Women of note: female composers in Flanders

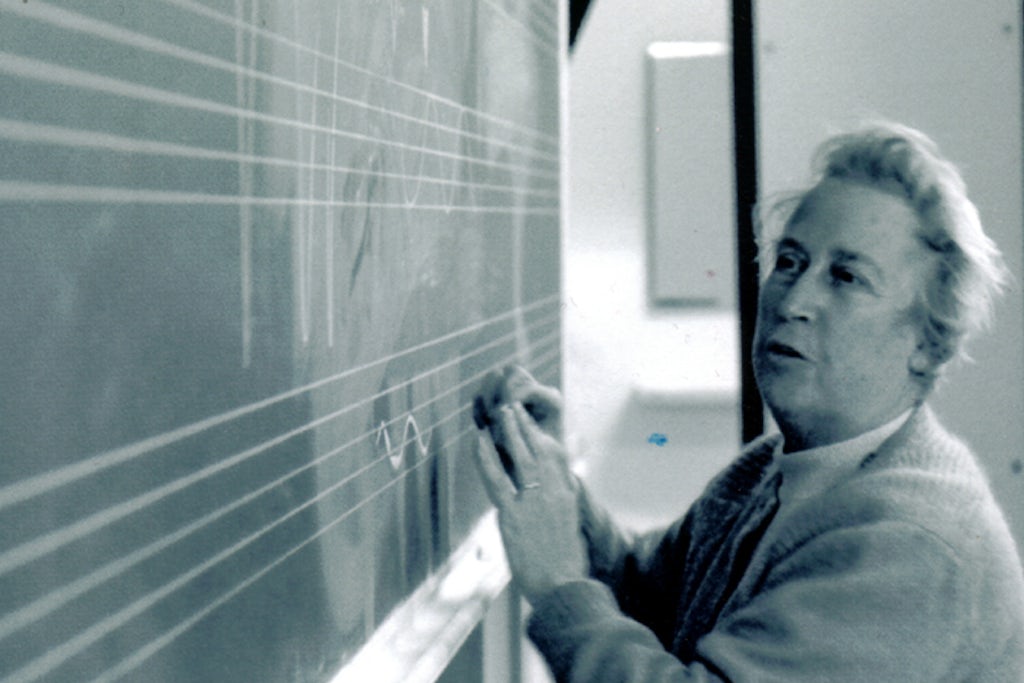

Jacqueline Fontyn

The struggle for gender equality in classical music is not over yet, and not in Flanders either. Anyone who flicks through books about Flemish music history, whether they are old or new, will hardly find any women in them. A recent example is the book “In gesprek met componisten uit Vlaanderen” (In Conversation with Composers from Flanders) by Simon de Rijcke. The imbalance presented once again in this new book prompted us to write this text.

The logical question that follows is: have there really been so few female composers working in Flanders? Anyone who investigates will soon find out that there were indeed fewer women than men in history who composed music. The reason for this is not a lack of talent among women. Listening to their work today proves that, and audiences and musicians in their own time were also enthusiastic. The limited presence of women in music history has everything to do with the place women were permitted to occupy in society until recently: a position subordinate to men, in which they were responsible for housekeeping and childcare.

Access to music under certain conditions

Women only received official access to musical education in the nineteenth century. Before then, only girls from specific backgrounds, such as nuns and aristocrats, could gain access to education. The idea that it was indecent for a woman to make music was introduced by the Church in the Middle Ages. It is not the aim of this text to investigate that issue, but Simonne Claeys’ Het Tweede Thema (‘The Second Theme’) is a good starting point for anyone wishing to find out more. This attitude continued to resonate in society for a long time, impeding the professionalisation of female musicians.

One of the first known Flemish composers is Leonora Duarte (1610-1678). She came from a rich family of art lovers and had private lessons in the violin, harpsichord and lute as well as composition. A manuscript containing seven sinfonias for a consort of five viols by Leonora has survived. She is the only seventeenth-century woman who wrote viol music that is known today. Furthermore, her sinfonias are unique in that they were not commissioned by the Church or court. They belonged within domestic musical life: the Duartes’ musical salons. The first full recording of her work appeared in 2018, performed by Transports Publics on commission from Museum Vleeshuis.

The democratisation of musical education began in the early nineteenth century. Several conservatories were founded in Flanders, in Brussels (1832), Ghent (1835), Antwerp (1844) and Lemmensinstituut in Mechelen (1879). In 1968, Lemmensinstituut moved to Leuven. It is unclear whether girls were admitted to theoretical classes as well as practical ones from the outset, or whether they had to wait until the end of the nineteenth century.

Although nineteenth-century women gradually gained more access to the professional music scene, they continued to experience difficulty building a career and making music in public. Especially after marriage, women often withdrew from the concert scene. Wealthy ladies were able to create a place in musical salons to express their musical talents as performers or composers nevertheless. Although the salons thus gave them a degree of freedom, they also had a limiting effect. Women mainly composed chamber music because that was what could be performed in salons. The fact that these were high-quality works was irrelevant in a society where composers only gained status after writing a symphony or opera. Although these women matched their male counterparts in terms of knowledge and ability, these social restrictions prevented them from developing their career in the same way.

Further professionalisation of women as musicians

This finally began to change around the turn of the century. The idea that women could not be composers started to wane in the major Flemish cities. Nonetheless, it is striking that the female composers all had similar profiles. They were wealthy and highly educated. As a rule, they had no children or were able to entrust childcare to other people. That gave them the freedom and opportunity to develop their musical talent.

Een van de weinige vrouwelijke componisten die actief was rond de eeuwwisseling, was Cecilia Callebert (1884-1978). Ze werd geboren in een artistieke familie en kreeg van jongs af aan pianoles van haar familieleden. Na haar piano-opleiding in een Antwerpse privéschool werd ze toegelaten aan het One of the few female composers active around the turn of the century was Cecilia Callebert (1884-1978). She was born into an artistic family and received piano lessons from relatives from a young age. After piano training at a private school in Antwerp, she was admitted to the Royal Conservatory of Brussels. Callebert was unable to develop a career as a concert pianist due to health issues, but she was highly active as a teacher and composer. Around two hundred of Cecilia’s works have survived. Her oeuvre consists mainly of vocal religious pieces that can be linked to her education and the contact she had with the Franciscan nuns or Grey Sisters. She distanced herself from the new musical currents of the twentieth century, writing in a more conservative style.

Palmyre Buyst (1875-1957) won various first prizes at the Royal Conservatory of Ghent, including prizes for practical harmony and piano. Her performances were highly acclaimed. As a composer, she wrote pieces for large and small ensembles, ranging from chamber music to orchestral works and even a few cantatas.

Her daughter Jeanne (Jane) Vignery (1913-1974) received music lessons from her mother and grandfather at an early age. She studied the violin at the Royal Conservatory of Ghent and took harmony lessons from teachers including Nadia Boulanger. An incurable muscle fatigue disease forced her to give up her career as a violinist, and she decided to devote herself entirely to composing and teaching. Her sonata for horn and piano (opus 7) is a much-loved repertoire piece. It was probably written in 1942 and combines a traditional form with an impressionistic style.

Besides increasing their professionalism, studies at the conservatory also gave women the opportunity to expand their musical network. They got to know other composers and performed each other’s work. As teachers, they had the opportunity to draw attention to their own work and that of their colleagues. In short, it became considerably easier for them to come into contact with performers, impresarios and concert organisers who could publish their work and make it known to a wider audience.

Unknown is unloved

Irène Fuerison (1875-1931) did not study at the conservatory, which made it harder for her to get her career off the ground. At the age of nineteen, she married the prosperous lawyer Joseph Fuerison. It seems that she mainly made music in a domestic setting during the early years of her marriage. Her first compositions probably date from the period 1900-1915, the period in which she also lost her sight. Her work was received positively by audiences and professional musicians. Irène also wanted to publish her work. To do so she needed both her husband’s support and connections, and enough money.

Although Irène was successful abroad as well as in Belgium, she continued to have difficulty getting her work published. She ultimately succeeded in getting a few works into print by financing the project herself. The importance of publishing scores at that time cannot be overemphasised. Besides concert halls, the salons and drawing rooms mentioned above were the main place where people could experience music. Both listening to music and performing it oneself were important aspects of musical life, certainly until the radio and other sound media emerged. Composers who were not published were not performed, and so they did not achieve the renown they needed to get their work published: a vicious circle.

This is why much of Irène’s work, along with that of many other women, has been consigned to oblivion. A lack of network, financing and renown meant that their work was not published. If you wanted to perform a piece, you had to ask the composer’s permission to see the manuscript. Then you might be able to copy it out by hand, which was a very labour-intensive process. No publication meant that there were hardly any copies of compositions, so they were more easily lost. This vicious circle still makes itself felt today. Only a fraction of the work by female composers has been preserved, and many of those scores have been left to gather dust in archives. The composers are still unknown to audiences because there are no concerts or recordings of their work, and these concerts and recordings never happen because there is supposedly no interest. This is how a repertoire has developed that hardly includes any compositions by women.

Major institutions in Flanders

In Flanders, Yvonne Van den Berghe (1908-2004) was a key figure in the distribution of female composers’ repertoire. Very little is known about her, except that she was a pianist who also taught. Among other things, she performed work by her piano pupil, the composer Nini Bulterys (1929-1989), with the BRT radio orchestra. Nini won various prizes, including the Prix de Rome, and came second in the Queen Elisabeth Competition for composition. In turn, she taught fugue and counterpoint to various Flemish composers who are also included in the In gesprek met… (‘In Conversation with…’) book. Nini was an assistant programmer at the BRT. That was a unique position for a woman at the time.

The Belgian public broadcasting service employed many male composers in that period, who worked there as programmers, producers or the conductor of the radio orchestra. Professional orchestras, including the radio orchestra, brought the work of Flemish composers to a wider audience and thus ensured their fame. Besides the N.I.R. radio orchestra (1935), now called the Brussels Philharmonic, Flanders also had a National Orchestra of Belgium (1931), Flanders Philharmonic (1955, now Antwerp Symphony Orchestra) and Flanders Symphony Orchestra (1960). As well as orchestras, famous soloists ensured that the work of Flemish composers was played. For example, Yvonne Van den Berghe regularly performed works by Denise Tolkowsky and Jacqueline Fontyn, two women who were each linked in their own way to one of the most important commissioning bodies of new work by Belgian composers, the Queen Elisabeth Competition.

The talents of the pianist and composer Denise Tolkowsky (1918-1991) revealed themselves when she was still very young. She entered the conservatory on her piano teacher’s recommendation at the age of twelve. As a Jewish woman, she was obliged to break off her studies during the Second World War and flee Antwerp with her husband Alex De Vries. After the war, the couple performed together in Belgium and abroad, gradually building a career. In 1964, Tolkowsky founded the Alex De Vries Fund in response to her husband’s suicide. She used this fund to give financial and moral support to young musicians in Belgium. Residential activities and concert evenings at her home supported more than a thousand musicians. She gave an interview on Radio 4 for the Queen Elisabeth Competition in 1981, talking about how gruelling these competitions were. After founding her fund, Denise gradually stopped composing. No compositions by her dated later than 1966 can be found.

Jacqueline Fontyn (1930) is a composer, pianist, conductor and music teacher. She has had a long, varied and highly successful career, receiving great international acclaim. Her style is multifaceted, using techniques such as aleatoric and twelve-tone composition, but her main focus is form.

These stylistic choices make her one of the pioneers of contemporary music in Flanders. In 1964, she was the very first woman to win the Queen Elisabeth Competition for composition.

Although Nini Bulterys would go on to win second prize in this competition two years later, it would be 2008 before another woman won. Her achievement entitled Jacqueline to compose the compulsory work for the semi-finals of the piano competition in 1964.

In 1976, she composed the compulsory work for the finals of the violin competition. She went on to have a long, varied and highly successful career, receiving great international acclaim.

A new perspective

Music history – or history in general – has not been kind to women who wanted to compose, and neither has historiography. A lack of publishing was not the only reason for so many scores to be lost; there was also a lack of interest. Often little source material concerning these women can be found, or none at all.

Since 1970, the debate on music history has been raging: how it is conveyed to us and what the position of women in this history is. It is no coincidence that this occurred in parallel to the second wave of feminism that, among other things, aimed to get women out of the kitchen.

The essays ‘Why have there been no great women artists?’ by the art historian Linda Nochlin and ‘And Don’t Call Them Lady Composers’ by the composer Pauline Oliveros question historiography and the accompanying canon, which have been created from a male perspective.

In the 1980s, New Musicology emerged and engaged in dialogue with various other disciplines, including sociology, feminism, anthropology, history and gender studies. This school of thought approached music history from new perspectives and explored the historical narratives that played a role in the creation of the canon. We cannot change the past, but we can change the way we look at it and deal with it.

Social and aesthetic shifts

The social changes in that period also meant that opportunities to fulfil certain roles became more equal. That did not happen overnight. One by one, women began to take up roles that had previously been reserved for men. For example, Josée Vigneron-Ramackers (1914-2002) became the first head of a music school. She also conducted the Limburg-Maas Symphony Orchestra, another position that had only been occupied by men for many years, and composed works including orchestra, chamber and choir music. Mieke Van Haute (1948) was another early head of a music school. Like many other Flemish composers, she combined composition with a career in musical education. Her music is characterised by a concise musical idea that functions as a thematic line throughout the composition. She later also became a director of advocacy organisations such as the Flemish Music Council.

As the social changes of the 1960s and 1970s took hold, much also began to shift in the field of Flemish music. New music gradually emerged from the fifties onwards, thanks to composers such as Jacqueline Fontyn. Until then, the style in Flanders had mainly been Late Romantic or Impressionist, with the occasional foray into atonality. As far as we know, no women were involved in the purely electronic music that emerged in Flanders in the 1950s and 1960s. Things were different elsewhere, where various female pioneers pushed back the limits of music.

In French-speaking Belgium, Annette Vande Gorne (1946) is one of the leading figures in Belgian electro-acoustic music. She founded the Musique et Recherche centre in Brussels and started the studio Métamorphoses d’Orphée in 1982. Two years later, she organised the Premier Festival Acousmatique Internationale de Bruxelles, thus confirming her role as one of the most authoritative figures in acousmatic music in Belgium. Within this musical current, the focus is on listening itself without distraction from the source of the music.

Sound artists and composers including Donika Rudi (1982) and Charo Calvo (1960) were taught by Annette. Fanny Tran (1949) is another early innovator in Belgian music. In May 1968, she and her ensemble Musica Viva presented concert happenings that already combined her own compositions, early music and slide projections. A year later, she went to study with Marcelle Mercenier (1920), a celebrated pianist and defender of new music, before going to Poland to specialise further. Improvisation plays an important role in her music, in sharp contrast to the immutable nature of the tape she uses. This has also led her to share the stage with the Brussels-based improvisation collective INaudible, as well as working with the SEM (Studio for Experimental Music) and Logos.

In Flanders, Moniek Darge (1952) is a proponent of the experimental aesthetic. She is a composer, violinist, performer and music box maker, and is best known for her live art performances. She specialises in soundscapes: audio landscapes in which environmental sounds merge into noises she produces herself. This is music that makes time stand on edge vertically, blurring the boundary between humans and their surroundings. She also experiments with non-European musical instruments and forms of musical experience in her work. She was a co-founder of the Logos Foundation, where composers such as Laura Maes (1979), Barbara Buchowiec (1963), Dominica Eyckmans (1967) and Liesbeth Decrock (1990) later also worked.

In the search for new timbres, smaller instrumental settings began to gain ground. Besides the economic advantages of working with a smaller group of musicians, this approach often also offered more room to experiment with specific combinations of instruments. Consequently, less and less symphonic work was written, and writing that type of composition was no longer a requirement to gain respect as a composer. The number of ensembles also grew, as did the opportunities for playing together and collaboration.

One of today’s most renowned Flemish composers is Annelies Van Parys (1975). She experiments abundantly with timbre in her music, but also combines the new music aesthetic with composition techniques from the past. In her search for new forms, colours and techniques, she works closely with several ensembles. Her works are premiered and performed in Belgium and abroad, by renowned ensembles such as ChampdAction, I SOLISTI, Collegium Instrumentale Brugense, Antwerp Symphony Orchestra and others. She has also created various music theatre productions with Muziektheater Transparant, including her first opera, ‘Private View’. Other composers familiar with the theatre and opera genres of music are Kaat De Windt, Hanne Deneire (1980)and Lente Verelst (1994).

Female composers are now better represented in choir music as well as music for ensembles. Erika Budai (1966) has a clear preference for the choir as a medium and gives her work a dramatic touch by adding harmonic colour and non-vocal elements. Noor Sommereyns (1982) also wrote a lot for choirs. She is not averse to dissonance, but often retains tonal underpinnings and strong motivic coherence.

At the end of the 1980s, there was a policy shift in subsidies from the Flemish Community. It benefited the creation and performance of new art music, especially by smaller ensembles. The cohort of composers in Flanders gradually became more aesthetically diverse, and simultaneously more demographically diverse. However, it should be noted here that little funding flowed directly to women. Ingrid Meuris (1964-2003), Kristin De Smedt (1959) and Petra Vermote (1968) belonged to a small and select group of women who received commissions from the established names in the Flemish music sector.

Further expansion

The number of Flemish female composers is still growing steadily. Names such as Ellen Jacobs (1996) and Lara Denies (2000) are appearing ever more often on concert programmes. There are various initiatives committed to highlighting new music (by women). The entirely female orchestra Virago only performs work by female composers and also commissions new work. There is also the project PIY (Perform it Yourself) by Maya Verlaak (1990), which aims to break down barriers by making the work of young, contemporary composers easily accessible to audiences.

The rise of composer-performers such as Elisabeth Klinck (1995), Ann Eysermans (1980) and Eveline Vervliet (1997) has enabled more women to claim an independent place in the sector. Composer-performers take charge themselves, which makes them less dependent on their network. The crossover with other artistic disciplines is also bringing in more new faces. Aurélie Nyirabikali Lierman (1980) combines radio art, voice art and composition in her work. She has her own large collection of recordings of rural and urban East Africa today, which she slowly transforms, in combination with other elements, into an ‘Afrique Concrète’. Aurélie started out as a radio maker before finding her way into classical music, but there are also movements in the opposite direction. Pak Yan Lau began her career as a composer and musician but is now increasingly exploring sound installations.

As multidisciplinarity increases, the borders between classical music and other genres are also blurring. This makes artists such as Liesa Van der Aa (1986) and Miaux (Mia Prce) (1982) difficult to classify. Other genres of music are also gaining greater respect. The term ‘composer’ no longer refers exclusively to the writers of classical music, but is also becoming standard in pop and jazz. An example is the collaboration between LOD and Nabou Claerhout (1993) that has been conquering the contemporary jazz scene for the last few years. With her debut EP, Hubert, Claerhout has gained a permanent place on the map as both a trumpet player and a composer.

Social changes and the expansion of the professional terrain have done more than merely ensure that more women work in the field. There are many other groups who used to be systematically excluded from Western classical music history. Although there were hardly any composers and musicians of colour in Flanders in the past, this has fortunately changed now. Figures such as Umut Eldem (1993), Shalan Alhamwy (1982) and Noah Thys (1992) – three male composers of colour – are each enriching the contemporary Flemish music landscape in their own way.

The idea that a composer is a Western white man who writes classical music is far from ancient history, however. The fact that we still often use the term ‘female composers’ proves that composing women tend to be seen as more of an exception than a rule. Women and minorities are still struggling to build careers as composers, due to a lack of representation and the prejudices associated with that. People need to understand why women and minorities have been absent from music history, and more attention needs to be drawn to those who have had musical careers, so that there are inspiring examples for new generations. People who see themselves mirrored in others are more likely to aim for a career as a composer.