Morocco Intersections. Terugblik op een werkbezoek beeldende kunsten in Marrakech, Casablanca en Rabat.

ESAV, Marrakech (c) Samira Bendadi

Op uitnodiging van Kunstenpunt trokken Belgische kunstenprofessionals op werkbezoek naar Marrakech, Casablanca en Rabat. Ook journaliste Samira Bendadi (MO*) ging mee om verslag uit te brengen. Lees hieronder haar artikel.

Kunst in Marokko: een buikdans op muziek van de Marseillaise

Samira Bendadi reisde langs galerijen, kunstencentra en culturele projecten in Marokko. De dominante aanwezigheid van Frankrijk en de Franse taal stoorden haar, maar in een mondialiserende wereld is niets wat het lijkt. En ook dat wordt artistiek in vraag gesteld.

Daar kijken ze op hen neer en hier doen ze zoveel moeite om de Franse taal en cultuur te promoten’, regeerde de Frans-Brusselse kunstenaar Jérôme Giller toen ik een opmerking maakte over de opvallende aanwezigheid van het Institut Français in Marokko. Niet dat dat een totale verrassing was. Het is algemeen bekend dat Frans in Marokko een belangrijke taal is voor het overdragen en zelfs produceren van kennis en cultuur. En toch, de hyper aanwezigheid en zelfs de dominantie van de Franse taal en cultuur riepen vragen bij me op. Het gaf me in ieder geval het gevoel dat de hedendaagse kunstscène geparachuteerd was en dat het kunstwereldje iets elitairs was dat ver van de rest van de bevolking stond.

Neokolonialisme

Wat is kunst en wie bepaalt wat kunst is? Dat zijn de vragen die bij mij opkwamen. Geen nieuwe en verre van originele vragen natuurlijk. Het feit dat ik bij de taalkwestie ben blijven stil staan heeft voor een deel te maken met het feit dat ik uit België, en vooral uit Vlaanderen kom. Iemand die uit Frankrijk zou komen, zou het gewoon vanzelfsprekend vinden dat er in een Noord-Afrikaans land Frans wordt gesproken. Maar mij ging het natuurlijk niet alleen om de taal maar eerder om de neokoloniale dimensie in de aanwezigheid en in de activiteiten van de Franse culturele centra in Marokko.

Dat gevoel werd versterkt bij de opening op 27 september van de tentoonstelling Line of Flight van Zineb Sidera in de galerij Kult in de hoofdstad Rabat. Eén van de deelnemers uit mijn groep maakte meteen een parallel tussen het publiek in Rabat en het publiek bij een opening van een tentoonstelling in gelijk welk museum in Antwerpen of Brussel. ‘De codes zijn identiek’, zei ze. ‘Ik weet precies hoe ik me moet opmaken en welke rok ik moet dragen om erbij te horen. Maar dat doe ik niet. Ik ga nooit naar openingen’, zei ze.

De concurrentie tussen Europese landen houdt niet op bij het economische. Ook op cultureel vlak willen de grote landen liever geen nieuwkomers op hun terrein zien komen.

‘In tijden van mondialisering wordt alles geparachuteerd’, nuanceerde artiest, curator en onderzoeker Mohamed Rachdi toen ik hem later de vraag stelde. ‘De nieuwe technologieën, de reismogelijkheden, de bedrijven die zich overal inplanten, … Al die zaken maken dat ook kunst mondialiseert. En deze mondialisering gaat alleen maar toenemen’. In verband met de Franse invloeden verwees hij naar de historische banden met Frankrijk, naar het feit dat Marokko een Frans protectoraat was, en naar het feit dat er nog altijd Marokkaanse studenten zijn die in Frankrijk verder gaan studeren en zich specialiseren. ‘Het grootste Franse Lyceum in het buitenland bevindt zich in Casablanca. Marokko heeft het grootste aantal Franse culturele centra in vergelijking met andere landen’, zei Mohamed Rachdi nog.

‘Natuurlijk heeft Marokko zijn eigen identiteit en is daaraan gehecht’, zei hij nog. ‘Trouwens in de werken die Marokkaanse artiesten wereldwijd produceren is deze culturele identiteit altijd op één of andere manier aanwezig. Ook bij artiesten die een internationale carrière hebben kunnen opbouwen en zelfs bij artiesten die in Europa geboren en getogen zijn’.

Concurrentie

Dat Frankrijk bewust de eigen taal en cultuur promoveert in Afrika is niet nieuw. De Franse taal heeft op veel plaatsen terrein verloren ten voordele van de Engelse taal. En dat is ook in Marokko aan de orde, ondanks een elite die gehecht is aan de Franse taal en cultuur. Florence Robert-Vissy, directrice van het departement vormgeving bij ESAV (de hoge school voor film en beeldende kunsten in Marrakesh) verwees tijdens ons bezoek naar het feit dat haar school meer en meer leerlingen krijgt die hun middelbare school in het Engels hebben gedaan. Die overgang naar het Engels is nog erg beperkt maar is bezig.

De concurrentie tussen Europese landen houdt niet op bij het economische. Ook op cultureel vlak willen de grote landen liever geen nieuwkomers op hun terrein zien komen. Geen wonder dat de ontmoeting tussen Dirk De Wit, verantwoordelijke internationale relaties bij Kunstenpunt en zijn collega Lissa Kinnaer, met de directeurs van het Institut Français en het Goethe Instituut in Rabat niet meteen tot verdere afspraken leidde. Kunstenpunt, een organisatie die inhoudelijke ondersteuning biedt aan kunstenaars, wil de komende vier jaar focussen op de buurlanden waaronder de MENA-regio, het Midden-Oosten en Noord-Afrika. De reis naar Marokko kaderde in dat project van uitwisseling.

Door mensen te laten deelnemen aan culturele activiteiten, laat je hen meebeslissen.

AADEL ESSAADANI

Openbare ruimte versus galerij

‘Cultuur is geen luxe, cultuur is een noodzaak’, schrijft Aadel Essaadani, in de krant van zijn vereniging Racines. Ver van de wereld van de galerieën en de grote musea, werkt Racines met wat men het volk noemt. ‘Cultuur is de weg naar de democratie’, zei hij toen we de vereniging in Casablanca bezochten. Niemand mag uitgesloten worden van democratie en moderniteit, omdat hij arm is of analfabeet, vindt hij. En dus maakt de vereniging gebruik van de openbare ruimte en zoekt het publiek op.

‘Het is niet belangrijk om het te hebben over wat kunst is en wat cultuur is. Wat belangrijk is, is manieren vinden die de mens en de samenleving in het hart van het ontwikkelingsbeleid plaatst. Cultuur moet eigendom zijn van het volk, omdat cultuur een deel van de oplossing is’.

‘Door mensen te laten deelnemen aan culturele activiteiten, laat je hen meebeslissen. Cultuur kan mentaliteits- en gedragsveranderingen teweegbrengen en stelt mensen in staat om hun eigen moderniteit te creëren. De staat moet hierin een grote rol spelen’, vindt de coördinator van Racines.

Het is een andere benadering van kunst en cultuur. En die bestaat ook. Maar ook zij die behoren tot de hedendaagse kunstscène zoals die gepresenteerd wordt in galerijen en musea zijn niet helemaal blind voor de relatie met de Franse taal en cultuur.

In een video-installatie van de Frans-Algerijnse Zoulikha Bouabdellah, in het Museum van Afrikaanse Hedendaagse Kunst Al-Maaden in Marrakech, krijg je een blote buik te zien. Doekjes in de kleuren van de Franse vlag worden één na één rond de heup geknoopt. Daarna begint de buikdans, op het ritme van de Marseillaise, de nationale hymne van Frankrijk.

Over de tekst

Dit artikel is geschreven naar aanleiding van Morocco Intersections, een werkbezoek aan Marrakech, Casablanca en Rabat voor kunstenaars, curatoren en professionals uit de hedendaagse beeldende kunst in België. Meer informatie via Lissa Kinnaer.

Samira Bendadi schrijft voor MO* Magazine over diversiteit in eigen samenleving en de regio Noord-Afrika.

—————————————-

Persoonlijke impressies van de andere deelnemers

Mike Michiels – 3 cities in a bird’s eye view

The visit to Morocco was an intense and profound way to get to know the region. Staying in three very different cities (touristic Marrakech, governmental Rabat and harbour Casablanca) and seeing very different projects and artists gave us a good overview of what this country possibly has to offer. And that is a lot.

Being a country in full development where a lot of things are moving:

Morocco is a democracy but also a Kingdom where the King and his entourage still have real power. A financial elite and the history of French colonialisation add to the political complexity of the country.

With a lot of (Eastern) private and (some of it Western) public funding prestigious (building) projects are realised at this moment: on the one hand you have the resorts for tourists seeking a sense of Africa but not willing to give in on their Western toilet and on the other hand the big villa’s built for the rich Moroccan people and expats.

But apart from these we visited a private school for film, video, audio and graphic art founded by a Swiss couple, some private museums, interesting independent art spaces and commercial galleries. The impressive building of the Mohammed VI Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art showed us interesting works but left us with a sense of ‘nice building but what about the content’.

On the road we saw new public sports areas, parks, a very large scale theater in Casablanca (by Christian de Portzamparc), new train stations, a high speed train line,…

Most of these projects are from last decade. A question that immediately pops up into mind is whether the society itself is ready for all this? During our meeting with the people from Racines we could state that the answer is ‘no’. In a country where 50% of the people are illiterate and 60% is younger than 24 the need for a profound educational system is very high. But what can be the role of the Arts in this gap? Can art fulfill the need for education and stay with an aesthetic level. Which questions can it raise, which meetings can it facilitate? Is art meant for a rich elite group of art buyers searching for a local art market (a feeling I got visiting some of the projects of our program) or can it connect with the still very large group of people with a limited level of education and small revenues?

Meet: Léa Morin and Mohamed Fariji

We were invited by Léa Morin and Mohamed Fariji for a workshop titled ‘Collaborative and participatory art practices: a collective museum for Casablanca’, together with the participants from their Madrassa Programme. Madrassa is an educational program where young curators from the MENA are invited to participate in an intensive program of a week followed by a residency aiming to develop their practice and new projects inspired by the program.

Especially this workshop caught my attention during this trip, coming myself from a more a-typical organisation in the art world: vzw KAOS. With KAOS we develop art projects with artists with or without a psychiatric vulnerability. One of the projects KAOS develops is an Artist in Residence in psychiatry for international artists. Collaboration and participation are practices we also use in our projects.

The terms that had a central place in their projects are: ‘proposition’ and ‘negotiating’ (next to implementing). From bottom-up ‘propositions’, coming from artists or the general public, they discuss possibilities and negotiate these with the political authorities. They try to get a hold of empty spaces to give them a new public destination (compare to www.citymined.org in Brussels/London). An example of these projects is ‘L’Aquarium de Casablanca’ (collective and participative reflection on the future of abandoned spaces and the role of citizens in their re-activation). Other projects focus more on research and the support of young artists: ‘La Ruche’ where they invite recently graduated Moroccan artists to develop their work and art practice in a project funded by the Ministry of Culture. ‘Les Invisibles’ is a research project retracing a possible writing of histories (art, cinema, society, etc). This takes the form of publications, restoration work, workshops, seminars, etc.

Next to this they work on the ongoing project ‘Le Musée collectif’ where they gather together with everybody who is interested in the history of a place, ideas, stories, etc. Through different media (found footage, film, photography, sounds, objects, ..) they create the ‘history of things and places’ to give it back to the public. A collective memory of cities is assembled like this since Morocco doesn’t have a public archive available for their inhabitants. With a not always so nice history of colonialism by France and politics dominated by some strong-willed kings the history is kept locked behind doors.

How to involve people not interested in the Arts, not familiar or daring to step into arts institutions, a museum, etc. in these projects? In the cases proposed by Fariji and Morin: by going literally towards them. Not only with ‘Le Musée collectif’ where neighbours are invited to participate or are questioned on certain places, happenings,.. but also by a temporary structure designed by architects that will tour different cities/villages during a year (1 month at every stop of the tour) and hosting the ‘collection’, organizing ateliers, etc. In the meantime the project also grows with new discoveries and new additions in ‘la récupération de la mémoire’ as Fariji and Morin call it.

Finally they also have the project ‘La Serre’ where a moveable structure in the form of a ‘serre’ (a greenhouse) is moved around to different areas and different cities. This temporary space is a platform for experimentation at the crossroads of contemporary art and botany where people can organize or participate in workshops, discuss their ideas around a cup of tea and launch their ‘propositions’.

One of the main points of all of their projects is to start from the ‘possibilities’ and not from the problems. All this in a subtle way: through networking/discussion a lot can be achieved. They don’t aim to ‘fight against’ the official authorities but ‘work together’ on the development of new ideas and projects. In general you could say that this is a way of working that appears to me in more projects we visited: starting from the basis working on bottom-up projects (ex: Fariji and Morin, Racines, independent art space H2 which is however completely funded by Société Générale, Atelier Eric Van Hove who’s trying to implement new possibilities for the craftsmen for which Morocco used to be famous but are disappearing because of cheaper production methods and import from China) in collaboration with the top-down partners (Ministry of Culture) to actually improve and install new projects, ideas, work on emancipation, …

For me all these projects seem to prove that a lot is possible if only you dare to think out of the box (public vs private funding) and aim for new coalitions. Or how a society in full development often seen through paternalistic Western glasses can actually be an inspiring mirror for the problems (or must I say ‘possibilities’) we face in our own little country/region.

—————————————-

Tom Nys – Reflections on a Laughing Cow

When strolling through whichever major city or any small town in Morocco, one will notice that three things visually dominate the local street view. First, there are the football jerseys. I was already well aware of the fact that Moroccans love the ball game as well as the culture that surrounds it since I live in Borgerhout, a district in Antwerp that is predominantly inhabited by Moroccan émigrés. In my neighbourhood, the obsession with footie is very often combined with a tribal pride: shirts from the national team prevail. In Morocco itself, however, outfits from European sides are most common, with FC Barcelona out front. As we visited the North-African country with a group of delegates from the Belgian art world, Barça won its Champion’s League game against Sporting Clube de Portugal with a tight 0–1 and more importantly, they got political too, siding with the Catalonian government that was about to declare independence from Spain in a string of tension-ridden events. Sports have never been devoid of politics, of course.

Secondly, it is hard to avoid the images depicting King Mohammed VI, which apparently come in multiple variations. In Rabat, we even encountered a store selling these portraits, in a display not unlike an art gallery. Of course it is not done to publicly grin at or even to mock those, how tempting this sometimes might be — there is one where he dons 1990s “The Matrix”-like sunglasses and casually holds a cigarette –, because the man is really adored by many. Moreover, the realisation that someone may be watching you closely isn’t even a paranoid thought. We have heard it on several occasions during our trip and noticed it firsthand in quite a few instances that, after all, Morocco is still a kind of monarchic dictatorship, in spite of all the progress that it is making in terms of political values.

Last but not least, the pleasant smile of a female figure with a reddish tan and bejewelled with big earrings is impossible to ignore; it is the logo of the popular French cheese brand La Vache Qui Rit, or The Laughing Cow, that seems to be everywhere. We enjoyed amazing cooking — and drinks — in Morocco, and especially the copious tajine dishes that were served for dinner at artist Eric Van Hove’s roof terrace in Casablanca, which he kindly furnished to host a gathering of local art practitioners and professionals, will stick in our gustatory memory for a long while. Yet La Vache Qui Rit (Al-Baqarah Ad-Dahika in Arabic) is staple food for most Moroccans, which they smear on khobz or msemen. You can order it at most bakery stores.

The brand, which is part of Fromageries Bel SA, has been around since 1921 and can be found all over the world. In Morocco, there are several production plants and according to Euromonitor, it held a market share in the overall cheese category of 30% last year. The cow on the familiar, round packaging was originally drawn by the company’s founder, but was later redesigned into the famous, friendly animal we now all know. During our trip, we spotted it in several guises: sometimes it wore a small, black top hat, in a few cases it had a full body and in one particular version, the creature stood upright with crossed arms and looked at you with an assertive gaze.

Perpetual Patterns

What fascinates me specifically about the logo is the fact that it is a splendid example of the so-called Droste Effect: the laughing cow wears earrings that are comprised of round boxes that feature the laughing cow who wears earrings that are comprised of round boxes that feature… Ad infinitum. My interest in endless repetition stems first and foremost from my love for techno music, in which beats, musical units and small patterns are replicated seemingly endlessly. The sole limitation of a techno track lies in its carrier: the maximum time a record or audio file permits; otherwise it might just as well go on forever and a dj mix is in fact a way to overcome this boundary. Incidentally, repetitiveness is found in a lot of Arab music too, like in Sufi music that exploits this trance-inducing feature in the most beautiful ways.

In the visual realm of the North-African cities we explored during this tour, cases of the recurrence of imagery and of repetitive ornamentation were to be found plentiful. As we were in a Muslim country, the artistic tradition was obviously extremely decorative, for the depiction of living creatures was considered blasphemous; hence the beautiful pattern designs in crafts. These crafts, like ceramics and pottery, textile and tapestry art, metalwork and wood sculpture, have always been strongly encouraged not only by the monarchs but by the French colonisers as well. Nowadays, the main customers for these fine goods are mostly tourists but since the rise of low-cost airlines and budget holidays, they have to be small and cheap, which has led to quality degradation and the allocation of production. Your beautiful silverware bought in a Marrakesh souk probably isn’t silver at all and almost certainly was made in China. A substantial premise of Eric Van Hove’s projects in Morocco is in fact to give back local craftsmen their pride — and source of income.

The permanent collection of the Musée Mohammed VI d’Art Moderne et Contemporain proved that only long after modernism, the ornamental reflex that was brought about by religion waned. Still, although the King is one of the most important collectors in contemporary art, government funding maintains its focus on crafts. Indeed, the King influences officials and people from the establishment to follow his example so there definitely is a contemporary arts market, albeit a small one, but state subsidies for the field of art are frustratingly weak. Art venues of different scale are invariably sponsored by private initiatives, from the small art space and residency Le 18 in Marrakesh, with its impressive international and forward-thinking programme that is paid for by a group of restaurant owners to the Musée d’Art Contemporain Africain Al Maaden (MACAAL), a posh museum within a golf resort outside of Marrakesh that hosts the marvellous collection of a couple that made its fortune in real estate. It was a theme that recurred in conversations as often as La Vache Qui Rit was spotted.

The Goat and the Pentagram

The Droste Effect that the figure of the laughing cow illustrates so well, is of course almost synonymous to the concept of the mise en abyme, and during a modest curatorial exercise we did in Casablanca, together with the participants of the Madrassa programme, which is aimed at local, contemporary curatorial practices, we came across a real, truly vertiginous case in point. Meeting and hanging out with the Madrassa people was, by the way, an absolute bonus of our trip and engaging in one of their workshops was not only enriching but also fun. I joined a group that was sent to the lighthouse in the Al Hank district of the city, a poorer part on a peninsular tip that isn’t on most tourist maps. The purpose was to gather information and pieces of evidence about the assigned place in order to build a kind of alternative and informal archive that would deal with parts of Casablanca’s modernist history so as to rescue these from oblivion. This would become part of a so-called Collective Museum.

In an area next to the ocean, right behind an outpost of less fortunate city dwellers but close to sports and entertainment facilities for those who are better off, the white tower rose up against a backdrop of a dreamy blue sky. The whole locale was rich with contrasts. We passed some old walls full of graffiti declaring love for the district, demonstrating the presence of the Green Boys — football team Raja Casablanca’s ultras — and defying police authority, and were met by the man who solitarily operated and maintained the lighthouse. He held that job for more than thirty-seven years and told us that he rarely greeted foreign visitors. While he let us enter the high building, a herd of goats insouciantly strolled across the road.

Earlier that day, we had visited curator Mohamed Rachdi’s apartment for an interesting talk about his activities and views on contemporary art in Morocco. His residence was being refurbished and would serve as an art space in the near future. It was on the eleventh floor of a huge block and I had been cocksure to not take the elevator but the stairway, which eventually seemed endless. I was convinced I had done enough physical exercise for the day when I finally arrived. However, at the lighthouse, another flight of stairs awaited and this time there was no elevator to consider. Upon reaching the top of the tower, I looked down the spiral staircase panting and saw a Moroccan star tessellated on the floor. The outlook resembled a mise en abyme perfectly. Nevertheless, I did not think of laughing cows but of goats while black dots floated before my eyes. The Moroccan star turned into a pentagram. It instigated fragments of Scandinavian black metal going through my mind.

Luckily these strange, satanic delusions disappeared when I stepped onto the sun-lit balcony of the lighthouse and perceived the most beautiful view: the ocean bordering the cityscape of Casablanca, with its grand mosque only one and a half kilometres away. I was told that it is the second largest in the world and seeing it from here, it looked enormous indeed. The black metal was substituted by the adhan I had heard so many times here; in Casablanca the muezzin from the house of prayer close to our hotel had a dreadfully coarse and loud voice but in Marrakesh it was recited in a soothing, beautiful way and it was the latter version that now sounded in my brain. Upon returning to the École des Beaux-Arts where Madrassa held its sessions, the musical atmosphere changed once more when our taxi driver played some contemporary Arab music on his stereo. Ultimately, he gave me a copied cd with awesome chaabi from popular artists such as Said Senhaji and Hamid El Mardi, which I currently use to blast through my car speakers when cruising through my Antwerp quarter. My neighbours love that, the local police officers don’t.

The Laughing Capitalist

Witnessing the sheer amount of laughing cows in Morocco’s everyday life made me recall the artwork “On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life” by fellow-countryman Wim Delvoye, which was shown for the first time at the Lyon Biennial in 2005 and which is another employ of the recurrence of a singular motif. After all, it embodies more than four thousand labels of La Vache Qui Rit boxes, a personal collection that the artist has built up over many years. Bel, the mother company, was moved by Delvoye’s amassment and appointed him recently to design a collector’s item box on the occasion of their one hundredth anniversary in 2021, just as Thomas Bayrle, Hans-Peter Feldmann and Jonathan Monk were before him.

The French company has obviously pervaded Moroccan eating culture profoundly. In this respect, it is not unimportant to point out that France, the former coloniser of Morocco, still leaves its marks deeply on the North-African country. This is not only noticeable in terms of economics but on almost all levels of society. In the cultural domain one cannot ignore the fact that the Institut Français has a strong foothold here. It competes with the Cervantes Institute and several German institutions, which all invest in cultural affairs and which can rely on budgets that far exceed the resources of Morocco’s cultural department. A large number of festivals take place here, celebrating literature, film, music, dance and other art forms, and the money consistently comes from one or the other foreign cultural organisation. Of course this always seems to be a wonderfully generous affair but rest assured that deep down, economical factors are at the heart of all this. I reckoned there is a perverse, capitalist and even neo-colonialist reasoning of the French behind the decision to fund culture in Morocco so heavily, while their banlieues that are populated by a great deal of Maghrebis are left to rot or given over to rich real estate firms.

It’s surely a sour note to end my thoughts on a country that proved to have rich cultural traditions of its own, where I met extremely hospitable people, that demonstrated to have many possibilities in terms of art and where many motivated people made up the local art world, and that these reflections were sparked by a tasteful type of cheese. However, there still is a long way to go. I could not have wished for a better conclusion than what I saw when I walked onto my street in Antwerp on my way home. In a parked Renault vehicle, I spotted a La Vache Qui Rit shopping bag on top of a blue, cardboard box with big letters that spelled “Europa”… Like a snake biting its own tail, or another mise en abyme.

—————————————-

Phillip Van den Bossche (MU.ZEE) – How to unthink something you don’t know you’re thinking?

Wie spreekt? Wie luistert? En waarom? Deze drie korte vragen houden me al een tijd lang bezig. Tijdens de studiereis naar Marrakesh, Rabat en Casablanca zijn ze ook meermaals indirect en in wisselende gesprekken komen bovendrijven. Het reizen in groep heeft het voordeel dat er vele, korte ‘tussengesprekken’ plaatsvinden: onderweg van de ene afspraak naar de andere, in de bus of trein, en als reactie op een presentatie of bezoek. Bovendien is er de mogelijkheid om niet afgeronde gedachten na een dag, als de omstandigheden zich wederom voordoen, verder te zetten en op die manier terug te komen op een observatie. De rol van de observator blijft daarbinnen altijd ambigu, want (in milde vraagvorm geformuleerd): hebben we als westerse reiziger geen geprivilegieerde positie en blik?

Vandaag de dag word je in een links hoekje met zogenaamde culturele zelfhaat weggezet als je de woorden ‘Europese leegte’ hanteert, of minder uitgesproken, als je het aandurft de westerse cultuurgeschiedenis (laat staan het imperialisme) in vraag te stellen en te wijzen op andere niet-westerse visies en bronnen. Dit klinkt als een uitweiding in een reisverslag, maar maakt er wel degelijk deel van uit. Want het onderzoek dat voortvloeit uit deze studiereis en waarmee we allemaal zijn teruggekeerd naar onze kunstplekken en musea valt voor mij samen te vatten in de zin: how to unthink something you don’t know you are thinking.

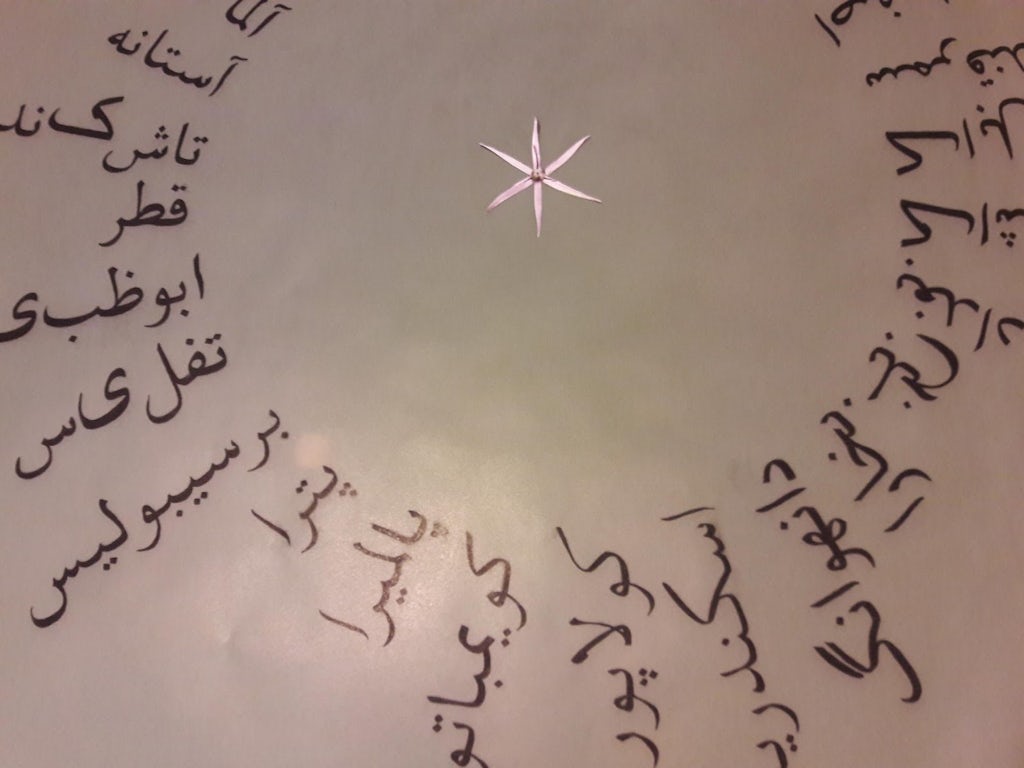

Een reis is altijd een beginpunt. En Europa is al lang geen eiland meer. Voor een jonge generatie Marokkanen is Engels en niet Frans de tweede taal geworden. Zuid kijkt niet alleen meer naar Noord. Integendeel, de diaspora toont de ontelbare verbindingen tussen zowel Zuid en Noord, West en Oost, tussen bijvoorbeeld de Maghreblanden en het Midden-Oosten. Hedendaagse kunst is veel meer dan een product of de ego-tuin van een ondernemer-kunstenaar. Vandaag is de hedendaagse kunstwereld een superdivers denkkader om maatschappelijke en esthetische vragen te formuleren. Het is een cirkel waar kunstenaars, denkers, schrijvers en tentoonstellingsmakers elkaar vinden.

In Marrakesh, Rabat en Casablanca hebben we kunnen kennismaken met een grote reeks kleine en grote initiatieven. Voor het overgrote deel zijn het private initiatieven (van individuelen of kleine collectieven), soms gekoppeld aan minieme bijdragen of subsidies uit de internationale, semipublieke ngo-sector. Opvallend is de specifieke en geëngageerde diversiteit aan invalshoeken. De ene plek legt zich toe op het uitgeven van kunstboeken en kunstkritiek, een andere ruimte heeft een bibliotheek samengesteld of nog elders, zien we de combinatie tussen een artist-in-residence en het denken over de praktijk van de curator. De verhouding tussen publieke musea en private kunstruimtes in Marokko is volledig verschillend van de kunstcontext in Vlaanderen. Perspectiefwissel is dan ook makkelijker gezegd dan gedaan, want hoeveel informatie kunnen we in een korte studiereis vergaren? Wat doet een privémuseum in een golf resort, een bibliotheek met een educatief en een literair vertalingsprogramma in een luxe hotelcomplex, wat als een onafhankelijke organisatie het beleid van een minister van cultuur met cijfermateriaal kan aanwakkeren en daarom subsidie weigert te aanvaarden. Of nog, waarom is de enige filmacademie in het land opgericht door een Zwitsers echtpaar? De tegenstellingen laten zich evengoed makkelijk formuleren. Misschien dient de discussie echter niet te gaan over de voor- en nadelen, de belangrijkheid van publiek versus privé, en kunnen we de dualiteit loslaten en vervangen door de vragen: hoe worden keuzes geformuleerd en beslissingen genomen; welke open vorm van democratische besluitvorming wordt gehanteerd? Op deze manier krijgt het denken over private én publieke uitwisseling een meer hybride, meervoudige invulling — in Marokko deels uit noodzaak omwille van de eigen koninklijke en politieke geschiedenis. En daar valt veel uit te leren.

‘Madrassa’ is het Arabische woord voor school en tevens de naam voor een regionaal programma in Casablanca, Amman, Alexandria en Algiers ‘of residencies, meetings and trainings in contemporary curatorial practices’. Tijdens onze studiereis hebben we zo goed als twee dagen met deze groep gedeeld. Het grensoverschrijdend uitwisselen van informatie en verhalen heeft voor mij deze studiereis tot een ontdekking en nieuw beginpunt gemaakt. Anekdotes zijn voor later. Of één dan — via youtube makkelijk te vinden bovendien: Ik denk aan een kort gesprek met Samira Bendadi op de kunstacademie over Nass El Ghiwane en hun lied “Siniya” (Ou le plaisir de partager) uit 1973.

Met dank aan Hicham Khalidi en Léa Morin, de samenstellers van het programma.

—————————————-

Sam Eggermont – Met Maghreb en Hicham in bad

Verwachtte ik soeks, zand, sigaretten.

Clichés snel aan diggelen, niet dat ze er niet zijn, maar er toont zich meer, vele lagen. Subtiel.

Marrakesh (land van God en van 1,5 miljoen inwoners) koestert zich rondom de Medina, de drukke autoloze kern met zijn tijdloos verleden; de tropische hitte verraadt de woestijn en het Atlasgebergte.

De residentie ‘Le 18’ is veel idyllischer dan andere plekken. Daarom?

Le 18 gesponsord door 3 plaatselijke restaurants.

Het sociale project van Queens Collective helpt de plaatselijke vrouwelijke jeugd, een vrijplaats tegen het traditionele isolement van de vrouw.

Buiten de Medina zijn er ‘andere’ privé-initiatieven.

‘L’ESAV, Ecole Supérieure des Arts Visuels’ en ‘Musée d’art contemporain Africain el Maaden’.

‘Comptoir des Mines Galerie’ en de ‘Voice Gallery’, galleries met residentie en ambitie.

De literaire residentie Dar al Ma’mûn art centre & residency temidden van een resort-for-the-well off.

De buitenwijken zijn een allegaar aan bouwprojecten, resorts, buitenlandse investeerders, een chaos, niet direct ingebed in dat dorre landschap.

Die avond bij Eric Van Hove doet goed door het atelier van de kunstenaar, de ondernemer en de verteller, door het dakterras, door nieuwe ontmoetingen en de felle discussies over diens project.

Casablanca en zijn 3,5 miljoen inwoners verwelkomen ons met wat regen in zijn Europese straten, het auto-geharrewar, de voetgangersverachting, het nachtlawaai en zijn mildere klimaat.

Heimwee naar Marrakesh.

Een dag later toont Casa zijn dynamiek, bron van talrijke privé-initiatieven, een stad die bloeit en schopt, ook tegen schenen van de teruggetrokken overheid middels initiatief te nemen, te netwerken en opleidingen te starten; klein kunstenlandschap maar sterk internationaal geconnecteerd.

Casa is een plaats van heden en toekomst, van teruggekeerde opgeleide Marokkanen.

L’Atelier de l’Observatoire (het curatorenprogramma Madrassa) in l’école des beaux-arts, Mohamed (Société générale) de gepassioneerde op de 11-étage, Musée Slaoui met een curatoren-ontmoeting (LIMIDITI), meerdere galeries en tenslotte de ontmoeting met de kunstvakbond van Marokko: Racines, artmap.ma. Steunpunt, belangenvereniging en onderzoekscentrum met eigen middelen.

Tussenin een dag Rabat.

Brede lanen, zuurstof en zee en opvallend langzaam verkeer.

Le Cube, kleine residentie met presentatiemogelijkheid, vernetwerkt.

L’Appartement 22, kleine residentie met presentatiemogelijkheid, vernetwerkt.

Staatsmuseum Musée Mohammed VI, roeit met koningsriemen.

Opening bij Kulte Gallery met interessant publicatieplatform en receptiemodel en met het stereotiepe beau-monde-volk.

Drie steden, drie sferen en dynamieken.

Een immens enthousiasme, drive. Kritische (politieke) blik.

Privégeld, privésponsoring, privé-armoede.

Open internationaal (de Mena, La France, Europa).

Moskee, gebed, alcohol, thee. Toch clichés.

Het blijft aan je kleven door mix van koloniaal verleden, opstanding, kritiek en fierheid.

—————————————-

Louise Osieka & Isabel Van Bos – Een collectief museum?

Waar onder de dynastie van koning Hassan II (1961–1999) kunstenaars worden beschouwd als verraders en kritische kunstproductie en presentatie in de kiem wordt gesnoerd, muteert Marokko na de kroning van koning Mohammed VI in 1999 naar een progressiever klimaat met een mildere houding ten opzichte van de hedendaagse kunst. Een nieuwe generatie instituten en stichtingen zien het levenslicht, grotendeels ondersteund door private fondsen en eerder sporadisch door nationale projectsubsidies of internationale kunstinstellingen.

In 2004 stichten Vanessa Branson en Abel Damoussi een non profit vereniging dat vanaf 2009 wordt omgedoopt tot de Biënnale van Marrakech. In datzelfde jaar sticht Meryem Sebti kunstmagazine Diptyk dat als eerste een vijfjaarlijks relaas van de hedendaagse kunstscene in Marokko en in de bredere Maghreb regio brengt. Een ander fundament wordt in 2014 gelegd door de koning zelf met de oprichting van het eerste Marokkaanse museum — Musée Mohammed VI d’Art Moderne et Contemporain in Casablanca — dat volledig gericht is op moderne en hedendaagse kunst en daarbij conform de internationale museale normen werkt. Het museum bezit een permanente collectie die de binnenlandse kunsten van het begin van de twintigste eeuw tot heden publiek toegankelijk maakt. Daarnaast verleent het haar infrastructuur voor tijdelijke tentoonstellingen zoals Femmes, Artistes Marocaines de la Modernité, 1960–2016.

Desalniettemin blijven de gewonnen vrijheden beperkt. Culturele actoren leven vaak op gespannen voet met de huidige politieke en religieuze leiders. Het gebrek aan infrastructurele en financiële overheidsondersteuning creëert een kunstenveld waar initiatieven terugvallen op traditionele Westerse presentatiemodellen in veelal monumentale belevingsarchitectuur gebouwd dankzij privaat of buitenlands geld. Deze instituten — wiens bestaansrecht we niet ter discussie willen stellen — fungeren als podia voor gevestigde nationale of internationaal gerenommeerde kunstenaars met een groot aandeel in de commerciële internationale kunstmarkt.

Het is in deze, ruw geschetste, context dat hybride initiatieven als Espace 150 x 295 (initiatief van kunstenaars Batoul S’Himi & Faouzi Laatiris ), Cinémathèque de Tanger (initiatief kunstenaar Yto Barrada), Le Cube (initiatief van curator Elisabeth Piskernik), Kulte Gallery & Editions, Appartement 22 (initiatief van curator Abdellah Karroum), L’Atelier de l’Observatoire (initiatief van kunstenaar Mohamed Fariji) en Le 18 (initiatief van kunstenaars Laila Hida enHicham Bouzid) een alternatief trachten te bieden. Deze organisaties vertrekken vanuit de noden van de individuele kunstenaarspraktijk en zijn vaak bottom-up of artist-run georiënteerd. Door het opereren in een politiek en financieel ongunstig klimaat werken ze buiten de traditionele Westerse presentatiemodellen en experimenteren op non-hiërarchische wijze met verschillende productie- en presentatie formats. Zij zetten daarbij in op drie belangrijke pijlers; de presentatie van opkomende en niet mercantiele kunstenaars (Appartement 22, l’Atelier de l’Observatoire, Le Cube, Espace 150 x 295 etc. ); het onder de aandacht brengen en archiveren van (kwetsbare) geschiedenissen (Cinémathèque de Tanger en L’Atelier de l’Observatoire) en educatie (Madrassa).

Hun activiteiten vinden niet enkel plaats in de drie grote centra (het toeristische Marrakech, de havenstad Casablanca en het bestuurlijke Rabat) maar ook in de periferie, op het platteland en in de marges van de geconcentreerde stad. Zo ligt de basis van L’Atelier de l’Observatoire — in 2012 opgericht door kunstenaar Mohamed Fariji en curator Léa Morin — op 32 km van Casablanca in de rurale regio van Bouskoura. De site functioneert als een workshop toegankelijk voor een breed publiek en uitgerust met een ruime werkplaats, residentie, een serre en een organische groententuin. De serre, een lang uitgerekte ovalen structuur overspannen met plastiek, is een artistiek project geïnitieerd door Fariji in 2014. De serre — La Serre — wordt geclaimd als publieke ruimte en doet dienst als ontmoetingsplek voor de observatie, ontwikkeling en het debat omtrent nieuwe ideeën, stemmen en projecten wars van de dominante ideologieën en dogmatische formats. La Serre is slechts één van de zes projecten waarin L’Atelier de l’Observatoire zijn experimentele visie op basis van de drie bovengenoemde pijlers vormgeeft. Met het project genaamd La Ruche verlenen ze inhoudelijke en productionele ondersteuning aan opkomende Marokkaanse kunstenaars; Les Invisibles is een onderzoekscel die zich richt op de schijnbare marges van geschiedschrijving zoals bijvoorbeeld de ondergesneeuwde nationale filmgeschiedenis; Madrassa (Arabisch voor ‘school’) is een regionaal collectief dat de hedendaagse curatoriële praktijk in de Maghreb regio en het Midden-Oosten onderzoekt en stimuleert; L’Aquarium gaat net als La Serre terug op een project geïnitieerd door Fariji en is gericht op het collectief debat rond de herbestemming van het voormalige aquarium van Casablanca en ten slotte Le Musée Collectif, een merkwaardige pleister op de wonde van een stad zonder publiek museum of archief en dus zonder collectief geheugen.

Le Musée Collectif vertrok initieel, net zoals La Serre en L’Aquarium, vanuit de individuele kunstenaarspraktijk en de door Fariji aangestipte noodzaak om de sporen van vergeten, verwaarloosde of dikwijls zelfs verdwenen objecten en documenten, films, foto’s te verzamelen onder de noemer ‘geheugen-objecten’. In de herfst van 2015 startte Fariji samen met een groep geëngageerde burgers en kunstenaars een onderhandeling met de stad en met een grote vastgoedontwikkelaar om het mythische Parc Yasmina, een voormalig kinderpretpark, te herwaarderen. In het kader van een grootschalig gentrificatie plan voor het park en omliggende wijken, slaagde Fariji erin alle fysieke sporen van het ‘irrelevante’ pretpark te recuperen. Hij repareerde enkele attracties en bracht ze in een andere wijk terug in werking. Het pretpark kwam — verplaatst in tijd en ruimte — terug tot leven en haar geschiedenis werd aan de hand van een wisselende collectie aan documenten, foto’s, video’s en souvenirs in een DIY museum gedocumenteerd. De ‘geheugen-objecten’ fungeren er als katalysatoren voor een debat over én in de publieke ruimte.

Bijzonder aan dit collectief langetermijnproject is dat het de persoonlijke en daardoor mogelijk anekdotische interpretatie van de kunstenaar overstijgt. Le Musée Collectif is een museum zonder infrastructuur en verwelkomt als nomadisch platform alle materiële sporen van vergeten, gemarginaliseerde of de kop ingedrukte onderwerpen. Ondanks dat er wel degelijk fysieke objecten worden verzameld, is deze collectie inferieur aan de act van verzamelen en dus het denken over verzamelen. Le Musée Collectif formuleert een onofficieel verleden op basis van collectieve verhalen. De kunstenaar staat er, naast de burger, in het heden en is er op integrale manier bezorgd om het verleden en geeft er op geëngageerde manier vorm aan de toekomst. Een (vaste) collectie is allesbehalve een voorwaarde.

Le Musée Collectif is daarom mogelijk emblematisch voor een debat dat hier in Brussel wordt gevoerd, zij het in een andere politieke en socio-economische context. Hoe moet het museum van de toekomst (en het toekomstige museum in de Citroëngarage aan het kanaal in Brussel Noord) er uit zien? Wat hoort ze te doen en wat niet? Welke methodologieën moet ze gebruiken? Waar bakent ze af en waar zet ze haar bakens open? Het toekomstige museum van hedendaagse kunst in Brussel zal zich (hopelijk) op kritische manier verhouden tot onze eeuwenlange traditie van verzamelen. Ze zal een hedendaags antwoord moeten bieden op de bestaande homogene collecties die gericht zijn op één nationale identiteit met duidelijk afgebakende parameters wat betreft taal, cultuur en territorium. Hiervoor zullen beleidsmakers en zij die het toekomstige museum in de praktijk vormgeven bereid moeten zijn om de geijkte paden te verlaten willen ze een collectieve ontmoetingsplek voor de talrijke heterogene transnationale en transculturele identiteiten aanwezig in Brussel en de ruimere regio. De kans is groot dat het antwoord — al zij het gedeeltelijk — op 32 km van Casablanca te vinden is.

Deze tekst kwam tot stand dankzij een gesprek tussen Louise Osieka & Isabel Van Bos en Léa Morin & Mohamed Fariji (L’Atelier de l’Observatoire) in Casablanca op 28 september 2017 in het kader van Morocco Intersections georganiseerd door Flanders Arts Institute (24–28.09.2017) en de tekstuele bijdragen in de publicatie Future Imperfect: Contemporary Art Practices and Cultural Institutions in the Middle East, edited by Anthony Downey and with a contribution by Léa Morin, (Sternberg Press, 2016).

—————————————-

Jérôme Giller – Impressions urbaines du Maroc. Notes sur l’art dans l’espace public

La médina

La Médina, ancienne ville et centre historique des villes marocaines d’aujourd’hui, se caractérise par un dédale de rues étroites qui forme un plan urbain labyrinthique.

L’étranger qui s’y aventure seul, y est désorienté et s’y perd.

L’absence de nom donné aux rues renforce l’impression d’un dédale infini dont il ne sortira jamais.

Chaque marocain a une connaissance vernaculaire de la Médina. Les repères urbains et les chemins parcourus dans la Médina s’acquierent par la pratique et sont propres à chacun.

ré-activer (re-enactement) le dispositif de Stanley Brown : « This way Brown ! ». Demander à un habitant comment se rendre dans tel lieu de la Médina et lui demander de dessiner le plan et nommer ses repères. Etablir un corpus de cartes subjectives de la Médina.

Le plan urbain de la Médina semble s’être construit de manière empirique à la faveur des possibilités d’acquisition des terrains à bâtir par les habitants des villes.

Ce plan d’apparence anarchique et organique s’organise en zones d’activités :

– le Souk (qui signifie marché en arabe) regroupe les commerçants et certains ateliers de fabrication d’objets usuels

– les quartiers industriels : industrie des tanneries, industrie du tissage, etc.

– les quartiers d’habitations et pavillonnaires entre les zones d’activités et en périphérie de la Médina, comme les Riads par exemple.

La Médina est la plus grande réussite urbaine des villes marocaines. Outre, l’effet labyrinthique et le plaisir qu’on éprouve à s’y promener et s’y perdre, les rues étroites qui peuvent être facilement couvertes, favorisent l’ombre et apportent de la fraîcheur dans la ville.

Le plan urbain de la Médina est une réponse écologique aux conditions climatiques du pays.

Ce modèle urbain, plan labyrinthique et rues étroites qui favorisent l’ombre, a été reproduit pour la construction de nouveaux quartiers ouvriers dans les grandes villes lors du protectorat français : quartier des Habbous à Casablanca, quartier M’Sellah à Tanger par exemple.

La première périphérie « haussmaniènne »

Le plan urbain de la première périphérie des grandes villes marocaines (Marrakech, Rabat, Casablanca, Tanger), qui touche l’enceinte de la Médina, a subi l’influence du génie civil occidental pendant les périodes de la colonisation et du protectorat.

Le modèle « haussmanien » s’est imposé et a été appliqué pour dessiner les grandes artères de circulation et bâtir des bâtiments « à l’occidental » en façade de rue.

Ce modèle urbanistique et architectural donne un aspect occidental aux grandes villes marocaines, comme Rabat, Casablanca et Tanger.

Les grandes villes marocaines ont été des laboratoires expérimentaux pour l’urbanisme et l’architecture art-déco et moderniste occidentaux.

La californisation suburbaine

La nouvelle périphérie des villes marocaines souffre de ce que les urbanistes nomment aujourd’hui la californisation de l’espace urbain, modèle importé de la côte Ouest des Etats-Unis.

Ces nouveaux quartiers sont organisés selon le principe du plan carré. Sur chaque parcelle de terrain est construit un bloc d’habitation de plusieurs étages.

Les rues sont larges. Le soleil s’y engouffre facilement. Il y fait très chaud.

Ces quartiers ressemblent à ce que Bruce Bégout, philosophe, définit comme la suburbia : l’espace urbain de l’étendue qui n’a pas de centre référentiel.

Un espace urbain de l’emplacement construit comme une succession de séquences répétitives : bloc d’habitation, chancre urbain, bloc d’habitation, parking de voiture, centre commercial, friche, bloc d’habitation, etc.

A cause de son étendue, la suburbia se pratique en voiture. Elle se regarde derrière l’écran du pare-brise et se vit dans l’air conditionné de la climatisation.

Dans ces nouveaux quartiers, tous les appartements sont équipés de climatisation. En comparaison avec le modèle urbain de la Médina, ils sont énergivores.

L’effet produit par ces nouveaux quartiers est celui d’une ville à l’étendue infinie, mais qui, paradoxalement, paraît déjà en ruine, détruite par la guerre ou par une catastrophe écologique. A les parcourir on ressent le sentiment d’une désertification de la ville : comme si les habitants avaient disparus.

Murs, enclos et bordures : intérieur / extérieur

L’espace de toute chose construite est enclose par des murs.

Les palmeraies sont encloses derrière des murs.

Les quartiers périphériques sont enclos derrière des murs.

Les palais royaux sont enclos derrière des murs.

La médina est enclose derrière un mur.

Le riad est enclos derrière un mur.

Les murs voilent l’intérieur des choses aux regards extérieurs.

L’espace de la ville marocaine s’organise selon une succession de bordures.

C’est comme si la ville marocaine était construite par une succession d’intériorité /extériorité qui s’emboitent les uns dans les autres à l’image d’une poupée gigogne.

Les murs-bordures des maisons sont hauts, neutres, austères, avec un minimum d’ouvertures pour protéger de la chaleur.

Il n’y a pas de décoration en façade, sauf autour des portes d’entrée.

La décoration signale alors le passage de l’extériorité à l’intériorité.

L’intérieur des maisons est, au contraire des façades extérieures, saturé de décoration et de motifs. Entrer dans une maison marocaine c’est faire un passage brutal entre la rudesse esthétique de l’espace extérieur de la rue et l’abondante richesse des motifs de l’espace intérieur privé.

Le Riad

Le Riad (qui signifie jardin en arabe) est organisé de la même manière, par emboitement d’intériorités et d’extériorités.

Des appartements ou chambres privées (intériorité), étagés en balcon sont tournés sur un patio central, un salon et une salle à manger, qui forment l’extériorité du Riad : le “lieu public” du Riad où les habitants se rencontrent.

Notes sur la rue

Toute la rue est un seul et même espace partagé entre le commerce et la circulation ; entre artisans, marchands, piétons, et moyens de transporteurs : animaux (ânes) et véhicules à moteur (deux roues, voitures, camions).

La rue de la Médina (comme dans les quartiers populaires des grandes villes) est une vitrine à ciel ouvert.

Les étales de marchandises s’exposent en rue. Les commerces n’ont pas de vitrine comme en Europe : les échoppes comme les ateliers de fabrication et de réparation donnent directement sur la rue.

La rue regorge de personnes qui exercent un « petit métier » : vendeurs de figues de barbarie, vendeurs de jus de grenadine. Vendeurs de cigarettes. Vendeur de mouchoirs en papier. Gardiens de parking et laveurs de voiture. Mendiants. etc.

[Filmer les gestes des « petits métiers »:

Le vendeur de figue de Barbarie

– le geste du couteau qui découpe le fruit

– le geste de la main du vendeur qui tend le fruit au mangeur

– le geste du mangeur qui prend le fruit pour le mettre dans sa bouche

Créer une mémoire des gestes du travail

La rue dans la Médina n’a pas de seuil : pas de trottoirs, pas de passages piétons, pas de pistes cyclables qui hiérarchisent la position des corps.

On a affaire à une bordure entre les deux modes de présence dans la rue tellement les corps du commerce et de la circulation se frôlent, s’entrecroisent et s’entremêlent. Un pas de côté ou une hésitation vous fait passer de corps-circulant à corps-commerce.

Notes sur la circulation

Une impression de chaos ressort de l’observation de la circulation de la rue.

Il n’y a pas de code de la route (ou il n’est pas respecté). Chacun va où il veut, là où son véhicule le lui permet. Chacun traverse la rue là où il le souhaite.

Le flux de la circulation s’organise par le bon sens : le piéton par exemple, doit tenir sa gauche ou sa droite (selon le sens de son déplacement) en marchant au plus près des murs ou des étales des marchands pour libérer la partie centrale de la rue aux véhicules à moteur.

La circulation à moteur se gère à coup de klaxon. C’est un langage codé que seul un marocain comprend. Il y a des coups de klaxon sympathiques et des coups de klaxons antipathiques.

Le klaxon est un moyen d’entrer en communication avec les autres usagers de la rue. Il permet de se signaler avant toute chose.

Piétons :

Les marocains marchent, sans cesse. Ce sont des piétons.

Même dans la suburbia ils marchent !

Moyens de transport des marchandises :

Pour transporter des marchandises, les marocains ont recours à :

– des camions

– des voitures

– des deux roues

– des deux roues équipés en pick-up

– des ânes tirant des charrettes

– des ânes portant des colis sur le dos

– des hommes poussant ou tirant des charrettes à bras

– des hommes portant des colis à bout de bras ou sur la tête.

La rue dans les grande villes :

A Casablanca, Rabat ou Tanger, il y a des trottoirs, des feux de circulation et des passages piétons. Mais comme dans la Médina de Marrakech, les seuils de passage ne sont pas respectés. Les piétons traversent au milieu de la route.

Notes sur un art de et dans l’espace public

Il n’y a pas d’art dans l’espace public des villes marocaines.

Pas de sculptures monumentales sur les places. Pas ou très peu de tags et de fresques murales (street art).

Ceci s’explique par :

– une absence de politique artistique publique de la part de l’Etat marocain (l’art dans son ensemble repose sur le mécénat privé et les aides aux développements internationales). Il n’y a pas de programme marocain pour un art public.

– une volonté de contrôle des formes et des corps dans l’espace public par l’Etat marocain.

contrôle des corps : la grande mosquée Hassan 2 a été construite en lieu et place de la piscine municipale de Casablanca.

Il est plus ou moins interdit, pour un citoyen marocain (voire un occidental), de prendre une photographie ou de filmer dans la rue. Comme il est interdit d’organiser un regroupement ou une manifestation spontanée sans autorisation.

Léa Morin et Mahomed Fariji, fondateurs de L’Atelier de l’Observatoire basé à Casablanca et initiateurs du Musée Collectif (musée citoyen de la mémoire marocaine) insiste sur la question de la négociation. Tout artiste qui veut organiser une action, un happening, une performance ou une installation dans la rue doit passer par la négociation avec les nombreux agents responsables de l’ordre public.

Une jeune génération travaille malgré ce contexte sur les questions que soulève l’art qui s’expose dans l’art public : démocratisation et éducation aux formes artistiques, politisation de l’espace commun, implication des publics dans la création des œuvres.

Malgré leur efforts, cette scène artistique a du mal à émerger.

Notes sur l’espace public comme “agora”

L’espace public, comme lieu de l’agora, lieu du commun où s’expriment les opinions politiques et civiles de chacun, et où s’exposent les formes de création contemporaines, tel que nous pouvons le connaître dans nos démocraties occidentales, n’existe pas au Maroc.

A cause du contrôle exercé par l’Etat (délation), l’opinion publique marocaine ne s’exprime pas dans l’espace du dehors (terme préféré à celui d’espace public).

L’opinion marocaine s’exprime dans les espaces intérieurs et dans l’intimité : à l’intérieur d’un taxi si vous êtes seul avec le chauffeur, ou à l’intérieur d’un Riad, par exemple.

Un nouvel espace public émerge dans le cyber-espace.

Internet, avec la pratique du blog, devient le lieu de l’espace public de la société marocaine : le lieu où l’opinion sur la politique de l’Etat s’exprime le plus.

—————————————-

Laurent Courtens – Privé de public: Quelques réflexions à partir de l’emprise des capitaux privés sur l’initiative artistique au Maroc par Laurent Courtens (L’Iselp)

Lors du séjour au Maroc intitulé Morocco Intersections, est apparu très vite que la quasi entièreté des projets artistiques dans le pays relevaient d’initiatives privées, qu’il s’agisse de particuliers, souvent européens, s’engageant dans la mise sur pied de résidences et de programmes d’exposition (Le 18 à Marrakech, Le Cube ou L’Appartement 22 à Rabat…) ; d’investissements directs de grandes entreprises dans des institutions (le Musée d’art contemporain africain Al Maaden, le programme de résidences Dar Al Ma’mûn, celui-ci étant cependant plus hybride et surtout plus obscur) ou d’engagements plus convenus émanant du marché de l’art (Voice Gallery ou Galerie 127, Marrakech ; Kulte Gallery, Rabat ; Le Comptoir des Mines, Marrakech, émanant d’une salle de ventes).

Dans ce paysage, le musée Mohammed VI à Rabat n’est que l’expression ultime de cette configuration, le roi se posant comme mécène suprême, modélisant les comportements esthétiques des édiles nationaux.

Cette situation a provoqué de nombreuses discussions au sein de la délégation, comme avec nos interlocuteurs sur place.

Ces discussions partaient du constat suivant : s’il y a déficit de l’initiative publique, il faut bien qu’il y ait un supplétif, à savoir l’engagement d’initiatives privées, celles-ci étant perçues comme désintéressées, naïves peut-être, mais en tout cas bienveillantes, positives, « curatives », portées par le désir d’amener de la culture au pays, élan supposé nourrir l’essor du territoire par « l’ouverture au progrès ». Dans le même temps il est signifié que le modèle de « l’état providence » n’a pas vocation à l’universel et que, dès lors, il n’est nul jugement à porter sur des situations où d’autres paradigmes sont à l’œuvre, ceux-ci échappant à l’emprise d’un formatage géographiquement et historiquement très limité, celui de l’Europe occidentale, dominé depuis l’après-guerre par la logique de la subvention publique, dont il est signifié au passage qu’elle est stérilisante, voire asphyxiante. Le privé à l’inverse est « libre », « ne doit rien à personne »…

Par rapport à cette discussion, qui dépasse largement le cadre du territoire marocain, je voudrais juste systématiser un certain nombre de positions qui demeurent à étendre, à étudier et à vérifier. Fondamentalement, elles partent du principe qu’il est un bien public (commun) à édifier, non pas centralement, de manière bureaucratique, à partir des seules prérogatives de l’Etat, mais bien à partir des pratiques artistiques réelles telles qu’elles s’articulent sur les besoins et les réalités vivantes des « gens », de ce qu’il est convenu d’appeler le « peuple », notion aussi vague et multiple qu’essentielle. S’il ne s’agit pas de lui, il ne s’agirait alors que de « l’Art » comme abstraction hors sol, abstraction dont on ne verrait d’autre sens que de se nourrir elle-même, ce qui paraît bien loin de ce que les artistes marocains tentent d’énoncer. De ce point de vue, la rencontre, à Casablanca, avec L’Atelier de l’Observatoire (en particulier sous l’angle du projet de Musée collectif), de même qu’avec l’association Racines, laissent entrevoir d’autres horizons que le simple clivage public / privé versus subventions / mécénat (ou sponsoring, fondations, investissements directs…).

Il faut tout de même à cet égard signifier clairement qu’à mes yeux, ce qu’on nomme « culture » relève du bien public et non de la valorisation narcissique ou commerciale d’initiatives personnelles, encore moins d’entreprises de valorisation symbolique d’actions économiques s’appuyant sur des mécanismes de spoliation.

Je veux dire par là qu’aucun centre d’art, aucun musée, aucune fondation, aucune œuvre de bienfaisance, jamais, ne fera oublier, ni ne comblera, l’abysse d’inégalité brutale qui sévit dans le monde et, en l’espèce, au Maroc.

Et l’un des premiers effets des actions de mécénat ou de sponsoring est de neutraliser, de lisser, de camoufler en somme, les pratiques économiques de trusts industriels et financiers qui aujourd’hui participent activement à l’emprise de l’oligarchie financière sur le monde. Allianz ou La Société Générale (deux groupes croisés au Maroc) appartiennent à ce niveau de pouvoir dont la puissance, l’étendue et le degré de nuisance sociale ne peuvent être minimisés sous couvert de respectabilité culturelle.

Et à vrai dire l’intérêt du « privé » (on nomme ici les grands groupes financiers, pas l’amateur isolé) pour la culture et les arts vise précisément à étendre sa sphère d’influence sous l’insigne de « responsabilité sociale des entreprises ». Celle-ci désigne en fait un projet de société qui cherche à étendre l’influence du Capital sur l’ensemble des activités sociales.

Bruno Caron, président de l’association Art Norac, fondée par le groupe agro-alimentaire Norac, initiatrice de la biennale « Les Ateliers de Rennes », l’indique comme suit : « L’Entreprise (…) entretient des relations directes avec ses fournisseurs et ses clients, tisse quantité de liens avec son environnement territorial, culturel, administratif et développe ainsi une grande expérience de l’organisation collective et des relations entre les personnes. Mais paradoxalement, à un moment où l’Entreprise n’a jamais été aussi importante dans son rôle économique et financier, sa participation à la vie de la cité n’a jamais été aussi faible et est finalement peu présente dans la Sphère Sociale » (1).

D’où l’investissement direct de quantité de sociétés dans des opérations caritatives, campagnes médicales, travaux de recherche scientifique ou initiatives culturelles.

Dans cette perspective, la « culture » procure un capital symbolique augmenté, mais aussi active la créativité et la recherche, indispensables aux développements des entreprises dans une société dite de la connaissance sous très haute tension concurrentielle. Ecrasée dans les entreprises elle-même, la créativité fleurit comme valeur suprême dans les discours officiels, la communication, la construction symbolique des « marques » (2).

Un autre espace public

De ce point de vue, il faut encore préciser deux choses :

- Ce modèle néolibéral n’est nullement une invention marocaine, ni turkmène, ni chinoise. Elle a été élaborée en Europe et aux Etats-Unis, dans les années 1970, au cœur des thinks-tanks dont les thèses ont ouvertement et brutalement mis la main sur le « monde libre » à partir des années 1980 et, plus encore, depuis la chute du mur. Il n’est donc pas exact d’opposer un « modèle » marocain authentique au schéma eurocentriste que serait l’Etat-Providence. Ce serait un comble de recourir aux héritages postcolonialiste et au différentialisme culturel pour motiver l’emprise néolibérale sur la société marocaine, celle-ci demeurant du reste (et de longue date) sous forte influence française, l’un des acteurs culturels majeurs demeurant… l’Institut français.

- Ce modèle — en pleine expansion planétaire — ne prétend pas se défaire totalement des institutions politiques (en tout cas dans les zones stables telles que l’Europe elle-même et, nous semble-t-il, la plupart des pays du Maghreb et du Machrek). Il aime les pouvoirs « forts » aptes à contraindre les populations, à les mobiliser, à imposer sous couvert de consensus les options politiques de la dérégulation, des privatisations… Au besoin, il lui faudra passer par la force, la répression, la violence déclarée, l’armée. C’est pourquoi, au Maroc, il aime la monarchie, sa puissance, sa capacité d’influence, sa dimension rassembleuse, mobilisatrice….

La monarchie, précisément, a puissamment contribué, durant les années de plomb, à l’évidemment de l’espace public, à son lissage et à son uniformisation. Les changements actuels vont vers plus « d’ouverture », accompagnée d’un complet désengagement (sauf par voie d’influence et de contrôle).

Face à ce double vide, ce que je pressens comme possibilité n’est pas la culture subventionnée par une bureaucratie centralisée (éventuellement corrompue, statufiée, pétrifiée….), mais l’élaboration d’un nouvel espace démocratique où la culture s’inscrit dans des mécanismes d’émancipation collective.

A cet égard, j’ai été marqué par deux expériences :

- Le Musée collectif de Casablanca animé par l’Atelier de l’Observatoire. Là, collectes d’objets, de témoignages, de paroles, de documents, d’archives édifient progressivement des identités multiples et une mémoire collective de la ville. Des sutures réelles opérées sur des lieux délaissés (parcs publics tel le parc Yasmina, cinémas, stades,…) ainsi que des restaurations et des réactivations d’objets dans l’espace public (par exemple les manèges abandonnés d’un parc d’attraction) instituent un devenir vivant et commun sur le territoire de la ville même.

- L’association RACINES a pour slogan « La culture est la solution » (en opposition aux courants islamistes affirmant « l’islam est la solution »). Solution à quoi ? Aux problèmes démocratiques, aux injustices, aux dénis de l’espace public, à la phallocratie , au machisme. Bref à des problèmes politiques. RACINES en ce sens peut être assimilé au secteur de l’éducation populaire (dite permanente en Belgique). L’association travaille sur trois axes visant le développement humain et social : émancipation, redevabilité (reddition des comptes : l’Etat doit des comptes en termes de réalisations publiques), solidarité (3).

Dans cet état d’esprit, l’association mobilise des moyens artistiques sur tout le territoire national en vue de travailler sur des questions politiques telles que l’espace public et ses usages, les violences sexuelles, l’éducation nationale… Il s’agit de formes assimilables au théâtre populaire.

Par ailleurs l’association établit un rapport périodique sur les pratiques culturelles au Maroc, de même que sur les besoins du pays.

A l’occasion de notre rencontre, le coordinateur de l’organisation, Aadel Essaadani, nous a indiqué qu’ils faisaient en fait le boulot des pouvoirs publics, absolument démissionnaires de ce point de vue là. Les conclusions de ces rapports sont par ailleurs à considérer comme des recommandations politiques. Dès lors qu’elles ne sont ni entendues ni appliquées, elles prennent force de plaidoyer ou de cahier de revendications.

Cette articulation, aux yeux d’Aadel Essaadani, pourrait bien être la préfiguration tout à fait involontaire d’une relation possible entre culture et pouvoirs publics : celle où l’action culturelle, en lien avec la population, établit son devenir et ses outils critiques indépendamment de l’emprise publique, mais en vue d’agir sur les mécanismes démocratiques. Encore faudrait-il imaginer, dans cette perspective, un authentique devenir démocratique apte à intégrer les démarches culturelles comme leviers critiques et outils de contrôle populaire.

C’était la voie ouverte en France, au sortir de la guerre, avec la direction de l’éducation populaire (intégrée au ministère de l’éducation nationale) dans la perspective d’une éducation POLITIQUE des jeunes adultes. C’est le pouvoir gaulliste qui, à la fin des années 1950, a démobilisé cette direction pour la convertir en « ministère de la culture », construit sur une conception nationale et élitiste de la culture (le « génie français »), réduisant la culture à la seule pratique des « arts et des lettres ». C’est en fait là la source des pratiques centralisées et bureaucratisées du soutien public. Ce qui a été oublié dans l’intervalle, c’est une autre conception de la culture inscrite au cœur de l’activation d’un espace public à haute teneur démocratique (4).

Pistes de réflexion établies suite au voyage d’étude Morocco Intersections, Flanders Institute (en collaboration avec Wallonie-Bruxelles International et la Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles), 24–29.09 2017, Marrakech-Casablanca-Rabat.

Notes:

(1) Les Ateliers de Rennes — biennale d’art contemporain. Un nouvel événement incontournable ! Valeurs croisées, 2008, dossier de presse, Rennes, 2008, s.p.

(2) J’avais en partie systématisé cette analyse, à partir du cas d’Istanbul, dans le cadre d’un colloque organisé à l’ISELP en 2010, su rle thème des frontières. Voir Laurent Courtens, “La 11e biennale d’Istanbul: Brecht au bal des nantis”, in Aborder les bordures. L’art contemporain et la question des frontières, ISELP / La Lettre Volée, Bruxelles, 2014, pp. 47–63. L’approche du cas marocain exigerait une étude au moins aussi précise.

(3) voir e.a. Racines, FADAE (Free ACCES and Diversity for All and Everyone), Manifeste pour l’espace public au Maroc, Casablanca, janvier 2017

(4) Voir Franck Lepage, “De l’éducation populaire à l’éducation par la culture”, in Le Monde Diplomatique, mai 2009, et, du même auteur, L’éducation populaire, Monsieur, ils n’en ont pas voulu…, Editions du Cerisier, Cuesmes, 2007