Hop until you drop? The (difficult) alliance between urban and contemporary dance

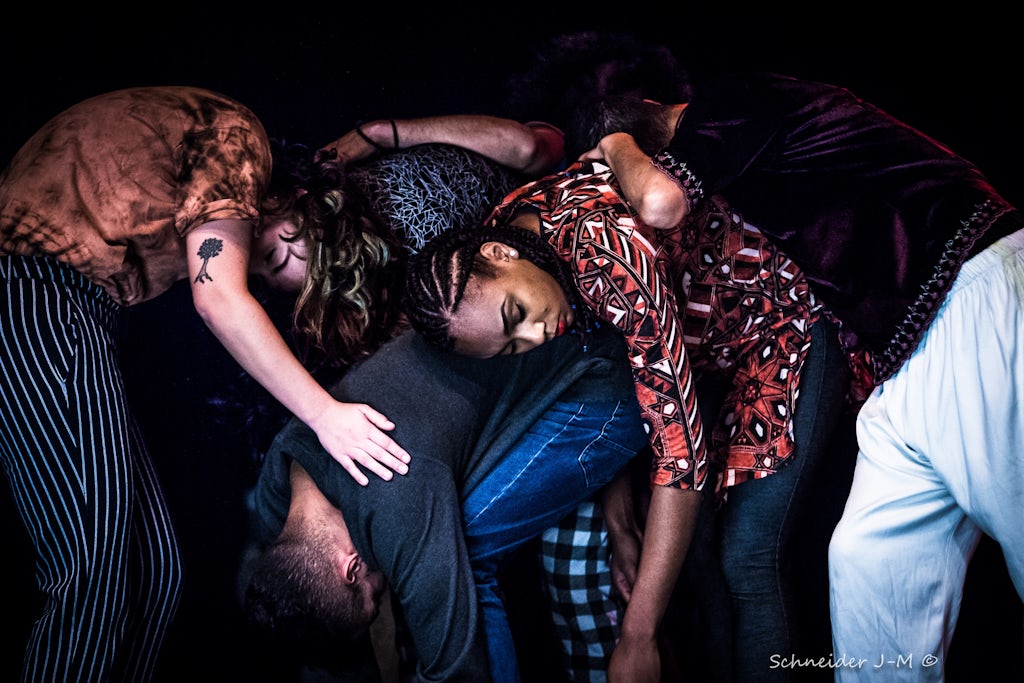

Rhythm Naturals (c) Jean-Marc Schneider

Urban dance has grown from a streetwise subculture into a form that is ubiquitous on television, in the music industry and in the world of contemporary dance. The ‘genre’ therefore has a nice future ahead of it. Or does it? For it appears that much remains to be done in Flanders in order to offer the urban culture the structural support and artistic recognition that it potentially deserves. Three pioneers talk about the adversity and prejudice they wrestle with, despite the current hype. ‘The chances we’re given can’t be fake.’

Urban dance (1) is here to stay. Not only are makers keenly experimenting with it in shows for young audiences – just think of the recent fABULEUS shows Rats and Popcorn – but even in the bastion of contemporary dance, styles such as breaking, krumping, popping, locking, hip-hop, dancehall and voguing are increasingly catching on. Choreographers such as Ula Sickle, Helder Seabra, Randi De Vlieghe, Bruno Beltrao, Wim Vandekeybus, Cecilia Bengolea and François Chaignaud work with dancers from the world of street dance or draw their inspiration from urban movement material that they confront with choreographic tools and dramaturgic principles from contemporary dance.

This interest is certainly not new – Alain Platel’s Iets op Bach (1998), for instance, is an important reference show – but the scale and symbolic reach are. Urban arts feature more prominently in the programmes of an Open Talents House such as Zinnema or of Gemeenschapscentrum Pianofabriek, but also, since this season, of the Royal Flemish Theatre KVS. And for several years now STUK has been engaged in a partnership with Straatrijk, a sociocultural organisation that sees urban dance as a fully fledged art form.

Urban dance therefore seems to be ubiquitous. But is it? If you take the Flemish subsidies as an indicator, a very different picture emerges. Since the termination of Hush Hush Hush in 2006, not a single Flemish dance company has emerged that makes shows based on urban dance and that is subsidised under the Arts Decree. Let’s Go Urban, the Antwerp-based organisation centred around Sihame El Kaouakibi, did indeed submit an application during the last structural round, but it was turned down.

Policymakers continue to see hip-hop as a way of keeping delinquent youths off the street, as a glorified form of fringe animation.

Hush Hush Hush was founded by the Moroccan-born electrician and streetworker Abdelazziz Sarrokh in 1996, after he was discovered by Alain Platel. What began as a sociocultural project in the lap of the Berchem cultural centre grew into a structured dance company that combined urban dance, contemporary dance and theatre. After ten successful years and many European tours, the company’s subsidies were discontinued. We have been waiting for a successor ever since. In this respect Belgium is significantly lagging behind France, where for the past 30 years already the authorities have been betting heavily on urban dance and where companies managed by a hip-hopper or b-boy are well established and tour widely: just think of Kader Attou’s Cie Accrorap, Mourad Merzouki’s Cie Käfig and Brahim Bouchelaghem’s Cie Zahrbat.

Twenty years ago already, Dirk Verstockt and Bart Eeckhout wrote in Etcetera about what hip-hop had to offer contemporary dance. (2) Two decades later, urban dance in Flanders appears to be fully legitimised within the frame of contemporary dance, where it is, prudently, a structural part of the movement vocabulary. But as an autonomous art form, urban dance remains condemned to the commercial circuit, the leisure sector or the underground. How can we account for that gap in terms of symbolic capital and institutional recognition within the arts sector?

On the one hand, it is problematic to use the history of hip-hop – which emerged in the 1970s in the poor, mainly black ghettos of America – as an argument for that ambiguous position, as if urban dance by definition does not permit institutionalisation. On the other hand, it is also too easy to interpret hip-hop only through the lens of glitter and glamour, as the music industry and the world of advertising often do. What steps need to be taken to emancipate urban dance artistically in Flanders? How can the exchange between the ‘high’ and ‘low’ dance cultures in Flanders become more of a two-way process?

I put these questions to a number of people who know the urban dance scene inside out. The Molenbeek-born Yassin Mrabtifi learned to hip-hop in Gallery Ravenstein in Brussels, is a member of Wim Vandekeybus’s company Ultima Vez and is currently working on his debut, From Molenbeek with Love, at the KVS. Samir Bakhat is the artistic director of the Antwerp-based street and urban company Rhythm Naturals. And choreographer Abdelazziz Sarrokh has been working, since the dissolution of ‘his’ Hush Hush Hush, at Victoria Deluxe in Ghent, where he accompanies dance projects with youths. (3)

A problem of perception

Samir Bakhat admits that at first, he did not want to come. We have only just met in a café in Antwerp and the issue of the conversation is immediately highlighted. ‘I’ve told my story so often already. I’ve written policy recommendations and arranged debates at the Urban Dance and Sports Festival that I organise, but nothing changes structurally.’ So although urban dance may have ‘made it’ officially in the contemporary dance world, the scene itself, according to Bakhat, still struggles with a persistent problem of perception. ‘Policymakers continue to see hip-hop as a way of keeping delinquent youths off the street, as a glorified form of fringe animation, but we moved on from that a long time ago. It is not only a problem of the arts sector. The immigrant community remains chronically underrepresented in every section of society.’

Bakhat’s critique of inequality in society and the arts world, and the resulting limited growth possibilities for urban dancers – who mostly still come from communities with other ethnic-cultural roots, although the dance form is also becoming more popular among the autochthonous population thanks to TV programmes such as So You Think You Can Dance – will colour the rest of the conversation.

Bakhat founded Rhythm Naturals 12 years ago. The company creates performances and TV shows, organises an annual festival devoted to urban arts, coaches youths, and is artist in residence at the Deurne cultural centre. The collective can count on subsidies from the city of Antwerp and from the Flemish Community (under experimental youth work), but that is all at present. When you consider that after Hush Hush Hush no similar company has emerged or – such as Let’s Go Urban and the non-profit organisation Straatrijk – has applied for subsidies under the Arts Decree, you can ask yourself whether urban dancers are in fact interested in taking part in the professional field of performing arts.

Without a moment’s hesitation, Bakhat punctures that reserve. ‘Of course it is my dream to be recognised under the Arts Decree and to work as a fully fledged company, but we are not starting out from an equal position. Because of a lack of means, our non-profit organisation has no permanent employee. I am responsible for the artistic direction, but also for promotion, communication and casting. Try writing a subsidy application on top of that. We don’t have enough budget to hire someone external. Dēmos, the non-profit knowledge centre for participation and democracy, does what it can, but of course they can’t take care of everything.’

It is a remark that one often hears since the new Arts Decree has been in force. The administrative burden has increased drastically. For smaller organisations without an extensive entourage, it constitutes a serious extra load to their operations – all the more so when you come from a discipline that still has to prove itself in the eyes of a commission and the authorities. Intensive accompaniment therefore seems necessary, not only to make the step from urban dance to the official dance circuit, but also conversely: when subsidised houses draw in such artists.

During the latest subsidies round, Let’s Go Urban was twice declared ‘completely unsatisfactory’. Whoever has seen some of the company’s shows can well imagine that reserve about the artistic quality, although perhaps that is not surprising because the organisation presented itself in recent years as an Academy for young talent and under the Arts Decree wanted to raise means to develop a professional Dance Company. The city of Antwerp recently put an old reception hall at the disposal of El Kaouakibi for her activities, for which the youth service set aside a million euro. DeSingel too, drawing on the ‘participation’ function that it must fulfil as ‘Major Institution of the Flemish Community’, will support the work of Let’s Go Urban over the next five years. However, what sounds like a success story has for years already been the fruit of a one-person business. It does not take away that the driving force El Kaouakibi has an extensive network as a social entrepreneur and knows how to position her company in the market.

Rhythm Naturals is in a very different position. It performs its shows mainly at its own events (e.g. the Urban Sports and Dance Festival) and does not produce winners of So You Think You Can Dance. Branding is therefore a lot more difficult. ‘I refuse to broadcast a story in the media at the expense of the young, as though I were the pope in Rome who is trying to find a solution for unemployment and radicalisation. Again, this is not our purpose’, says Bakhat.

‘If you want to launch something and put hip-hop on the map in the arts circuit, you have to give people the space to develop and gradually to professionalise’, Abdelazziz Sarrokh adds. ‘Hush Hush Hush received an incentive subsidy in the 1990s. We were the first to bring in urban dance and a new audience. That is something the subsidiser simply couldn’t ignore. However, the chance we were given was a fake chance. We were evaluated with the same standards as those used for Rosas, Ultima Vez and les ballets C de la B. We had to create shows, sell ourselves and in the meantime learn to be self-supporting. As a young company we were simply trampled underfoot. We had neither the know-how nor the support to conquer a space of our own.’

Artistic emancipation

The unequal power relations that Bakhat and Sarrokh experience overshadow to a certain extent also the conversation about the artistic potential of urban dance. Both choreographers see many possibilities and are exploring cross-pollination with other disciplines (contemporary dance, circus, slam poetry) or ask a choreographer with roots in classical ballet, such as Michael Lazic, to coach dancers. But without either means or recognition, every artistic development fails at a certain moment. What’s more, the synergy with the commercial circuit – in our country, hip-hop events are often sponsored by Levi’s and Red Bull – is not always good for artistic credibility, even though Yassin Mrabtifi admits that it is often the only way to keep Belgian hip-hop alive.

‘Rhythm Naturals is forced to linger in the atmosphere of the socio-artistic’, says Sarrokh. ‘You can’t make a complete, evening-long show if you can’t pay professional dancers or a dramaturge and do artistic research thoroughly. We do try to recruit people who already have a certain experience, but that remains very much project-bound. Logically, the young prefer to take part in battles, because that allows them to earn something. Furthermore, there are no perspectives for them, let alone concrete work opportunities in the arts. Television, Cirque du Soleil or teaching then become the only options. As a company, you can’t build up lasting expertise in this way.’ Mrabtifi confirms: ‘In Brussels, for instance, hip-hop is subject to a constant movement of appearing and disappearing. When there are terrorist attacks, then we get more attention, so to speak. We help create an impression of sociocultural diversity and inclusion, but then it dies out again.’

That makes the status of hip-hop very precarious. Today the artistic legitimacy for urban dances comes mainly from the contemporary field, but it is possible that that interest will die down again in the coming years. Who will then still defend these dances, if the hip-hop scene has still not put itself structurally on the map?

Nevertheless, the key question remains: does Flemish urban dance have the strength to emancipate itself as a fully fledged art practice from the sport, leisure and entertainment circuit? Can it move beyond – let’s lump all the clichés together for a moment – virtuoso tricks, demonstrations of testosterone, commercial spectacle, its primary socialising and subjectifying function (4) and facile references to street culture?

In fact we need to turn the question around: why could it not? There are enough examples to be found abroad. Contemporary circus – also a discipline in which, from a historical perspective, technicity prevailed over an artistic message – is today undergoing a similar process of emancipation. Within contemporary dance too you see the potential. Choreographers such as Ula Sickle, François Chaignaud and Cecilia Bengolea demand recognition with their performances for urban dances as artistic practice, as a diverse collection of dance forms with their own eloquence, social reach, complex movement register and ditto construction principles.

In most cases, for these choreographers it is not only a matter of the revaluation of the vocabulary of contemporary dance, but also a more active synergy with the public, another presence and the integration of new representations of urbanity and diversity – consider, for instance, the work of Haider Al Timimi, who refreshingly interweaves breakdance and contemporary dance, Arabic folk songs and street vernacular in his work. Rather than just carrying out movement research, Al Timimi, Bengolea, Chaignaud and Sickle are therefore advancing urban-dance culture as a theme in itself.

Earlier I wrote about cross-pollination between contemporary dance, popular culture and a ‘nomadic’ concept of identity. (5) Urban dances are a physical witness of the process of cultural exchange, characteristic of a globalised society that was set on cruising mode by digital media and the Internet. Whether they emerged in the street or in a social and rather impromptu context, urban dances are constantly in evolution. They are contaminated by local traditions and global hypes, are by definition ‘diasporic’ and ‘glocal’, and are a symbol of our hybrid cultural experience in which roots and routes (6) increasingly overlap. Perhaps urban dances are in that sense more contemporary than what we traditionally understand under that term, which brings to mind the claim of sociologist and dance theorist Rudi Laermans: contemporary dance is mainly a discursive and performative category ‘which again and again is used from the premise that such a thing exists’ and which is socially validated by a certain milieu. (7)

Does Flemish urban dance have the strength to emancipate itself as a fully fledged art practice from the sport, leisure and entertainment circuit?

A single family

However, Mrabtifi, Sarrokh and Bakhat mainly feel that they are not part of that milieu and the corresponding artistic criteria. The success of contemporary dance in Flanders, in the wake of the Flemish Wave and the foundation of P.A.R.T.S. (which turns out the majority of choreographers operating in Belgium), seems to have partially hindered the development of urban dance. ‘The dance sector in Belgium sometimes seems to be run by a single family’, says Sarrokh. ‘They followed the same training and move around in each other’s network. Critics, policymakers and committee members mainly wield the codes of contemporary dance. “Then sit on the committee”, they say. That’s something I refuse to do. If you remain the only outsider among all white faces, you just become an alibi figure that has to defend his rank and file.’

That is also something that Mrabtifi experiences. ‘Contemporary dance shows cannot always surprise me. Repetition, flying low, dance theatre, groundwork: these are codes that recur frequently in Belgian dance. In hip-hop there is, at least in my opinion, a bit more room to experiment with a new movement language. By constantly improvising, you become highly alert: as soon as I get bored, I look for something new. That’s in the DNA of the dance form. At the same time, contact with contemporary dancers from Ultima Vez has made me aware of the power of simple movements.’

Bakhat goes further. ‘The shows available in the art circuit aren’t diverse enough. Much contemporary dance remains abstract for the young we work with, even boring. Contemporary dance uses complex formulas. There is nothing wrong with that, but for a large part of the audience it doesn’t work. What’s more, many urban dancers have other roots and a different religious conviction. They can’t always identify with the extreme, shocking method or the sexual intensity with which contemporary dance deals with the body. Self-worth and pride are very important for these dancers’, says Bakhat.

For whoever is up on contemporary dance, this sounds like an outright caricature. But neither do we ourselves escape it. Real knowledge about each other’s work still seems to be influenced mainly by preconceptions. ‘Whoever only watches So You Think You Can Dance imagines that urban dance is just a spectacle’, says Sarrokh. ‘But that’s not what it’s about. When we watch hip-hop, we see the gentleness and complexity of a headspin, the emotional overtone also. You miss that if you don’t have those codes.’

Horizontal exchange

Are there then no objective criteria by which to measure the professional quality of artistic work? Whoever watches one of the rare shows that comes from the Flemish milieu of urban dance notices that the dramaturgic perspective, the compositional-analytical skills and the deepening in terms of substance often remain superficial. These are precisely aspects that dancers learn to develop in a training. Is schooling crucial then after all to be able to make it in a heavily professionalised, underfinanced and competitive arts sector? By definition, urban dance rests on autodidacts, and that is also its strength, says Mrabtifi. ‘Hip-hop’s natural stage is the cypher, where people meet as equals. (8) It’s a horizontal learning process. Someone shows something, the other reacts to it. If you find something interesting, you pick it up and make it your own. There is no master, no one defines what hip-hop is. That is why the dance form can pick up so many influences from different cultures and you can get rid of so much personality in it.’

It is good that hip-hop is being picked up by the contemporary field, but it is problematic when the dance(rs) is (are) simply being used as a hype and then turned out into the street.

Can a form of urban-dance training exist that does justice to those horizontal principles and the dancer’s sovereignty, and that takes into account the fact that many of these dancers have already developed a practice over many years in the street, in clubs or in workshops? Educational reforms are slow-moving naturally and the question is whether such a form of training will be able to erase the threshold that people with other ethnic-cultural roots currently experience strongly in the arts education. In the meantime it appears to be opportune to invest already in sufficient guidance and in reinforcing the network of urban dancers within the cultural field. Platforms after the model of Transfo Collect or GEN2020 can also be a solution.

Continuity

It is not only through training that both worlds can grow towards one another. The circuits can also be better attuned to one another, Mrabtifi believes. ‘The contemporary dance scene and urban dance are the most important traditions in Belgium. Everyone has an idea of what is happening on the other side. In the hip-hop circuit, for instance, there is an experimental category for dancers that belong nowhere else – that is where I took my own first steps. The movement research that you see there looks a lot like how contemporary dance deals with the body. In categories such as popping and breakdance, the rules are a lot stricter: a DJ sets the music and you can’t, say, do a “robot” if you’re spinning on the ground.’

‘In the experimental discipline you can even propose your own dance language that draws on a range of traditions. That is why the move to the contemporary scene was not so big for me. Dancers who come from this category certainly have the power to develop into strong choreographers who can move beyond the attitude and stunts, the big clichés of hip-hop. We need meeting places where dancers from both spheres of influence can engage in dialogue with one another. In France there are lots of these types of events, where experimental and contemporary dancers work together.’

DansBAaR, an initiative of the Leuven-based non-profit organisation Straatrijk, is already seeking out that cross-pollination. Dance trios consisting of dancers with different dance styles face off in battles. Sarrokh goes further. ‘It is good that hip-hop is being picked up by the contemporary field, but it is problematic when the dance(rs) is (are) simply being used as a hype and then turned out into the street. We have to bet on continuity and on the development of choreographers who themselves come from the scene. This is not only a tale of too few subsidies.’

Appropriation or exchange?

In her book Hallo witte mensen (2017; Hello, white people), Dutch writer Anousha Nzume discusses the concept of ‘cultural appropriation’. By this she refers to the ‘whitening of traditions from other cultures (…) without awareness of the (political) history’ (9) whereby they attain a status. It is generally about customs that used to be the subject of negative stereotypes. Nzume’s discourse is far from unproblematic: a terrible danger lurks in the essentialising of cultural expressions. Culture is par excellence something that migrates, and urban dance is the best example thereof, as Mrabtifi described it: ‘It’s a pass around the world.’ Let alone that we must politicise each cultural utterance. That either maintains polarisation, or is a safe conduct to ignore artistic criteria. What Nzume’s text does invite us to do is to become aware of the institutional inequality and the white privilege (in this case: the dogma of contemporary dance) that defines the process of cultural experience and expression in our art world to a certain extent.

We are trying to show content from Vimeo.

Kunsten.be only uses minimal cookies. To view content by a third party website, this site can place additional cookies. By continuing to browse you are agreeing to the use of those third party cookies.

Read more about our privacy policy?

These are critical aspects that choreographers such as Ula Sickle, François Chaignaud and Cecilia Bengolea really do include in their shows. For instance, in Kinshasa Electric (2014), a collaboration with three Congolese dancers, Sickle always has a local guest dance along at the place where the show is touring. Despite their low degree of mobility, she also tries to engage in longer collaborations with the group and to develop their network. In Altered Natives Say Yes To Another Excess – Twerk (2014), Bengolea and Chaignaud place street dancing in a critical genealogy with the work of a recognised dance pioneer like Martha Graham and they go back to the subversive roots of the twerk: not Miley Cyrus, but Jamaican dance-hall queens who were fighting against the coloniser’s patriarchal gender ideology. In Tour du monde des danses urbaines en dix villes (2016; Tour of the world of urban dances in ten cities), they give a danced reading-conference in which they shed light on the emergence, social context and evolution of urban dances.

We cannot expect much more than these critical positions from the artists themselves. But we can from policymakers, programmers, cultural centres and critics. To really achieve cultural exchange, the power relations have to be reworked, says Nzume. In that regard the Flemish urban scene still has a whole battle to fight that will be decisive for its artistic emancipation.

Foot Notes

- As a collective name used for all the dance styles that emerged in the street or in an informal context, this term is not universally accepted. KVS city dramaturge Gerardo Salinas prefers to talk about ‘art of the new urbanity’, by which he means both the professionalised arts sector and ‘the less documented practices that have developed organically out of urban contexts’. He finds this term more inclusive than ‘urban dance’, which he sees as too restrictive as a label and which also supposes certain judgements of quality. A concept such as ‘art of the new urbanity’ emphasises the city as the shared territory of different artistic practices and as such ensures more dialogue between the different artistic visions. See: Gerardo Salinas, ‘Migratie, kunst en stad’, available for consultation on: planvoora.be. (in Dutch only)

- Dirk Verstockt, ‘Move your ass and your mind will follow’, Etcetera 15. Bart Eeckhout, ‘Hiphop na de hype. Danse urbaine’, Etcetera 16.

- This report only offers three personal perspectives on the issue and therefore does not intend to present an objective state of affairs of the status of urban dance in Flanders. For that, more extensive research is needed. Ten years ago already, Evi Bovijn, who was doing a master’s degree in cultural sciences, made a praiseworthy attempt with her thesis, Urban dance in Vlaanderen: From streets to stage? Kwalitatief onderzoek naar de positie van urban dance(rs) in de podiumkunsten. (2007-2008). Available for consultation on: amateurkunsten.be. (in Dutch only)

- Pascal Gielen, ‘Cultuur als zingever. Over kunst, cultuur en creativiteit’, Courant 109 (Art and politics).

- ‘Ass talk en clubbing vibes: Nomadische identiteiten in de hedendaagse dans’, Etcetera 139.

- John Storey, Inventing Popular Culture: From Folklore to Globalization, Blackwell Publishing, 2003.

- Rudi Laermans, ‘Hedendaagse dans, wat is dat? Petite leçon sociologique’, Etcetera 91.

- ‘Anything cyclical. If [you’re] freestyling, you rap in a cypher (one after the other). Interrupting another man will break that cypher (unless he’s next in line and the dude behind him is falling off) (…)’ urbandictionary.com

- Anousha Nzume, ‘Waarom je Kendrick Lamar serieus moet nemen en niet zomaar kunt twerken op Beyoncé’, De Correspondent 19/04/2017.