time and solo shows with Basim Magdy, Jasper Rigole and Kristof Vrancken (forthcoming). She co-curated two editions of Artefact Leuven: This Rare Earth: Stories from Below and The Act of Magic and CitadelArte (Diest). She is co-editor of the book Studio Time: Future Thinking in Art and Design. In her recent research she has focused mostly on the politics of time, and on exploring multispecies interactions crossing art, nature and science.