part 1: How did the visual arts scene come into being (till 2006)?

The general description below brings the motivations, the individuals, organizations and government agencies that give shape to the art scene in Flanders into perspective.

Part 1 provides a bird’s-eye view of the history of visual art in Flanders between World War II and 2006. Part 2 offers an overview of the field as it is today, including the organizations, artists and the art market, as well as noting the challenges it currently faces.

Introduction

By the term ‘contemporary visual art’, we refer to a diverse range of artistic practices and sub-disciplines, from painting and sculpting to installation art, graphic design and printmaking, video, film, performance, sound art, art created for public space and crossovers with different sectors and disciplines.

For a relatively small country such as Belgium, the visual arts here are extremely rich and of very high standard. For many decades, visual art in Belgium developed from the bottom up: from the conviction and enthusiasm of strong, individual players. Only in the late 1990s did a well-conceived, government-level strategy begin to take shape for the further development of contemporary visual art and its diverse participants.

In both Brussels and Flanders, the visual arts field is comprised primarily of small and mid-sized actors who operate in the periphery of London, Paris, Amsterdam or Düsseldorf, the home bases for powerful government-funded actors of international renown.

Brussels has in fact been enjoying a rigorous rise as a new hot spot for the visual arts. Growing foreign interest in what Brussels has to offer, as well as its context, is supported by a fruitful cross-pollination between affordable working spaces, residence possibilities, internationally oriented exhibition spaces, and galleries and collectors from both Belgium and abroad.

The city of Brussels had long lacked a museum of contemporary art of its own (see The Absent Museum, a statement exhibition at WIELS, 2017). That changed in 2017, with the arrival of KANAL-Centre Pompidou.

A Field in the Making (1950-2006)

We begin this overview after the end of World War II, although organizations and institutions that existed before the war continued to have a major impact and still play a vital role today.

The founding of the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels in 1928 was a landmark event. Today’s BOZAR, the Centre for Fine Arts was then well ahead of its time: it brought all art disciplines under one roof, had no collection of its own but was open to the art of the day and the future, with the aim of connecting Belgian art with the international art scene.

1950-1970 – Driven by Individuals

In the late 1950s and throughout the 1960s, a few highly motivated artists and art lovers organized exhibitions and lectures with artists from the international art scene, including Joseph Beuys, James Lee Byars and André Cadere. They established art galleries with networks with the art scenes in Amsterdam, Cologne and Düsseldorf.

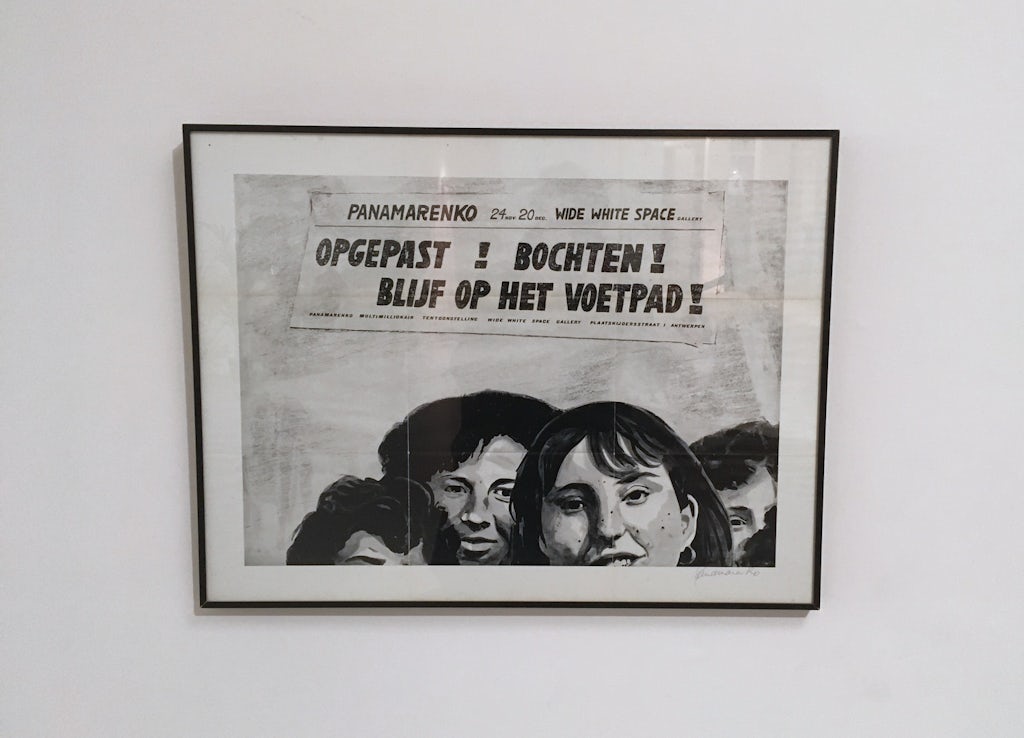

Artist Bernd Lohaus and art historian Anny De Decker opened Wide White Space Gallery (1966-1976) in Antwerp, focusing on avant-garde and contemporary art. In Aalst, art historian Roger D’Hondt established the New Reform Gallery, with, from 1970 to 1979, performance, concrete poetry, video, film, theatre, experimental music and conceptual art.

By Nieuwe haas – Eigen werk, CC BY-SA 4.0

In Brussels, in 1970, artist and critic Fernand Spillemaeckers founded Galerie MTL, a platform that presented more than 100 exhibitions whose primary participants were the protagonists of conceptual art.

In addition to the galleries, art magazines were published by art lovers and critics. They were an ideal format in which to make new developments in the visual arts known to the public, as well as helping create an active community of interested followers.

There was one major exception to the initiatives being individual or private. In 1950, the City of Antwerp founded the Middelheim Museum as a venue for exhibitions of outdoor sculpture. It was the first public institution for modern and contemporary art in Flanders.

As time passed, individual art lovers and collectors would continue to take the lead. In 1957, together with a group of art collectors and other like-minded spirits, lawyer Karel Geirlandt established the Gentse Vereniging voor het Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst (VmHK, The Ghent Society for the Museum of Contemporary Art), in part from dissatisfaction with the years of conservative policies of the Gentse Museum voor Schone Kunsten (Ghent Museum of Fine Arts). By 1975, the society had finally convinced the City of Ghent to establish the first museum of contemporary art in Flanders within the walls of the existing Museum of Fine Arts: what is today the S.M.A.K. (Municipal Museum of Contemporary Art). In 1999, under the directorship of Jan Hoet, the S.M.A.K. would finally have a building of its own.

In 1967, Jules Dhondt and Irma Dhaenens opened the Dhondt-Dhaenens Museum close to the village centre of Deurle aan de Leie. It continues to house its own collection of Flemish artists, as well as offering space for diverse cultural and artistic activities.

In 1976, the citizens of Hasselt founded the CIAP Platform for Contemporary Arts as a presentation space for contemporary art for a broad local and regional audience. The CIAP is a members association based on the German Kunstverein model. CIAP merges with FLACC in 2022 under a new name Jester.

1970-1980 – Provincial, City and Town Initiatives

In 1970, national restructuring of the Belgian state formed a first step towards Flemish cultural autonomy. From 1971 to 1980, the Nederlandse Cultuurgemeenschap (Dutch Cultural Community) was the predecessor to today’s Flemish Community. In Antwerp, they established the ICC (International Cultural Centre), the first government-funded institution in Flanders for the exhibition of contemporary art, directed initially by Ludo Bekkers, later by Flor Bex.

In the mid-1980s, that initiative resulted in the Museum of Contemporary Art, now known as the M HKA (Museum voor Hedendaagse Kunst Antwerp), again led by Flor Bex. Today, the M HKA is the largest museum of contemporary art in Flanders and operates according to a management agreement with the Flemish government.

At virtually the same time, in Oostend, the Province of West Flanders opened the Provincial Museum for Modern Art, or PMMK — today’s Mu.ZEE. Their collection policy is founded on Belgian art from 1830 to the present and the connections between modern and contemporary art.

In 1986, the Province of Antwerp opened the Museum of Photography (Fotomuseum) in an old warehouse on the Waalse Kaai, providing a home for a collection begun back in 1965.

The Flemish provinces also opened exhibition spaces for contemporary art. In 1996, in Hasselt, the Provincial Centre for Visual Arts, or PCBK, now Z33, opened its doors. BE-PART, the provincial platform for contemporary art in Waregem, opened in 2014.

In the 1970s, the predecessor to the Flemish Community began its own policy for the purchase of art, primarily as a means of supporting artists. From 1992, this social support policy shifted towards a collection policy, aimed at the purchase of high-standard, strong works of art that can provide a suitable image of Flemish art in an international context.

In the 1970s, Flanders moreover invested in establishing cultural centres, in part thanks to the regionalization of federal cultural policy. These centres were and are intended to help democratize culture through dissemination and active cultural participation and practice. De Warande in Turnhout (est. 1972) was one of the first of these to open its doors. In addition, these cultural centres set up lending facilities for contemporary works of art.

From there, in the early 1980s, the Kunst in Huis organization was established to collectively manage these local lending centres. Educational initiatives for children, young people and families also developed, occasionally also focused on art programmes in compulsory education. One example was Kunst maakt school (Art Makes School, est. 1988), an educational organization in Turnhout, which later became Kunst in Zicht (Art in Sight).

Consistent with its vision of dissemination and democratization, the Flemish government stimulated the integration of art in government buildings by way of a decree, dated 1986. It stipulates that for every new building that the government builds, or that is up to 30% subsidized by government, a certain percentage of the construction costs must be used for integrated works of art. In this way, art acquired a permanent presence in public space. More than ten years later, in 1999, an ‘Art Cell’ was added to the team of the first FlemishBouwmeester, or government architect, Bob (bOb) Van Reeth, which advised authorities in the integration of works of art and consequently improved the quality of the results. This Art Cell was later renamed the Platform Kunst in Opdracht (Platform for Public Art Commissions) and has been a part of the Department of Culture, Youth and Media, or CJM, since 2016.

1980-2000 – Initiatives within the Sector

As had been the case in the 1960s, since the 1980s, there has been a strong dynamic on the parts of artists and curators who have made contemporary art visible through exhibitions and artistic projects. To achieve this, they primarily rely on their own networks and incentives.

Where there are no public institutions for contemporary art, they make use of those cultural organizations that do exist, or they set up their own non-profit structures. Jan Hoet, for example, worked with the collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art housed in the Ghent Museum of Fine Arts, and in 1986, he took his influential Chambres d’Amis exhibition outside the confines of the museum and into the private homes of the citizens of Ghent.

Between 1986 and 1988, with the support of such curators as Bart Cassiman and later Dirk Snauwaert, director of exhibitions Jan Debbaut presented new generations of fine artists at the Centre for Fine Arts (BOZAR) in Brussels.

In 1985, Chris Dercon organized the Doch Doch exhibition during the Klapstuk dance festival in Leuven, and the following year the In de Maalstroom exhibition at the Centre for Fine Arts in Brussels. Due to the limited number of art institutions available to them in Flanders, talented curators have had difficulty finding locations and consequently move out of the country. Nonetheless, in the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s, a number of curators and artists founded new organizations, financed either through project grants or private sources. They include:

- Montevideo (1981-1984), founded by Annie Gentils and Stan Peers;

- Kanaal Foundation in Courtrai (1987-1998), by curator Catherine de Zegher;

- Roomade (1996-2006), by curator Barbara Vanderlinden;

- Croxhapox in Ghent (est. 1990), by a group of artists;

- Etablissement d’en Face, an artists’ initiative in Brussels (est. 1991), by artists Alec De Busschère, Delphine Bedel, Christophe Draeger and Patrick Everaert;

- Argos (est. 1989), the Brussels organization for the exhibition and distribution of video, by Koen Van Daele and Frie Depraetere;

- Kunsthalle Lophem in Loppem (est. 1992), by Roland Patteeuw;

- Interactive Media Art Lab iMAL in Brussels (est. 1999), by Yves Bernard;

- The NICC, with its associated exhibition space (est. 1998), by an association of artists; and

- Objectif Exhibitions in Antwerp (1999-2016), founded by curator Philippe Pirotte, artist Win Van den Abbeele and art historian Patrick van Rossem.

The 1980s and 1990s also saw the emergence of highly motivated individuals who were active in important galleries in Belgium, including Galerie Micheline Szwajcer in Antwerp, Albert Baronian in Brussels, Galerie Richard Foncke and Het Gewad in Ghent, and Bruges la Morte in Bruges.

Two specialized museums were founded in the late 1990s. The first to be built was the FeliXart Museum in Drogenbos, opening in 1996 and dedicated to updating and contextualizing the work of the painter, Felix De Boeck. In 2000, the Raveel Museum Association also completed the new Roger Raveel Museum in Machelen, with the support of the Flemish and municipal authorities.

Some historically orientatedart museums, such as the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels, and the Museums of Bruges, including the Groeninge Museum, also pursued policies of collecting contemporary visual art. They included contemporary works in their temporary exhibitions as well as in presentations of their collections.

Flemish Government Policy from 1990 to 2006

The Flemish Commission for Visual Arts, or VCBK, was established in 1982. As an advisory committee comprised of professionals from the visual arts sector, it provided support to the Minister of Culture in making decisions about purchasing works of art and granting awards to artists.

Only a decade later, in 1992, under director Jef Cornelis, would the VCBK establish a policy of subsidies and grants to support visual art and artists, a policy that would be expanded and refined in the late 1990s, becoming a ‘pre-decretal regulation for the visual arts sector’. This consisted of annual and project grants for organizations and an overall policy for government-funded purchase of art, as well as grants for artists in the form of start-up and working grants, project grants, international project grants, and partial grants for travel and lodging in artist residencies in other countries. An additional regulation was later added to help support galleries that promote Flemish artists at important international art fairs outside Belgium.

The Performing Arts Decree had already been approved in the early 1990s. Following the model of the Netherlands, groups and institutions in the performing arts could submit applications for support for structural plans or projects. Once accepted on the basis of quality standards, they could be approved by a committee of experts to receive annual subsidies on a four-year basis or project grants for a single year of operation.

Visual arts organizations had to wait until 2006 for the implementation of the Arts Decree, an umbrella framework for subsidies and grants for the entire arts sector, before they too could qualify for multi-year subsidies. This delay in support policy explains the gap between the performing arts and the visual arts. While the performing arts in Flanders had been able to build up an important field of makers and organizations, the visual arts were only able to do so beginning in 2006, at a point when the steady increase of subsidies and grants in the arts was stagnating due to economic cutbacks, and would, from 2010, actually be reversed.

Despite the catch-up manoeuvres and promises to give the visual arts equal treatment in 2006, more new economic cutbacks would mean that the gap between the performing and the visual arts in Flanders would not only not be eliminated, but would grow even larger. From year to year, project grants and subsidies for visual artists continued to oscillate in both numbers and the amounts awarded. Only in 2013 would the level achieved prior to 2010 again be reached. In 2019, only 25 organizations, of a total of 207 which make use of operational subsidies through the Arts Decree, exclusively concern the visual arts. Together, these kunsthallen, production platforms, working spaces and residencies represent slightly less than 7% of all working subsidies and grants in the arts. In addition to these visual arts organizations, there are of course multidisciplinary arts centres, periodical publications and presentation platforms that do focus some of their attention on the visual arts.

A variety of initiatives have been undertaken to strengthen the overall position of the visual arts. In 1998, artists established the NICC, or New International Cultural Centre, in order to support and defend their interests. Their specific motivation at the time was the closure of the ICC, the International Cultural Centre. The NICC focuses on advancing the socio-economic position of artists, operates as a partner in discussions and negotiations on behalf of the position of artists in government cultural policy, develops policy for artists’ working spaces and redresses the lack of possibilities for presenting the visual arts by establishing project centres in the different provinces.

In anticipation of the Arts Decree, in 2002, the Flemish Community established a support point for the visual arts that focused on the professionalization and internationalization of the sector, as well as overall cohesion in the field. Called the IBK (Initiatief Beeldende Kunst, or Initiative for Visual Art), it would fuse with the IAK, the Initiative for Audiovisual Arts, in 2007 and operate with them jointly as the Flanders Arts Institute, or Kunstenpunt, for music, visual and performing arts.

In 2006, visual arts organizations set up the VOBK, the United Visual Arts Organizations, in order to defend the interests of the visual arts organizations within the context of the new decree, and they would later fuse with other employer organizations in what is known as the oKo, Overleg Kunstorganisaties (Industry Federation of the Arts).

Contemporary Art Heritage Flanders (CAHF) is a knowledge platform concerned with the collections of four museums of contemporary art in Flanders, namely S.M.A.K., Mu.ZEE, Middelheim Museum and M Leuven.

Today, many of the museums mentioned above, including M HKA, Middelheim Museum, Museum Dhondt-Dhaenens, Mu.ZEE and S.M.A.K. receive operational subsidies through the Heritage Decree. As a result of internal government reorganization in Flanders, as of 2014, provincial cultural organizations have come under the auspices of either a municipal government or the Flemish Community.

Conclusion

Contemporary visual arts in Flanders evolved from the bottom up, thanks to the incentives and commitment of highly motivated individuals, including artists, curators, collectors and gallery owners, as well as through various urban, provincial and Flemish Community policies and visions.

Due to a lack of structural policy frameworks, exciting initiatives were not always able to continue their development. Important knowledge and skills have been lost, while fragmentation means greater inclination towards competition, rather than collective enterprise.

In the last 15 years, a reversal has taken place, marking a stimulating ecosystem of private, public and non-profit actors who now work more collaboratively in order to build a visual arts landscape for tomorrow, with a strong bond to society as a whole. Part 2 provides an overview of the current field of organizations, artists and the art market.

(Translated by Mari Shields)