History and Science Fiction of Performing Arts Networking (1981-2068)

Discussing international networking with Kee Hong Low at Producer’s Network Meeting and Forum, West Kowloon Culture District, Hong Kong, 5 May 2016

Lecturing at the Producers Network Meeting and Forum (West Kowloon Cultural District, Hong Kong, May 2016)

‘Way to go, you’ll be amazed! The energy and drive in this Asian network really reminds me of the dynamics in Flanders and Europe in the eighties.’

That’s what my colleague Hilde Teuchies said to me late 2015, when she heard I was invited at the Producers Network Meeting & Forum, organized by West Kowloon Cultural District in Hong Kong, to talk about the development of international networks in Europe.

I was really thrilled when I heard this, because Hilde really knows what she’s talking about. In the eighties — that mythical era for the contemporary performing arts — she was the first coordinator and Secretary General of IETM, the international network for contemporary performing arts. Hilde is part of a gifted generation of cultural entrepreneurs, festival directors and cultural networkers par excellence whichdeeply transformed the performing arts scene in Flanders and Europe through international collaboration. After meeting this group of Asian ‘creative producers’ at a meeting in Melbourne in 2014, she was energized. She added:

‘There’s something special going in Asia right now. These people are building new networks and opportunities for artists from scratch. They want to learn from us, but in Europe today, we can learn a lot more: from their optimism, drive and energy in sometimes difficult circumstances.

And indeed, I was inspired. On the website of Flanders Arts Institute, I already shared extensively my light bulb moments at that meeting — about the developments in cultural infrastructure & new performing arts venues in Hong Kong, Taiwan, mainland China, about developments in cultural policy making and international networking. And of course, I met all these amazing people in person. You can learn all about it here.

Next month, the next and third edition of PNMF will take place in Hong Kong. Sadly, I can’t join — but that sentiment is not the only thing I wanted to share in this post… In order to nourish the debates, the generous people at West Kowloon Cultural District, made a transcript of my lecture and the discussion I had with moderator Kee Hong Low (Head of Theatre at WKCD) and the audience.

I already posted the slides of this presentation earlier. Now you can read the whole transcript here below. It’s a very, very long read, but I thought it would be nice to share the text, because the lecture tries to answer a question we get a lot at Flanders Arts Institute.

How to explain this ‘Flemish Miracle’ in the performing arts, the fact that such a small community in such a short timeframe generated so many extraordinary talents? Is it the result of innovative policy making? What is the role of international networking? Can other countries learn from what happened there and then?

This would be a great topic for more in depth research and reflection — which up until today is lacking. In the meantime, the following ideas and provocations might provide an outline, if you have 26 mins to spare.

研討3:

塑造與被塑造:藝術製作的網絡

──八十年代至今法蘭德斯和歐洲的表演藝術集體策略

主持:劉祺豐 Low Kee Hong(香港)

講者:約里斯.簡森斯 Joris Janssens (布魯塞爾)

Intro

Janssens: The first couple of days of this conference have been very inspiring. I like the energy in this network. You are a group of very dynamic people wanting to exchange experiences concerning the performing arts in Asia. You also want to give this exchange a structural basis. In this context, we can learn a lot from each other. I was invited share some experiences we had in Flanders and Europe since the 1980s. Back then, we saw a similar energy. What I want to share today, is how this energy helped to shape an ecosystem for contemporary performing arts in Flanders and Europe. But I will also explain how current trends in a changing, increasingly global environment are fundamentally challenging the way we work. What answers will we come up with? If we exchange about that, we can learn a lot from each other.

To nourish the discussion, I was asked by Kee Hong look into the case of IETM, the International Network for Contemporary Performing Arts. I will tell you about the genesis of this network and how it has developed since the 1980s. I will also focus on the interrelation of this European network with the developments in Flanders, a small region in Europe. What is the impact of international networking on the development of a local scene? Kee Hong also stresses that your network is really about the development of concrete actions. So I will also try to inspire the further development of your network with concrete topics for discussion.

About Flanders Arts Institute

First, let me tell you something about myself. I work as head of research at Flanders Arts Institute. Flanders Arts Initiative is a recent initiative. It started in 2015 with the merger of the Flemish Theatre Institute (VTi, which was the institute for performing arts), BAM (Flemish Institute for Visual, Audiovisual and Media Art) and Flanders Music Centre. So now we are working in all the different art disciplines. We are an information portal and we do research and development activities about different topics, in order to support the development of the arts field. How can the field be organized in the future, how can cultural policy develop? We do this in a Flemish context but also internationally. It is in our mission to help the field in its development of international relations.

For the topic of today, it is interesting to point out that our history goes way back. The Flemish Theatre Institute, one of our founding organisations, was started in the 1980s. It was very much connected to the developments which I will talk to you about today. In fact, VTi started in the early 1980s as a touring circuit of alternative venues and festivals popping up in different Flemish cities. These functioned as a new platform for producing and presenting the work of emerging artists. Setting up a touring circuit among these new venues was the origin of our institute. And the additional functions that we took on later — the documentation, the research, the policy observation, and all kinds of services to support the development of artistic practices — always started from one and the same intention: to set up collaborations to create a more balanced ecosystem for contemporary performing arts in Flanders.

So, to make my position clear, I do not work at the IETM bureau, but I have some relevant experience. I have been taking part in IETM meetings for the last ten years. And it is also relevant to point out that the links between our Institute and IETM go back to the early eighties. VTi has always been very much supporting the development of international collaboration. The IETM started in 1981. And in fact, the VTi office in Brussels was the first place where the bureau of IETM was organized.

This talk has three chapters. First, I will introduce the IETM. Next to some founding myths and wild stories about the early days, I will explain how it functions today: how is the membership constructed, what is the geographic scope, how do they organize the activities, etc. Second, we will talk about the impact of international networking on the developments in Flanders since in the 1980s. I will also share some research material about trends in international touring and coproduction. Third, we will reflect about the future, about the changing context for international networks. At this moment, there is a lot of pressure on international collaboration in Europe. This calls for a response from international networks, both in Europe and in Asia.

About IETM today

IETM is a membership organization with a mission to stimulate the quality and the development of contemporary performing arts. In 2015, there were 532 active members coming from all the performing arts disciplines (theatre, music theatre, dance and circus). The type of partners is very diverse: companies, venues, festivals, producers, next to research or documentation centers, agencies,…. Funding bodies, such as art councils, are also present. But they have a different status — they are called ‘associate members’. So, in general, the IETM membership covers all the functions which are relevant for the performing arts ecosystem. At this moment, almost 9 out of 10 of our partners come from Europe, but there is an increasing number of partners from other continents.

The Plenary Meetings — one in Spring, one in Fall — have been the backbone of the network since the early days, up till now. As you know, IETM has also been organizing smaller meetings outside of Europe, to discuss issues of collaboration and connect to local artistic scenes. Some of you were present at the Satellite meeting in Gwangju (2015), and at the Caravan meeting in Seoul (which was more like an exploration trip where you visit certain places).

The live meetings are the most important, but also other formats for exchanging information have been developed. Also on the IETM website, you can propose projects, share ideas, research and other resources. IETM also plays an active role in raising awareness about the value of the arts with different stakeholders in European policies.

Strong stories about the early days of international networking…

‘So that is the IETM today. Now I will be talking about the history of the network. In fact, it will be striking that in the early days, IETM was quite a different network. Originally, IETM was short for “Informal European Theatre Meeting”. It used to be informal but it is not anymore. It used to be European but it is not anymore. It used to be about theatre but this is broader now (performing arts). But it is still about meeting.

A couple years ago they changed their baseline: they kept IETM as the brand name but now it is short for “International Network for Contemporary Performing Arts”. This is more close to what the network is about today.

It all started in the summer of 1981, in Polverigi, Italy. This is a really small town which had a contemporary performing arts festival. The idea of the IETM was born in a nice villa on one summer night in the infamous Villa Nappi, with some glasses of wine, some pizzas and a lot of cigarettes.

It was in the context of Inteatro Festival which was founded in 1977 by Roberto Cimetta, an Italian theatre director. Cimetta had gone to the Mayor of Polverigi and asked if he could use this villa to organize a festival. That was ok. He also held residency for artists to come there, providing all kinds of support for the local scene. And in the festival, he also invited his international colleagues. Because there were a number of alternative festivals popping up at that moment, these people wanted to meet with each other. On a certain summer night in 1981, they conceived the idea of organizing regular meetings to talk about the development of their different projects. So the first real IETM meeting was held in the Fall of 1981 in Paris. It was organized by ONDA, the organization supporting the distribution of international performing arts in France. There were already some more people there.

Here you see a fake infographic giving you an idea about the myths concerning these early days. Rumour has it that there were only 10 people on that summer evening in Polverigi and — let’s say — 30 people at this first real IETM meeting in Paris. But you can find almost 100 people who would claim they were part of these legendary meetings… This is illustrative of the vibe, the energy and the dynamic at the time…

So why was the network so successful, at that moment within that context? One important thing to point out is official international collaboration was very much driven by governmental organizations. There was a need for non-government driven connections. Second, the performing arts landscape at that moment was dominated by the large international festivals which had existed since the 1950’s. But at the same time, a lot of new alternative and not well-funded festivals were being put up by people such as Roberta Cimetta. You could call them cultural entrepreneurs, although they themselves would never use that term… In any case, these were a number of really gifted and involved people, setting up festivals but also doing other things to support the work of artists. Some of these people set up producing organizations and started lobbying with cultural policy makers.

Third, there was still segregation after the Second World War between the Western and the Eastern parts of Europe. It was quite difficult to work across the so-called “iron curtain”. Therefore, people needed networks in order to create a more equal space for cultural exchange in Europe.

And fourth, what’s more, these were the days before Facebook, Youtube or DVDs… So the first thing these festival directors wanted to share is information about artists: who are the good artists, what is interesting work? In the early days, IETM was really about detecting talent. This was the first thing people wanted to share. But they also exchanged practical knowhow: how to set up a festival, practical issues with international mobility and cultural policies. People exchanged arguments to develop policies for contemporary performing arts, which was quite exceptional at the time in Europe.

Maybe it is interesting to point out that, at that moment, only festival directors could be member of IETM. They talked about the artists, but they were not allowed to be there. This only changed in the nineties and it changed the network drastically. And another major change: at first the set up was very informal. Someone who volunteered to organize one of these meetings could do that. It was only after 8 or 9 years that the structure was really formalized, as an association under Belgian law.

The ‘Flemish Miracle’

I will come back to these changes of the network later in this talk. First, let me tell you more about how this development of international networking resonated with the development of the local performing arts scene in Flanders.

Flanders is the northern part of Belgium, the Dutch-speaking region. It is very small, with only 6 million people, but it has developed a really exceptional artistic energy since the 1980s. Since then, in Flanders and Brussels, a number of gifted artists started to work who today are playing the most prestigious stages worldwide. You might know of works of Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, Jan Fabre, Ultima Vez, Alain Platel and others, and the many artists since then who joined the Flemish scene.

These household names started all in the timeframe of 10 years. This is really exceptional. At Flanders Arts Institute, we are often asked how come such a small country could produce such a great number of talents in a short period. Sometimes people think this is the result of a developed policy for contemporary performing arts. But this is not the case. Actually, at that moment, there was no policy for performing arts.

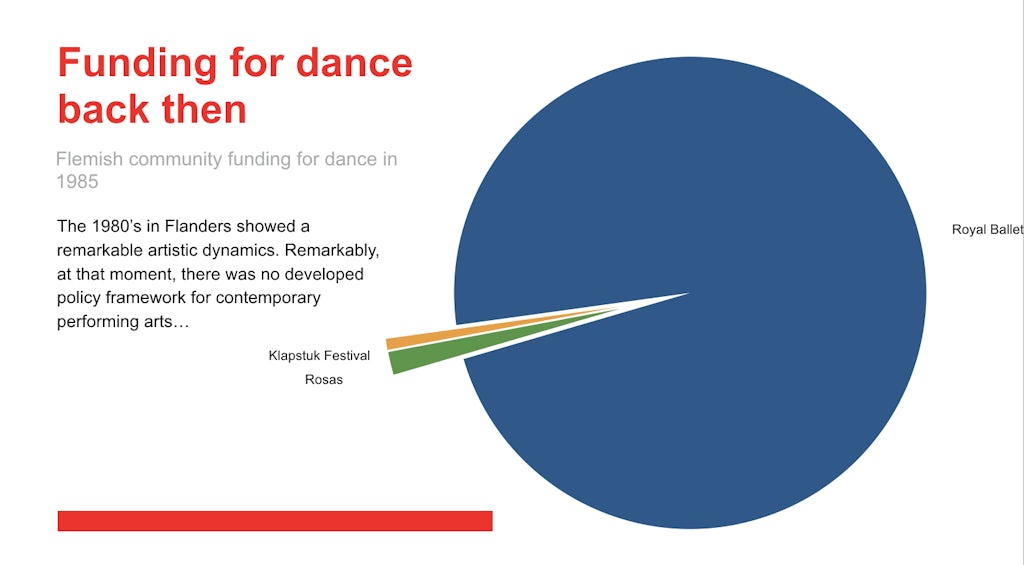

This is a graph illustrating the funding for dance in Flanders in 1985. 98% of the budget went to the Royal Ballet, 2% went to a company (Rosas) and a festival (Klapstuk). Back then, the funding for contemporary dance was peanuts.

But how did this remarkable artistic vibe come about then? It is really important to stress that this is really about the bottom-up development of the field. This was no accident. There were a number of collective strategies be used by cultural entrepreneurs working together to support the work of these emerging artists. I will present an overview of a number of initiatives, which might be relevant for discussions here and now and later.

The most striking thing is in fact all the functions in the ecosystems were tackled collectively. First: producing. The artists mentioned before only in a later stage start their own companies. They started first with mutualizing their resources in collective structures. A good example was the non-profit Schaamte (literally: ‘Shame’), which supported the work of a.o. Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker and Jan Lauwers. Also Les Ballets C de la B, Alain Platel’s structure, was and still is a collective company. These producing organizations had interesting solidarity mechanisms: one artist’s income from touring was invested into the production of the other artist. So it was a solidarity mechanism for production of the work.

Second, co-production and presentation. I have already told you about alternative festivals popping up. But in different Flemish cities alternative venues were set up. Vooruit (Ghent) for instance started as an alternative venue in the early 80s without support from the government.

Low: And actually the context of why there were these artist-run-collective organizations or even these co-production organizations, was because there were abandoned spaces in 1980s in Belgium. The artist just came in and occupied the spaces, so literally they had a roof over their heads for nothing. This allowed a lot of these organizations to exist. Without space, it would be impossible for artists like Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker to create work. That was the context.

Janssens: Indeed, we are talking about abandoned garages, cinemas, buildings of political parties and university buildings. Every space that could be used, was used.

These new venues also worked together to coproduce and present. I have already explained that the Flemish Theatre Institute started as a touring circuit of these alternative venues. We also took initiatives to promote the works of the artists internationally.

And that is where the international networks came in. I told you that the IETM meetings really were about exchange of information. But it also led to co-production, at a moment in time when there was almost no funding in Flanders. Especially the Théâtre de la Ville in Paris was important. In the 1980s and 1990s, they might have invested more in our artists than the Flemish government at that moment…

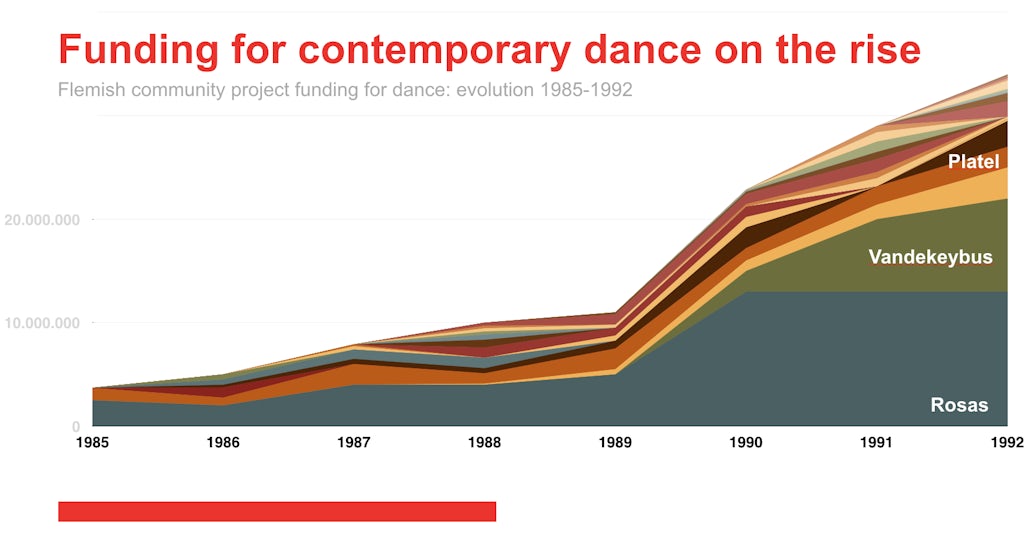

Lobbying was also tackled. The Flemish artists really used their international success to gain support from local policy makers. How did the Flemish policy makers react to this? They picked up the energy. Before I have shown you the graph with the funding of dance in 1985. The graph below shows the developments from 1985–1992 (only showing the funding for contemporary dance, so not the Royal Ballet).

By the start of the nineties, the budget for contemporary dance had almost tripled. There were a lot of new companies being supported. But more importantly, it was not only about the money. Also the laws were changed. In the eighties we only had a Theatre Decree (a decree is a Flemish law), which allowed theatre companies to be supported, but only for one year. The new Performing Arts Decree of 1993 was the result of this new vibe in the contemporary performing arts. That was a significant shift.

The new law opened up to these alternative spaces, the arts centers. It also opened up to dance and music theatre companies. And, very important, it allowed multi-annual funding, for four year periods. The philosophy of the law was its open and bottom-up approach. Anyone could — and still can — apply for funding for an artistic project, without a lot of qualitative or quantitative restrictions or directions. Your idea will be evaluated by peers on the basis of artistic criteria, to see if you get money or not. So it is really something quite crucial: the system is quite open and this allows for artistic innovation and risk taking.

Low: I am quite curious about the policy makers. Did they just observe the growth of the scene and respond? Or was there a lot of lobbying, telling them to look at this change, therefore they start the motion of thinking?

Janssens: It is a combination of different elements. They observed what was happening and lobbying was also important. But one extra element is quite crucial: the state reform of Belgium provided the right political context. In 1980 the Flemish Community had gained political autonomy: it had its own parliament and government. The new-born nation-state wanted to assert its autonomy of by investing in arts and culture. Flanders wanted to brand itself as a new, young and liberal nation which invested in different kinds of innovation. There was a lot of investment in technology at that moment, but also in the arts. A young culture minister was really interested in the developments in the performing arts. It resonated with the political dynamics at that time. This is an important element why it was picked up.

Now I will present to you a number graphs from our current research, about trends in international collaboration. These are based on the information our colleagues at the Flanders Arts Institute gather about Flemish productions, about where they toured and about the organisations producing the work. You can consult the data via http://data.kunsten.be. I already indicated that, since the 1980s, international collaboration is really important for the development of contemporary theatre. What we see in a number of slides, is that there is a lot of pressure on international collaboration.

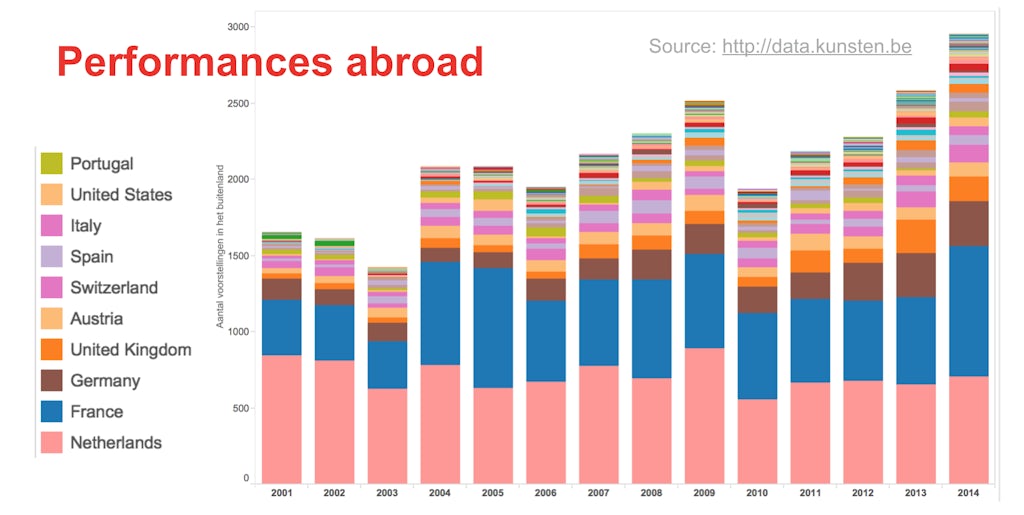

The first graph is about the international touring of Flemish production since 2001.

For each year, you see the number of shows abroad. International touring has expanded quite a lot in last 15 years. More productions have toured abroad. You will also notice that shows in the different countries are displayed in different colours. The countries in which the performances were shown, have changed. Half of the performances abroad in 2001 were shown in Netherlands. In 2014, the Dutch share has dropped to 22%. The share of France increased. And the number of countries where it has been played actually doubled (from 30 to 60). So you see the internationalization and also globalization of international touring from Flanders.

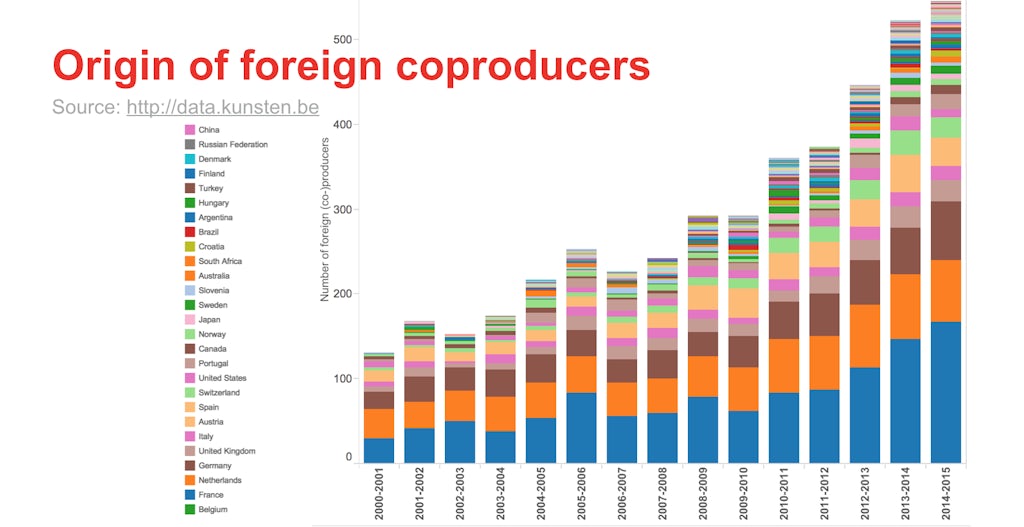

Second, working internationally is not only about touring. It is also but about co-production, that has risen even more spectacularly. This next graph shows the number of foreign co-producers involved in the production of Flemish work from 2000 to 2014.

As you see, in 2000, there were 135 foreign co-producers working with Flemish companies. Now it is four times more, it is 545. I think this raises a number of questions.

Low: Just a quick question, can you clarify what is considered as foreign co-producer? What is the definition of foreign?

Janssens: Foreign means: not from Belgium. You see the background and origin of foreign co-producers. You see neighboring countries are important. Especially France, but also partners from all over the world.

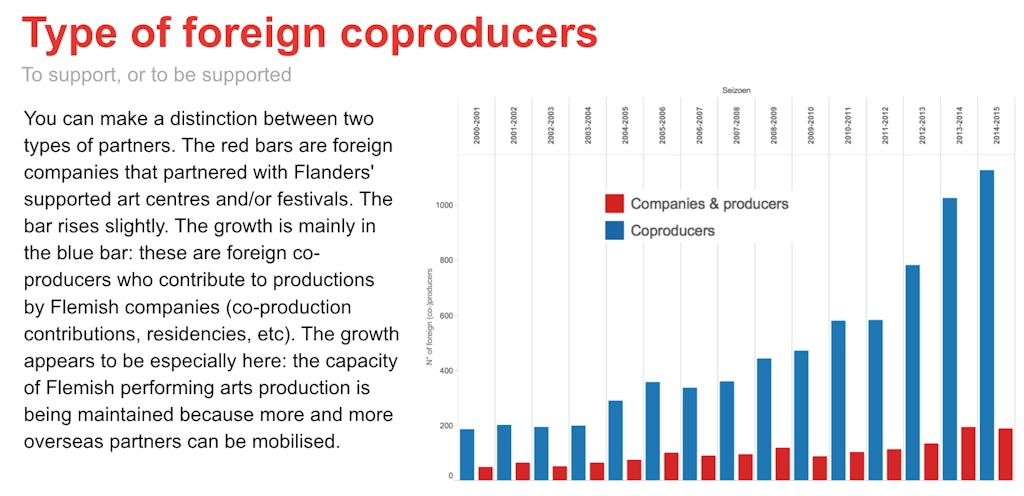

You can also look at the functions of these co-producing partners. This graph distinguishes between two kinds of relationships.

In red, we see Flemish venues and festivals investing in the work of international artists. This has been increasing. But mostly, in blue, it is about international venues investing in the work of Flemish companies and Flemish artists. So international collaboration for the Flemish goes in two directions. Indeed, it is about supporting international artists. But it still mainly is about finding resources abroad to be able to make productions.

You can see the bars are growing very fast. You must keep in mind that the number of productions made each year is stable. So the increasing number of coproducers indicates that you actually need more and more partners in order to keep up with the same level of production. You need to expand the network, or you fail.

This trend is most likely related to drops in government funding. In a lot of European countries, governments are stepping back. The purchasing power of organizations decreases. All these organizations are increasingly more vulnerable. Their budget for production is a lot less than it used to be, and they do not want to produce less. So they need to engage more and more partners and expand the network. This is quite worrying. There is a lot of stress on international collaboration in Europe at this moment.

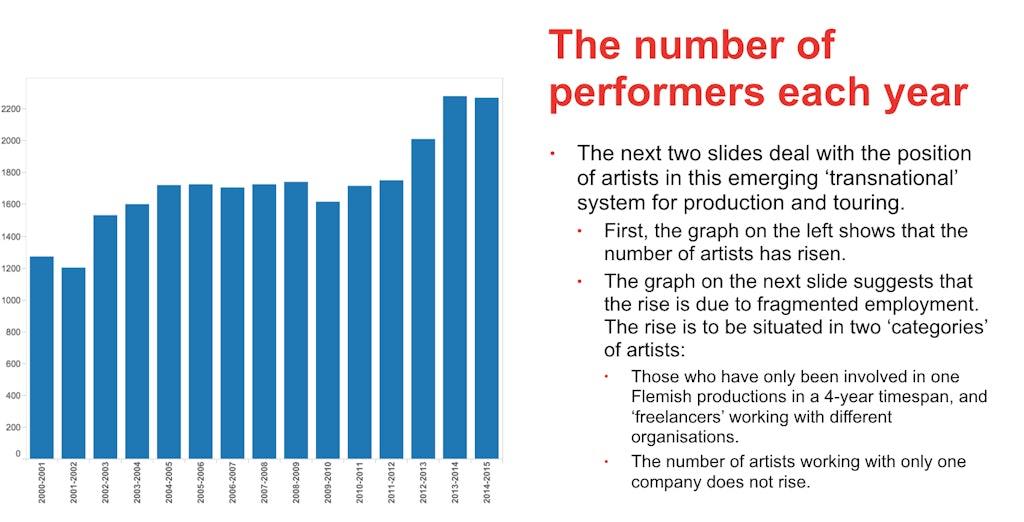

I have two last graphs that tells you something about the position of individual artist in this transnational system of touring and transnational presentation.

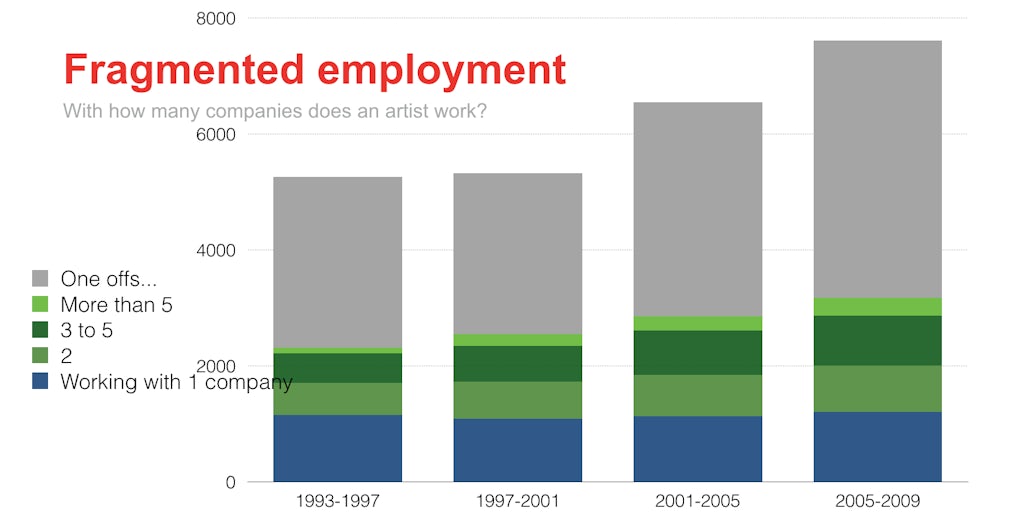

First, you see the bars on the first graph are becoming bigger. This means that there are more artists working in performing arts in a four-year period.

The colours on the second graph tell you something about how the artists work. With how many companies do they work together in a four-year period? You can distinguish between artists with more or less fixed employment (one employer only in four years) or freelancers working with different producers. And we have one special category: the grey bars are the ‘one-off’ artists. These are artists which we see only once in our database in a four-year period. They are not structurally active in the Flemish performing arts.

The blue bar is the category of artists making multiple productions within the context of one company. So this is about fixed employment of artists. In this category, there is no rise at all. We see a rise in two segments: the freelancers / job hoppers, and these ‘one-offs’. This suggests that today, there is less sustainable employment in the field of performing arts.

Low: But for the rise of freelancers and one-offs, is it because there are more and more mobile artists who are arriving in Belgium, based in Belgium and circulating around the region that created this scenario? Or was it a natural growth of artists from Flanders?

Janssens: It is both. Different trends can explain this. International mobility certainly is a driver. And also the fact that there is more interdisciplinary work. So there are lots of musicians there, audiovisual artists, visual artists, … doing ‘something’ in the performing arts on a project basis and going back to what they do in their work outside of performing arts… But it is not always a choice. In fact, a lot of artists do not have enough arts projects. So they teach, they work in cafes, … The idea of multiple job holding is also an element.

So it is a combination of different trends. But the main issue is that the employment in the performing arts is becoming less stable and more fragmented. This raises the question of sustainable development of artists’ careers. A lot of flexibility is needed if you want to survive in this kind of landscape. I think this is a major challenge for everyone who is involved in this ecosystem at this moment: the working conditions for artists have been under increasing pressure the last years.

Some conclusions

To summarize, we have demonstrated and illustrated shifting practices in the performing arts. Back in the days, you most likely were part of the company. You made a production each year. You went on tour; you came back home. If it was successful, then you had a rerun. If not, you made a new production. It was all pretty clear, but now the prototype has changed. There is more project-based work, initiated by producing organizations working with freelancers from different countries, from different disciplines. Sometimes a transnational network of presenters also invests in the production.

So the types of relationships (between artists, between organizations) have changed fundamentally. And this is because of international networking. This is because of the policy supporting this kind of work. These are important drivers behind this shift in the practice.

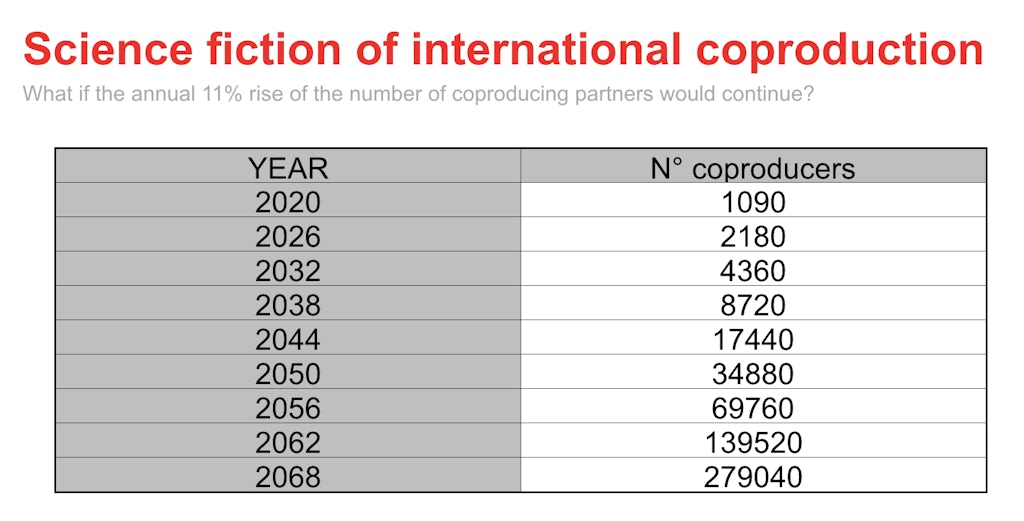

We see that this has resulted in growth: more productions, more artists, more international touring, more co-productions, but less funding. And this is really worrying. Because how sustainable is this growth, if you need 11% more co-producers each year? The number of co-producers needed to maintain the production capacity doubled each 6,15 years. That is why we made this little science fiction of international co-producers, just to see what would happen if it continues to grow at the same pace…

So in 2020 we would already need more than 1.000 international co-producers, and in 2068 we would need 280.000 to keep up the same level of production… This seems funny but there are really smart people who have very strong ideas about the fact that exponential growth is not sustainable. For instance, think about the development of global population: if it continues in let’s say, 50 years, is this sustainable for this planet? This kind of reasoning makes sense. We cannot continue like that, expanding partnerships because of the economic pressure. We can look at the advantages of this transnational system of co-production, but we must also raise critical questions about sustainability.

Low: This is an interesting point, because I remember last year when we met in meeting, a participant was talking about independent producing scene, he raised a key point that, in the situation in Asia or perhaps at the global level as well, we are actually over-producing. In the sense that we are all in this sort of machine, of course in different contexts. In Asia, with grants in different Asian cities, they propel you to make more works in order to survive, without really clarifying the impact of this overproduction on touring. In fact in Asia, when the work is made, it goes for a first run, and most of the time it stops there, and unless you are lucky then you get second and third run. I know from a previous graph there are works from Flanders, they exist for 10 to 15 years, and they still keep touring. Here things are very short. So of course this impacts resources. But also as Cheung Fai yesterday said, money is never enough, and even in China resources are big. But it also raises the question whether we want to be responsible as well and to look at this impossible growth situation.

Janssens: Yes, the last few days we have talked about making the lifespan of productions longer. This is also an issue we really want to promote in Flanders. In fact, we can learn a lot from the modes of producing deployed by the international touring companies. Their whole organization is in tune with this system. Immediately when a production is being made, they make sure they will be able to tour for a long time. From the start, it has been taken into account that they have different language versions, they have multiple casts, the scenography is not too complicated, there is no discussion about rights etc. When you take this into account while producing the work, the lifespan can continue for quite some time — if the production is a success of course, if you manage to convince new venues to book the show.

Some organizations are really developing a smart way of working, differentiating the productions they make… If you look at their body of work, it can also be a combination of one-off events and also a backbone of success productions that can go on tour for years… I think this is really interesting. It reduces the risk for organizations, since their sustainability is not dependent on the success of their last production.

Low: So meaning for example for Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, they have a backbone of key projects that are meant for touring, but then year on year they would look at smaller events to have the combination, is that what you mean?

Janssens: Yes, but the events can also be quite big, in the sense that there was the big project of last year. Rosas’s Work/Travail/Arbeid was a crossover between an exhibition and a 9-day dance piece in a museum. It has been performed in Paris, Brussels and also New York. So it is really a short ‘tour’ but it is supposed to be short because it is so huge and expensive. But it is as you said, they combine different activities, also small productions which are able to tour over a longer period of time.

Later today we will discuss our ideas about international collaboration and sustainable growth. To start the discussion, I would like to show you two books, one with a positive view on things and the other with a more pessimistic perspective.

Thomas Friedman, the columnist of the New York Times, wrote The World is Flat, a book about the flatness of the world. What does this mean? Friedman stated the world increasingly is a playing field which is being leveled. Internationalization first used to be a matter of nation states (colonizing the world). And then businesses came into play (becoming multinationals). And now individuals can go over the world and collaborate with everyone. In a way, this is also the case for the performing arts. In the figures, we have seen that there are more freelancers and more international collaborations. For artists, it is very good that the number of possible partners to support their work is expanding. There are some opportunities in there, but also some threats.

Richard Sennett has written this interesting book, The Culture of the New Capitalism, asking attention for the negative side effects of this levelling process. He raises critical questions about the working conditions in global capitalism. These questions are relevant for the performing arts too. Because, very similar to these capitalist businesses, also in the performing arts we see a rise of project based work, freelancing, outsourcing and flex work.

What kind of organizational culture does capitalism produce? This is the question asked by Sennett. We from our part must ask the question, if we look at this system, what kind of art will it produce? What are the artistic implications, if you need a growing number of art venues to produce your work? As an artist, if you need to convince them to support your work, you will not only need interesting projects but also the right networks and social skills. Artists who have these networking skills have better chances to survive in this transnational network, compared to others who are just good at making art.

Low: About 10 years ago, I remember the rise of what I call residence junkie artists, those are people who are very good at writing proposals into multiple residencies. So basically in the whole year, they spend time up to 3 months at different residency locations supported with money, space, per diems and all that, without actually making a work. And with that, it created a bubble. You are right in the sense that only a certain type of artists you keep hearing, you keep seeing. But for people who are not that good at writing proposals it is difficult to be selected or even pitched; so they get left behind.

Janssens: This is what is happening and it is striking to see that the trends in arts very much resemble this search for efficiency of global capitalism. This is worrying. But on the other hand you see a lot of interesting experiments with new organizational models. Some artists are really seeing organizational work also part of the artistic work. I think that experiments being done in the artists’ field have larger social value. These experiments can inspire our thinking about new ways of working in the society of the future.

But that is another topic. Right now we are talking about challenges for international networking. We have been talking about the fact that the artists are working in more independent basis. We have been discussing trends in internationalization and globalization. Also digitalization is important: it is quite clear that new technologies also open up opportunities for networking.

Ways forward for international networking…

So these are a number of questions for all networks: for IETM, for you, for others, … In this context, what do you need a network for? And what should it do? Let’s take IETM as a case study once more.

In the early days, the IETM talked about the network as being ‘biodegradable’. People said if the network does not serve its function anymore, we just quit. This is not exactly what has been happening. The IETM did never stop but adapted itself to ever changing conditions. It was kind of like a recycling network. I will show you how the IETM responded to the abovementioned trends and challenges.

First, they expanded the network. The membership has changed. In the early days, there were only festival directors. In 1990 or 1991, it opened up to companies and ten years ago to individual players as well. Now the balance has shifted completely. The majority of the members is companies, artists and producers. The result is that the festival directors have shifted: a lot of them do not come to IETM anymore. They have set up other places to meet, as they are also overwhelmed by all these artists who want to talk to them, who want to convince them the quality of their works. So the knowledge exchange of festival directors is happening on other, more exclusive platforms.

So it means the IETM today is still about knowledge exchange. But different partners and different topics. Today it is more about sustainability and survival strategies for artists. I think sustainability is the arching topic which IETM is talking about today. You see more and more activities about capacity building, strengthening vulnerable partners and artists to survive in this transnational landscape.

Low: I am kind of curious because I always see Belgium as a right place at the right time, with the right content, … it is like these elements got in in the right constellation: whether it is the IETM, or policy makers responding, or these abandoned venues where artists make works… All these elements you talked about allow this to happen. We always say that we don’t quite have those things, but we have other things. So my question is, as a researcher, how do you begin to analyze some of these elements? And in the last two days, you have been hearing a lot about challenges and possible solutions, how would you begin to take some of these things to strategize or format in order to deal with the situation?

Janssens: As you say, it was a combination of elements. It is quite exceptional that they came together, so what can you learn from that? First thing is it is always easy to look back and try to understand what has happened. And then you see that somehow all functions in the ecosystem have been dealt with. But it was not strategic planning when it all started. So I think it is important to begin with really concrete things: to find solutions for specific issues. And to see what happens, to see what resonates and how things develop. Maybe you can also look back on what has happened in Flanders and Europe to see possibilities… but just do not copy it or try to do it all in the same time. Choose specific elements, prioritize, and work on that.