Brussels. In search of territories of new-urban creation

Chris Keulemans (c) Sofie Joye

I want to get off at Central Station but the metro passes the station as though it didn’t exist. Onto the next stop, then. It is 9 p.m. The compartment is heavy with the heat of a long summer’s day. In a blur we get off at De Brouckère. Get back, get back! Heavily armed soldiers shout at us from the deserted platform to get back onto the metro. People reach for their phones. All of a sudden, 30 strangers form an alert collective. Western city dwellers in the state of terror. A photo on Twitter: a small plume of fire between the pillars of the Central Station. Someone wanted to commit an attack. He was shot down at once. Around me people are shaking their heads. They comfort each other. Are you alright, madam? Unbelievable, no? Bunch of bastards. Hold on – we don’t know yet who did it.

People who were avoiding each other’s gaze a minute ago are now looking each other in the eye. As though to say: I mean well, you can trust me, are you alright, do you not want to sit down for a minute? City dwellers together. Everyone shows their good intentions. The Arab-looking youths in the first place. To prevent any misunderstanding. When I get off someone reaches out his hand. One of the boys wishes me a safe journey. I’m in Schaarbeek. Walking down Paleizenstraat in the sunset, I ask myself: is it too frivolous to see these few minutes of urban panic as if it were a moment of theatre with only actors and no director?

A Soft cartography

This text is a report of a month in Brussels. No more, no less. The report of a month spent walking, talking and observing. At the invitation of Flanders Arts Institute and in particular of Sofie Joye, in charge of Diversity, Urbanity and Emerging Artists. Together with her colleagues and with Geert Opsomer – dramaturge, lecturer at RITCS and walking encyclopedia on interculturalism – she formulated the goal as follows:

‘A soft cartography of circuits that currently operate on the edges of the arts landscape, but are often important hubs of new-urban creativity. Not the mapping of these places, but the role they occupy in the network and how they collaborate, starting out from the perspective of the artist.

We need a different approach when monitoring the field. The tools we use today are rather static and study what is already there. Those tools aren’t yet equipped to fully observe the dynamics in the field and to evoke change. More attention is needed for the parallel circuits that are neglected in the current monitoring of the arts field, but where interesting innovations, networks and dynamics are taking place.

If we assert culture as a public good then we also have a responsibility towards the public, towards society and towards artists in the narrative we put forward. Like producing more daring accounts and from there, taking a critical look at the sector and at society.’

Joye and Opsomer also refer to Deleuze and Guattari, with their rhizomatic thought. During the 2015 symposium ‘City of Cultures Revisited’, Opsomer said that a new, adventurous form of cartography should start with a walk: ‘Strolling where the mood takes us, rather than relying on a fixed direction or restoring some form of central identity or norm for the arts.’ That is an invitation I gladly accepted. Wandering where our mood takes us. With the following underlying questions:

What are the territories of new-urban creation in Brussels today? In our cities we see a lot of places that present interesting cases of cross-pollination. Averse to parochialism, new alliances are forged between the arts, crafts, activism and the city.

How do these new places emerge? Who is part of them and who isn’t? What dynamics are at work in them? What alliances get sealed there?

Territories of new-urban creation. Not a groovy formulation, but a scrupulously chosen one. Not places but territories: the less clearly defined spaces that are traversed and crossed. Not artistic but new-urban: the dynamics of rapidly changing urban life, which besides a lot else also yields art, albeit in forms that are not immediately categorised as art. Not shows, exhibitions or concerts, but creation: the making instead of the made. Not quite the whole of Flanders or Belgium but first Brussels: the capital as concentration of an exploration that will expand rhizomatically to other cities and areas.

That exploration begins with a walk: the first steps on the road to the landscape sketch that Flanders Arts Institute draws of the cultural field in Flanders every five years. The 2019 edition will follow on from Transformers, published in 2014. It will again be replete with data, graphics, analyses and interdisciplinary overviews which Flanders Arts Institute excels at.

Our walk and everything that ensues from it could contribute something new to it: Flanders Arts Institute realises that it is based in Brussels, a city of which Flemish art forms only a part and where in every nook and cranny – including outside the established arts circuit subsidised by funds from the Flemish Community – a dynamic is at work that is going to expand, enrich and renew that circuit. This walk opens up the exploration of this field. With hopefully as a consequence: closer research into the objectives and methodology of the people, organisations and their practices as we come across them en route – and there are of course many more; further explaining the artistic strategy that the new artists employ; attention for the current policy context and the possible adjustments brought to it in the future. And that, in collaboration with the institutional and non-institutional parties involved.

‘What you are going to map during your walks through Brussels’, said Geert Opsomer, when we came across him under the fluttering awnings of the Romanian Café Tabs at the Abattoir market in Anderlecht, ‘is a psychogeography’. Not so much the places, but the connections, the networks, the dynamics. And then of the key players that we meet, the art to translate themselves from one circuit to the other, from one environment to the other: the art that every city dweller has to grasp sooner or later.

That is why, walking around a city I hardly knew, I started looking at the people on the street as translation-artists and at the encounters between inhabitants of this city as moments of theatre with only actors and no director.

‘What you are going to map during your walks through Brussels is a psychogeography’.

GEERT OPSOMER

‘Allee du Kaai is not theatre. What we do here is not art’, says Pepijn Kennis, one of the initiators of the non-profit organisation Toestand vzw. And yet they just won the Ultima, the Flemish culture prize in the category ‘Sociocultural work for adults’. Kennis is one of the three guides that Flanders Arts Institute asked to show me around; the other two are dancer Yassin Mrabtifi and choreographer Einat Tuchman.

If you spend a day walking around this extensive area along Quai des Matériaux with its old hangars, cobbles and patches of grass, you see one variegated composition after the other.

Reggae can be heard across the grass: music for everyone. There is beer for sale, including organic beer, as well as pancakes made on the spot by a Moroccan woman. Children and hipsters climb the brand-new climbing wall. Young families sit on the grass. Skaters ride the slopes of the park that they themselves built. More than 40 per cent of the people here are under 25 and would have been called foreigners 20 years ago. In the large hall there are a few people playing tennis and billiards. They are not in the way of all the other people here; neither do they pay a lot of attention to them. CollectActif is preparing the meal in the kitchen. Undocumented refugees and their supporters are cutting into piles of onions and vegetables – the market surplus, picked up at lunchtime. A few minutes later we are standing in line: soup, falafel, endives, couscous, carrots. Pay what you want; wash your own plate and cutlery.

In a corner of the hall there are two old sofas on a stage. A cross section of the city (senior, speech defect, unemployed, activist with humour, activist without humour) takes a seat. A hundred people listen and engage in a discussion about bobos and proles. The gap is too big, everyone agrees, and we have to do something about it. Later a brass band performs on the cobbles at the canal. The young trumpet player in overalls is excellent. The cross section dances to Balkan music in the setting sun.

Allee du Kaai may not be theatre, according to the initiators, but it is a performance. There is a collective director. The tempo is deceptively slow. Many of the narratives have neither a beginning nor an end in the show nor even within this theatre. For the visitor, that unascertainability is part of the appeal. The beauty also lies in the ever-changing compositions: from a visual perspective, the space, which offers panoramic depths from every corner, is never the same. The actors are all amateurs. That in no way detracts from their eloquence. They borrow the latter from the contrast with many of the other actors, with whom they do share the space but not the plot line. Allee du Kaai plays a refined game with the visitor’s expectations. Saying goodbye and walking out the door is difficult: something incredible can potentially happen here any minute.

New criteria

To observe new forms of creation, the observer must first look at himself. Who is the ‘I’ speaking here, what is his perspective, what criteria does he use? And is he capable of breaking open this self, this perspective and these criteria in such a way that he catches sight of more than what he recognises, more than what merely confirms what he already knew?

‘Perfection is not expected in Brussels’, I read on the first day of my stay, sipping a double espresso, while the morning light strikes Molenbeek. The speaker is Geert van Istendael, the eminent chronicler of this city, in Bruzz. New-urban creation is, I think, also what Van Istendael is talking about. ‘In Brussels people without any training speak daily four or five languages, with the means at their disposal, so that they use all the means at their disposal. They need to talk, because that dustbin has to go or that tap is leaking. What I am now saying is a small ode to the washed-up Brussels resident. Right, we need to ensure that they really belong, and that is still a big problem, I admit.’

That last sentence of his disguises quite some questions that you first have to raise if you want to talk about new-urban creation. Who is that ‘we’? What authority does that ‘we’ have to ensure anything? What precisely should that washed-up Brussels resident belong to? Who is that a problem for? And in fact who defines what the problem is? What gives someone the privilege to admit that he has not yet ensured something that others have not asked him to ensure?

What gives someone the privilege to admit that he has not yet ensured something that others have not asked him to ensure?

I myself therefore have to answer such questions before I set out on my walk. I am from Amsterdam. A 57-year-old man who is turning grey and with a certain fondness for sports jackets and who mainly got to know Brussels in recent years by acting as a moderator for Flanders Arts Institute at gatherings in the KVS, Kaaitheater, Bozar and the Beursschouwburg: the established order of Flemish cultural life in Brussels. The golden quadrangle.

In Amsterdam I managed and/or founded three cultural venues: Perdu, De Balie and De Tolhuistuin. I have published novels and essay collections as well as many articles about theatre, war, migration, cinema, football, music and cities. I have the stubborn habit of seeking new art in cities that have just survived a disaster. Sarajevo after the war, New Orleans after Katrina, Beirut after the Israeli air raids, Rojava after the liberation of Kobani. Because I believe that artists can reinvent the city. Even in a city that has not been destroyed, where perfection is not expected, but does permanently seem to seek bright mental leaps and unexpected connections – before big holes really open up.

I am not an academic. I studied Dutch language and literature for no more than six months. The city is my library. I prefer to write down conversations than to quote theory. For me, walking is the best form of research. Travelling in other cities, I have learned to postpone my judgement, especially when I stumble across art that emerges from a frame of reference that I don’t know yet. Beauty can take me by surprise from the most unexpected corners. At least as long as I manage to let go of a couple of the categories with which I grew up. And to realise that my type – male, white, average, and with considerable cultural capital –has for some time now no longer represented the uncontested, dominant standard for power and taste, certainly not in the young, multicoloured capitals of Europe of which Brussels is the prototype.

So I have to leave behind and reformulate a couple of conventional criteria and expectations conceived by the established order.

Every periphery has a centre

Naturally this walk starts out from the golden quadrangle. It is then just as natural to see Molenbeek, Schaarbeek, Anderlecht, Sint-Gillis, the Marollen and Matonge as the periphery. Unless you start there. Just as many of the new artists of Brussels do. When, one Saturday lunchtime, I walked through the huge market of the Abattoir in Anderlecht, amid thousands and thousands of people that did not look like me, the Beursplein seemed far away and insignificant. A newcomer automatically assumes that the place of his arrival is the centre of his new city. For car dealers from Africa, that is the Liverpoolstraat. For refugees, the Maximiliaanpark. For foreign civil servants and diplomats, the European Quarter. They draw the map of Brussels from the place of their arrival. That is how it works for cultural maps too. Pianofabriek, De Kriekelaar, Barlok or Zinnema: whoever starts there develops frames of reference that are just as indelible as someone who starts in the golden quadrangle. One person’s periphery is another’s centre.

A theatre without a roof and walls is also a theatre

Like everyone else, artists deserve controllable work conditions and security. Subsidies – the distribution of community money in recognition of a value for that same community – can ensure that. They offer the freedom to turn those dreams into work. They also lead to the congealing of that work. To its contextualisation and walling-in. Literally: the placing. Investing in the facilities to create art inevitably leads to the question of more investment. Once part of the urban landscape, the facilities require daily maintenance. The stage floor has to be replaced, the bar in the foyer has to be fitted with new beer pumps, the till has to be connected to the overview of visitor viewing habits and buying behaviour. All in order to remain of value to the community.

That fortification of the subsidised arts, inevitable and justified, cannot be transposed to the street without the proliferation of the imagination. Of art that is inventive enough to make use of the existing facilities. Empty walls, footpaths, parks, high windows, street lights, and the passers-by that every city offers for free. That is where moments of coincidence and beauty and protest emerge. They only ask of you not to recognise art only when it hangs on a white wall, moves under a sophisticated lighting plan or has asked for your attention weeks in advance. They emerge before your eyes and define themselves.

Artistic quality is more than artistic quality

A well-conceived dramaturgy, a technically perfect solo, an audience that has been struck dumb, subtle references to Western classics – I am used to such criteria as a measure of beauty and innovation. But there is more. If the city map is limited to junctions of reference frames and on every street corner I get to see moments of theatre with only actors and no director, then my acquired criteria of artistic quality evaporate as of themselves. Or rather: they are joined by new ones. I learn that moments that all contain beauty, emotion and radicalness – why I see art as essential – can consist of elements that no one would call artistic. In a big city like Brussels, politics, the economy, migration and the environment take part just as much of a role in the hyper-concentrated clustering of urban life into situations that I experience as great art. Bureaucratic aggression, the traumas of the refugee, the widow’s loneliness, the bravery of an 11-year-old with a headscarf, the sky-high burden of debt of a terminally ill unemployed person, the linguistic confusion of an Afghan chemist who can’t master French, the poisonous soil of an abandoned factory and of course the shock of terrorist attacks – they all play a role when I want to go in search of the territories of new-urban creation.

He twists his YHH cap and keeps pulling on his San Francisco T-shirt like a breakdancer on the verge of stepping into the cypher. Yassin Mrabtifi, my second guide, moves through the streets of Molenbeek as though a choreography were engraved in the paving stones. For him, houses don’t have corners but curves, each square is a stage, he avoids the gates of the metro – without a ticket – as smoothly as the torero avoids the bull.

The man who is now under contract with Ultima Vez learned breakdance, popping and locking as a 13-year-old in the Ravenstein Gallery. ‘The floor there was wonderful! But the police chased us away.’ That is why his crew moved to the North Station, where the escalators of the metro reach the surface. ‘We used to dance where the prostitutes turn left and the Eurocrats turn right. Locking and popping in front of Brasserie North Express: those high windows are perfect mirrors. And we did the cyphers on the marble floor next to the exit.’ The entering light forms a perfect rectangle, the dust particles twirling in the view onto Bolivarlaan.

Hip-hop, in its original form, is a culture of rules and respect. The cypher, the circle of dancers where everyone gets a turn, is a democracy you step into and then out of. In battles you can beat an opponent but not humiliate him. Each generation – and that comprises five or six years – passes on his knowledge to the next one. Each one teach one. Given the lack of academies and stages you grow up in the public space. Yassin didn’t even know that Ultima Vez had a couple of wonderfully equipped dance studios right in his neighbourhood before a friend took him by chance to an audition and Wim Vandekeybus immediately selected him.

He slows down when he takes us with him over the long, sun-speckled avenues of Elizabethpark. His body absorbs the doubts and tensions of the city surrounding him and seeks a form in which to express them. ‘I’m now working on my first solo performance, “From Molenbeek with Love”. I’m going to try to show the clichés that city dwellers exhibit in their interaction with people who do not look like them.’ He says this at the place where for years already he has loved to come and think and try out new moves: the broad steps of the Basilica of the Sacred Heart. The silence of the church at his back appeases him. In front of the high entrance lies a perfectly round marble floor. The city stretches out in the distance. Nowhere else in Brussels is the view of the sky so broad.

But it is time to go home. Yassin lives with his parents and sisters in a quiet street, around the corner from the café where the Abdeslam brothers planned the attacks in Paris. The sun sets above Molenbeek. It is time for the iftar.

We used to dance where the prostitutes turn left and the Eurocrats turn right.

YASSIN MRABTIFI

Borders

It is obvious, everyone who knows the city better has known it for a long time, but for an outsider like me it is almost shocking to experience how Brussels is marked by hard borders.

From the apartment where I am staying, on Vandenbrandenstraat, I can be at the canal in two minutes. I cross the bridge between Dansaertstraat and the Steenweg op Gent, between the centre and Molenbeek. What a world of difference. From the hipster beer brewery to the Islamic bridal gown shop. From the brick-oven pizzeria to the tea house. And this is only the beginning. Walking through Brussels is stumbling across borders.

Between languages

‘In Brussels people without any training speak daily four or five languages’, said Geert van Istendael, ‘with the means at their disposal, so that hands and feet play a big role’. The people’s versatility is this city’s miracle. But it could be made so much easier for them. A simple, eloquent example: libraries. Amsterdam has 26 libraries for about 800,000 inhabitants. The Brussels-Capital Region has about 80 for 1.2 million inhabitants. But in Amsterdam they grow into local meeting spaces, with access to knowledge in all forms. In Brussels I have to look for them.

The first library I find is a French-speaking one, close to the pretty Sint-Gillis Voorplein. I visit the Centre Culturel Jacques Franck. On a piece of paper on the wall there is an itinerary to the Biblio. Around the corner, in a quiet alley, I first walk past it. Then I push open a door and find myself in a cramped stairwell with a protected porter’s lodge. The adult section is on the third floor. There are rows of bookshelves and three computers. There are two other visitors besides me. There are 15 Dutch-language books in the section Livres en langues étrangères. Poland has 18.

Between administrative layerS

On 8 June, Yvan Mayeur resigns. As the president of the homeless organisation Samusocial, the burgomaster of Brussels received generous attendance fees for meetings that never took place. Some people involved speak out in De Standaard. They are furious. ‘Too much power is concentrated in the hands of just a few people’, says a backbencher from the SP (Flemish Socialist Party). ‘It is an oligarchy that is not held to account’. CD&V minister Bianca Debaets (Christian Democratic & Flemish party) goes even further. ‘The city is a state within the state.’ And it is governed by the French-speaking socialists of the PS (French-speaking Socialist Party). ‘With their addiction to power’, says the Groen Brussels MP Arnaud Verstraete (Green party), ‘they have become so disconnected from reality that they no longer even see that they have gone too far.’

Mayeur is one of the French-speaking socialists of the PS. Ten days later, the cdH (Humanist Democratic Centre party) withdraws from all the governments with the PS. That involves the Walloon and Brussels governments and the government of the French-speaking Community. From an administrative perspective, Brussels is paralysed from one day to the next.

The Brussels-Capital Region consists of 19 communes. A month is too short for me to look over all corresponding administrative levels. But the key words that I hear from all sides don’t lie: secrecy, corruption, clientelism, and lack of communication.

Between neighbourhoods

The first time I went looking for an ATM in Molenbeek, I walked the streets for an hour without finding one. Apparently the people in this area are not interesting enough for the major banks. This is only one of the symptoms that say something about the division of capital, trade, welfare, ethnicity and cultural development between the Brussels neighbourhoods. The city is richly endowed with physical borders: I feel the social differences in temperature on both sides of the Canal, of the moving traffic along Slachthuislaan, the sun-speckled lanes of Elizabethpark, the underpasses of the North Station, the marketplace around Zuidlaan, the train tracks above Ursulinenplein, the stronghold of the Palace of Justice. These dividing lines form hard demarcations. The differences per neighbourhood in terms of population, facilities and atmosphere are more deeply ingrained than you would expect in a fluid, multi-ethnic city like Brussels.

Between ethnic groups

‘I have a Belgian mother, a Moroccan father and a lesbian sister. I like Fela Kuti, Sufjan Stevens, Fairouz and André van Duin. And don’t forget Queens Of The Stone Age. Oh yes, I listen to Debussy in Bozar and PJ Harvey in the Koninklijk Circus. When it is sunny I read Virginia Woolf and Murakami in Dudenpark. I watch the best of Pasolini at the Cinematek. I dream of Istanbul when I stroll through Schaarbeek. I go shopping at the South market (and in Hema, at least I used to). I get invited for tea by my Tunisian neighbour and in Matonge I dance with friends from Kinshasa.’ Hans Vandecandelaere quotes the Moroccan-Brussels film-maker Saddie Choua on the first page of his thick, beautiful book, In Brussel: Een reis door de wereld (In Brussels: a Journey around the World). ‘Brussels’, he continues, ‘is experienced by a lot of residents and newcomers as very open and tolerant. The diversity is such that any dominant “national” culture behind which everyone has to line up to belong is pushed to the background. As a rule, you can be who you are.’

But that takes time. Serge Aimé Coulibaly, a choreographer from Burkina Faso who has been living in Brussels for a short while, told me: ‘When you go out to meet people, you don’t meet people. You can go to a café, but you’ll still be on your own. The best way is to take someone with you. If you start chatting to someone, the first question is immediately, What do you want from me? Always looking for an underlying reason.’

And of course the attacks of 22 March have only increased the urban suspicion. The terror brought deep divisions to light, including within neighbourhoods, ethnic groups and families. At the same time, a lot of people have opened themselves up. I often hear how a warm wave of curiosity and fraternisation rolled over the city. But now, one year later, dancer Yassin Mrabtifi says pensively on the steps of the Basilica: ‘Molenbeek opened up after the attacks. The people showed that they were ordinary Brussels residents. But the city rejected them – and now the atmosphere is even worse than before. More and more friends and women wearing the hijab tell me stories about explicit discrimination at work, in terms of housing, in the street.’

Ethnic enmity is typical of melting-pot cities like Brussels. But the city is resilient. And art plays a role in this respect. The people that I quote here are all three ambitious, gifted artists. Will they succeed in bridging the dividing lines? It won’t be simple. All these borders are also present on the cultural map of Brussels.

Border areas

Because I have to cross over so many visible and tangible borders in Brussels, no matter what direction I walk in, I soon feel like a world traveller. But also like a smuggler. The dividing lines are so hard that they give you the impression that you can’t step over them unpunished and thoughtlessly. A feeling of being involved in something clandestine regularly creeps over me. As though I were not only crossing a border but also breaking a law. Or at least disturbing the routine of others, the patterns of the city. There are moments that my curiosity becomes cloudy due to a certain nervousness. So that I sometimes, without any direct reason, involuntarily put up my guard.

What must this be like for others, who do not have my appearance, which is accepted almost universally as harmless?

That is why the border areas – the territories in a city that belong to everyone and no one, because they are on neither side but in-between – are a breath of fresh air. Literal border areas, such as Allee du Kaai or the Gemeenteplaats in Molenbeek, which so clearly mark the transition from one area to another. But also the formal ones: the areas between the institutions, with their own range and the surrounding territories, each in turn the periphery of another, each with their own centres and institutions. It is in those border areas that the interaction emerges between city dwellers that are foreigners to one another and who therefore keep translating themselves. Characters with meandering narratives, culture smugglers, always en route to cross over the dividing line.

Life returns to the Gemeenteplaats after a long, warm day of fasting. On the corner beside the Justice of the Peace Court, the door is open onto a reception hall where well-dressed families are listening to a fabulous singer and accordionist as they eat. On the other corner, Brass’art has opened since 22 March, the new Café Citoyen. The chef is still eating with his friends at a long table out front, but I am already given two glasses of rosé. Together with Moustafa I look out over the square that around midnight is still wide awake. Black youths enter to hear the reggae of Mic Mo Lion & Colorblind, children on bicycles are eating an ice-cream, older men in djellabas pass the café with a look that says that they don’t really know what to think of it, a young Muslim woman joins us briefly. Moustafa himself does not fast for the Ramadan. He has few reasons to believe in a god. Since a crash four years ago, the former law student has been unable to walk. He is in a wheelchair. His gnarled hands lie in his lap. He uses his little finger to operate his smartphone. He lives next door and divides his evenings between Brass’art and Café De Walvis, on the other side of the canal – Checkpoint Charlie, he calls the bridge, chuckling. We drink our rosé, talk about the demonstrations in the Rif, ask ourselves why the king perseveres in his silence and sigh that, despite everything, it is beautiful here, on the Gemeenteplaats in Molenbeek.

Border Crossers

‘We don’t want a bigger building’, says Marnix Rummens, ‘we want to fan out over the whole city’. The slender artistic director of Workspacebrussels stands like an exclamation mark with brown curls in his office on Onze-Lieve-Vrouw van Vaakstraat. This is next to the Kaaistudio’s, the splendid rehearsal room of the Kaaitheater, the main founding partner of this Brusselse Werkplaats voor Podiumkunsten vzw. On the upper floors of the stately building, performing artists and visual artists have the space to research new work. A small poster hangs on the wall: Objet perdu? Contactez Marcel Duchamp.

‘We hardly have any overheads – besides paid staff – but invest our liquidities of 300,000 euros per year as much as possible in artists. We don’t put our money in infrastructure, but follow our makers. In the black box but also beyond, from local parks to Bozar, from schools and churches to museums, retirement homes and the street.’ Rummens is just back from Venice where, in collaboration with S.a.L.E Docks, a local organisation for art and activism, he collaborated on Dark Matter Games. A group of 50 Belgian and Italian artists, writers and activists held a collective work week in April so as to inject the city in May with myriad artistic interventions in the public space during the opening weekend of the Biennale. ‘When you bring together artists with different backgrounds, you get a chain reaction of inspiration and ideas. But the context that S.a.L.E Docks offered us was also really important: people could set to work individually or collectively, they could make autonomous projects or respond to local initiatives such as an occupied park, a bottom-up housing project or a women’s rights organisation. For us it was about bringing the art world’s effervescent experimental underlying layer to the top of the iceberg.’ He stammers for a second, smiling, aware of the shaky metaphor. ‘For me it’s about creating that context and those production conditions. They are an indissoluble part of the artistic work. If we have attempted anything with Workspacebrussels, it is to make a place of connections, of cross-pollination, both among artists, organisers and society in its intriguing complexity.’

And that was no bluff, I am later told by Einat Tuchman and Gosie Vervloessem. The two artists, who, co-founders in 2013 of the action platform State of the Arts, were also present in Venice. In Praise of Waves, the 2016 exhibition inspired by Japanese culture, was unique, according to Gosie: ‘All of a sudden all artists were working together, at all levels. Down to doing the dishes. Talk about sustainable organisations …’ Einat adds: ‘You can currently detect a tension between a part of the arts scene that is focused on the creation of safe spaces, where artists can reflect on themselves and their own work, versus the artists who step out of their comfort zone, who are beginning to make work in other places. Marnix said that he also wanted to put on a show at a wedding, but that is of course taboo in the world of the Kaaitheater.’

So it seems. After a bubbling monologue of an hour and a half, Rummens suddenly says that he is going to leave Workspacebrussels in two months’ time. The Kaaitheater does not wish to continue with him. ‘Many art organisations preach renewal but in fact work conservatively. That’s also understandable for big houses that reign supreme in the traditional system. I think that the way in which we developed new networks and connections, and the more independent attitude that I took with artists, must really have been unwanted or felt inadequate to them. And yet I find that crucial, especially now that the traditional system of production and distribution is visibly getting stuck and crumbling. Day after day I am stunned by artists and the wealth of forms and formats that they imagine: installations, walks, urban games, interventions, you name it. And call it what you want, but these are new performative forms. As a complement to the black-box performance, that kind of work can happen outside the walls precisely, in all sorts of contexts and in relation to very different audiences. And yet that work is still treated marginally by discipline-based houses. And because we have built up the sector by discipline, there are hardly organisations that focus on that type of work. With Workspacebrussels I really tried, in complement to the autonomous black-box creations, to give artists the chance to develop and try out that alternative work. In dialogue with one another and with very diverse audiences and contexts. I believe today more than ever that this where there lies precisely a possible solution for the problems which we face as an arts sector. The talent of our artists, our aptitude for co-creation, is an invaluable wealth. But it has to be able to develop freely. Too many houses think from the existing infrastructure. And then you exclude a lot in advance already.’

Marnix Rummens is now continuing as the coordinator of the Buda Island in Kortrijk. The island will be populated by a whole series of organisations such as an arts centre, a workplace for design, the regional fund, but also schools, businesses and retirement homes. Even more than in Workspacebrussels, the cross-pollination between art, education, industry and the social sector will be central. It is an adventure that he wants to launch into with other artists. But even more so in dialogue with other creative developers, designers, teachers, architects, care providers, local residents, students, etc. The creation of stimulating production conditions, as part of the artistic work: ‘Because to me that too is dramaturgy.’

He will undoubtedly take his attitude to work with him. Crossing the dividing lines between disciplines and functions, art centres and the street, centre and periphery. Emblematic for an age in which precariousness dictates the choices of the artist. Almost everyone is now a ‘freelance entrepreneur’: a weighty term for an existence full of short-term contracts, hope-filled subsidy applications, searches for studios and residencies, temporary alliances. The freelance entrepreneurs who used to be called artists are working themselves into precariousness, but don’t have the time or (financial) space to build up lasting collaborations. The market’s diktat forces them into fragmentation, obsession with their own survival, and loss of concentration. It plays people against one another, encourages competition instead of coalition, and generates small-mindedness and territorial thinking.

Many art organisations preach renewal but in fact work conservatively. That’s also understandable for big houses that reign supreme in the traditional system. I think that the way in which we developed new networks and connections, and the more independent attitude that I took with artists, must really have been unwanted or felt inadequate to them.

MARNIX RUMMENS

Einat Tuchman and Gosie Vervloessem know all about it. I meet them on the 25th floor of the WTC, which rises above the North Station and Maximiliaanpark. On the ground floor is the Office of the Commissioner-General for Refugees and Stateless Persons. One floor up lies an abandoned shopping centre. It looks like a relic of early-capitalist dreams that has gone under. There are sculptures in the deserted corridors. The Centre Commercial Hellénique is for sale. The Taverne WTC is barricaded with its own wooden furniture.

High above that, 65 artists, designers and architects have set up affordable studios in boring offices with a priceless view. With State of the Arts, during the first wave of cultural austerity policy in 2013, Tuchman and Vervloessem politicised the arts sector with debates and demonstrations. Time was of the essence. But after a while, it was mainly about who had to do what and with what budget. ‘The cultural institutes’, sighs Tuchman, ‘work so much apart and they are so sensitive to criticism.’

Here in the WTC there is no longer talk of a collective. In the summer of 2015, when the artists saw the masses of freshly arrived refugees hang around the park below, they went down to do some volunteer work. Initiatives such as Cinemaximiliaan emerged. But after the attacks in 2016, there was no such reaction. Vervloessem: ‘A lot of artists said, “We don’t have to solve everything, surely?”’ Today the atmosphere is no longer political, but pragmatic. The tenants communicate mainly by email and then about matters such as the shared cost of the cleaning staff. A question of precariousness.

Tuchman, my third guide, does not have a studio here. She has danced with Les Ballets C. de la B., Victoria and Needcompany, choreographed her own shows, but is increasingly distancing herself from the arts world, which she no longer sees as a potential space for social reflection – and moved soon after the attacks to Molenbeek, where she is experiencing how you build that up, trust between strangers. ‘Brussels is a tribal city, very divided, it is difficult to bring people together. And yet, after the attacks I came across a lot of people who said: “We’re here, we’re Belgians.” An exercise of the will, made with pride.’ She founded Espacetous vzw and began with a street party. ‘That alone already means crossing so many invisible borders, between people, between groups!’

The cultural institutes work so much apart and they are so sensitive to criticism.

EINAT TUCHMAN

To earn a place in a neighbourhood which has learned to be suspicious, everything was against her, she laughs: she is a woman, an artist and from Israel. But the first time I saw her at work she was dragging tables in front of Wijkhuis Libérateurs on Maasstraat for the community party she was organising with her Espacetous vzw. In the middle of the street there were shuffleboards, a football table, a pancake stall and a small stage. The DJ was playing rai. The programme was all over the place. Einat laughed nervously. ‘No one is on time’, she said. ‘A given time is not set in stone here.’ I joined the neighbours: six Armenian men in shirt-sleeves who were fond of laughing and who were grilling chicken legs and offering me vodka. Children and adults crossed their own street as though they no longer recognised it: without cars and full of neighbours which, at best, you acknowledge on a normal day as you walk by. The atmosphere was relaxed but also uncomfortable. It took a while before they understood that the woman with the black curls, an artist from Israel, had in no time turned the unremarkable street which they lived on into a boulevard of possibilities, simply by saying that it was possible.

A couple of weeks later we drink coffee at Le Palais de Balkis, a spacious and impeccably arranged halal butcher shop in Molenbeek. We talk about trust, the building of new relations and the difficulty of remaining faithful to that in a city where no one stays on the same spot for long. She regularly takes other artists from her network – Workspacebrussels, a.pass, RITCS – into her neighbourhood. She watches them enthusiastically get acquainted, play, design, think along – and then disappear again. Local residents are invited to step briefly into an artist’s fantasy. The most courageous put aside their reservations and take up the challenge. They share their dreams and memories. The more open-heartedly they play along, the more they are encouraged. For a brief moment, during the show, they rise above the nameless everyday existence. After that, the emptiness often strikes again, all too often. Their new artist friends have moved on to the next project. In the neighbourhood there remain people who have exposed themselves for a moment, who have given their trust, have crossed their own borders. How confusing must it be to then have to lock yourself up in your own routine on your own?

That cycle of meeting, opening up and sobering up is something Einat wants to break through. Not for nothing has she settled in Molenbeek. She is staying. Because she wants to earn the hospitality of strangers.

‘The city doesn’t exist. The city is a sum of performances that are executed day after day by about the same people that do about the same thing – or not.’ The city as a set of performances – only actors and no director: the introductory text of Mapping Brussels immediately speaks to me.

Mapping Brussels, a journey of discovery through the city with the most diverse artists, is going to take place in September. It is an initiative of Gerardo Salinas, one of the three city dramaturges of the KVS. In their new season paper, filled with an exciting and superdiverse programme, Salinas writes under the heading New Urbanity: ‘Thanks to urbanisation, waves of migration and new technologies, our artistic spectre has been enriched immensely. New artistic practices emerge, among others from people who have been moulded into artists in another country and autodidacts who often experiment with new forms and art languages. The lion’s share of that fresh artistic talent is not in contact with our strong artistic sector, however. As a result, in many cases these new practices remain invisible to them, not readable. And in the same way, the established arts sector is invisible to artists from the as yet uncultivated artistic fields. It is not easy to connect both artistic realities. Yet both have much to learn from one another and mean a lot to one another.’

Salinas, the former artistic director of the Mestizo Arts Festival, is now an institutionalised border crosser. One Monday morning in the theatre café on the Hooikaai, Sofie Joye and I talk to him about his own form of soft cartography. ‘It remains ambivalent’, he says. ‘Flanders Arts Institute and the KVS do the mapping as an invitation, but perhaps also out of a need for overview and control, so as not to be blindsided.’ He speaks at the pace of someone who thinks, day and night, weekends and weekdays, aloud and passionately about the city that changes constantly. And the Argentine-born himself comments on his monologues: ‘My tendency to turn Spanish words into Dutch words is pathetic slash charming.’

Thanks to urbanisation, waves of migration and new technologies, our artistic spectre has been enriched immensely. The lion’s share of that fresh artistic talent is not in contact with our strong artistic sector, however.

GERARDO SALINAS

He is on a mission. ‘The invisible talents come from self-developed organisations. The mezzo level. That’s the one we have to help cultivate. That is my battle. In doing so you also bring the institutes themselves up for discussion. As an urban theatre we can’t produce everything ourselves. But we can support centres and workshops and research. If you really want to invest, then do so with space, legitimation and money. Those are my criteria.’

We are talking about the Theaterfestival, in which Mapping Brussels and the presentation of our soft cartography are programmed on the same day. ‘Yes, the festival is beginning to come unstuck from the established order. The mental masturbation of a Roman Empire that doesn’t realise it is crumbling. Beside the State of the Union we should also hold the State of the City there. Not in a fringe programme, but on the opening night. Not as guest, but as host. So that we can frame our story ourselves.’

We quickly think up a plan for a joint day programme during the Theaterfestival. A day about the new art practices of Brussels, including the presentation of the youth collective Transfo Collect. Salinas runs on. Sofie and I cycle to Schaarbeek.

Kito Sino lives on Rogierstraat. Visual artist, Syrian Kurd, former communist, former illegal alien, bon vivant, host. One of the many things in Brussels that I cannot reconcile: behind all those front doors lie concealed spaces that, taken together, are larger than the city itself. I am daily surprised by the volumes that open up before me. Kito lives next to a small courtyard. His studio is behind a garage door. I enter an oasis of colours and carpets, decorated pillars and a high box-bed. His art stands and hangs everywhere: paintings, installations, sculptures – and a framed selection of his trademark: meticulous, allegorical pen drawings on the reverse side of 17 years of rail season tickets. En-route art, which emerges as he travels: he has suitcases full of them.

But if Kito is home he receives guests. The last time I visited him these guests included a Palestinian student, a Syrian photographer and a Canadian film-maker. ‘My father was the village elder. Everyone who called in at our village was expected to visit him. And could stay with us if they wanted to. As a boy I always served tea to utter strangers and learned never to ask about the reason of their visit. I still do so.’ His name has circulated among newcomers in Brussels. If you have artistic aspirations and no objection to wine and music, then head to Schaarbeek, to Kito.

A bit later we visit Luc Mishalle, the saxophonist, band leader and born border crosser. In 1982 he planned to set up a theatre school in Nicaragua, at the time of the revolution. But the ramble of his life led him elsewhere. In England he played with Ghanaians. He attended overwhelming wedding ceremonies in Casablanca and fell in love with the atonal trumpets of the Gnawa. With a group of Turkish musicians he has played Gilgamesh 120 times. He programmed the Antwerp-Moroccan big band Marakbar during Antwerp ’93 in opposition to the Vlaams Blok. In Brussels he set up the Zinneke Parade, on both sides of the canal. And his MET-X is now included in the Arts Decree as a production company and participation venue, words which he utters with the tiredness of an artistic director who looks forward to playing all the harder after he has retired. Rewarded this year with the Princess Margriet Award of the European Cultural Foundation, and unrelentingly driven to keep circulating as a saxophonist outside the American standards, to remain free and European, new-European of course – and so now again overcome by the Brazilian-African orchestra that he is building up here, two musical styles that are related to one another on either side of the ocean, and here in the Marollen literally live opposite one another, on either side of the square.

‘Traditional music groups also see that their public remains limited to their own community – it is only when they try out mixed forms that they get a more mixed audience. Except that: the established arts sector doesn’t pick them out. They hardly get programmed. In that respect we really are a neglected field in Flanders. A solid brake has been put on over the past 15 years.’ In a recent interview with rekto:verso he puts the blame not only on people who are preoccupied with ‘their own people’ – ‘What do you mean by “own people”? Surely we are all our “own people”? That such a thing still exists!’ – but also the Flemish subsidy policy, and then especially ‘the rigid way in which people hold onto the traditional criteria of “artistic quality”. When we were appointed with Al Harmoniah as Cultural Ambassador of Flanders, some people from the field found that scandalous. Our way of playing did not meet the criteria of artistic quality that they used for competitions and applications. You notice that also in the advisory committees for subsidies. Under Bert Anciaux there were ten points on which we could evaluate artists, among which diversity. But that generated a discussion in every committee: did “diversity” weigh as much as “artistic quality”? In fact it’s all quite sad: that there is a cultural elite that is holding back change, while that mix is becoming quite natural precisely in what they scornfully call “commercial music”. If that doesn’t change, the subsidised arts are digging their own grave.’ A Roman Empire that doesn’t realise it is crumbling. A feudal system. That is digging its own grave. The border crossers who know the institutions of the established order know that the art of the city cannot blossom without subsidies – the distribution of community money in recognition of a value for that same community –, but they also recognise that that set of performances would suffocate if it became fortified within those institutions. That is the quandary of the culture smugglers. What they share is a restlessness. The hurried realisation that they are expected on both sides of the border. They must struggle to be allowed to party and they must party to be able to struggle.

As furious as Mishalle sounds about the inertia of the established order, he played no less joyfully with Ago! Benin Brass last week at the Plazey festival in Elizabethpark. They stood on the wooden floor, among the people – who were immediately won over. And completely so when Monsieur Luc, that tireless matchmaker of musical styles, after having blasted pleasantly for a while, suddenly rocked a ripping atonal solo across those effortless rhythms.

The border crossers who know the institutions of the established order know that the art of the city cannot blossom without subsidies but they also recognise that that set of performances would suffocate if it became fortified within those institutions.

Plazey was disarming. It was a mild Sunday evening. At one stand you could get a mojito, at another you learned something about Voem Brussel and the emancipation of Muslims. It was Eid day. That is why a blonde fairy was spinning candy floss for the Muslim children. This is a festival where amateurs of music from all quarters of the world drink themselves rosy and where girls without headscarves dance in front of the stage while their mothers in hijabs watch on, smiling. It is also a festival at which you feel how much effort everyone must make to show that they take no notice of the cultural barriers that society puts down before them. People smile more emphatically than is necessary. They clap harder for music that they do not really understand. They are happy in advance to mix with this diverse company and radiate that feeling too.

Souad Massi embodies what Plazey stands for. Sweet but serious. Multilingual by nature. Melodious and eclectic. The Algerian sings her own compositions in French, English, Tamazight and Arabic, compositions which sound as though centuries ago already they hung in the sky above Andalusia. The public, now certainly a thousand people standing, sitting and hip-swinging, melts with the first notes already. And yet, after 20 minutes, I slowly walk out of the park. There can also be something sad about so much good will. At least, a certain melancholy overwhelms me when the peacefulness that should be the most natural thing in the world has to be underlined with so much emphasis, in each smile and nod, because the normal has become rare in this world.

The music dies out behind me. On the broad Leopold II-laan, called after the murderer of the Congo, the immaterial pressure of the city, with its plodding passers-by and averted gazes, strikes one as almost salutary.

Community centres and centres culturels

Every periphery has a centre. Culturally speaking, seen from the established order, that should be the community centres and centres culturels. They are spread out over the whole city: 22 Dutch- and 12 French-speaking ones plus 13 Maisons de Quartier (community houses) and at least two Huizen van Culturen (culture houses). I visit nine of them. Not during the high season: these are official organisations, it is June, the school holidays are starting, the year’s programme is coming to an end. But still. Each time I am struck dumb by the spaces behind the front doors: entrance halls, interior courtyards, dance studios, concert halls, exhibition spaces, classrooms. Two things are pretty much present everywhere: commissioned positive graffiti on the brick walls of the interior courtyard and closed pianos somewhere in the corridors or stairwell. The nicest one is in the bar of Centre Culturel Jacques Franck in Sint-Gillis. A sheet of paper lies on the dusty piano: Ne pas toucher svp.

Most of the centres appear equally inviting and dismissive. I can’t count the theatre groups, bands and hip-hop crews that wouldn’t do anything to be able to rehearse and perform in these venues – often equipped with full light and sound installations. I know whole theatres in Amsterdam that have to make do with half the space. But in the Curo-Hall, the house of social cohesion in Anderlecht, it seems as though we have walked into an empty church, including half-decayed frescos of local heroes on the high walls; it is only in the last room that we meet a living being. With Yassin Mrabtifi we sneak through the monumental, extinct spaces of Huis van Culturen in Molenbeek without being spoken to by any one. In Centre Culturel Jacques Franck, after the rousing display of leaping local residents in the entrance hall, I come across a most friendly caretaker who tells me that all other rooms are closed. Einat Tuchman has to move heaven and earth to open the high door of the Maison de quartier Libérateurs, in the middle of the Maasstraat, during her street festival that takes place right before its door.

Fortunately, things can be different.

On the inner courtyard of GC de Kriekelaar, the talk is about superheroes. The beatboxers, dancers, film-makers and rappers of Transfo Collect gather here every other Sunday at lunchtime, under the high trees or in a rehearsal space in this walled-in paradise of Schaarbeek. This coming season they plan to turn into Superheroes in Real Life. They want to get out into the street, in their costumes, as saviours of reality.

At the previous meeting they read, with coaches Geert Opsomer and Aurelie di Marino, the book by philosopher Franco Berardi, Heroes: Mass Murder and Suicide. They talked about James Holmes, the boy who called himself The Joker, complete with orange hair and maniacal grin, when he shot dead 12 people five years ago in Aurora, Colorado, during the evening screening of The Dark Knight Rises. Like many high-school killers and suicide bombers, he saw himself as the saviour of a corrupt society.

Can it be otherwise? Can a superhero fire off question marks instead of bullets? Can they ask you where it hurts? Can they let you see that their costume hides nothing more than their own vulnerability? That is what the performers of Transfo Collect are going to research after the summer. Theatre that hits the street to bring to light the city’s doubts. Aurelie could immediately imagine it: Batman, Hulk and Wonder Woman presenting themselves on Brabantstraat and Liedtsplein to perfect strangers: ‘Good morning. We’re superheroes. What can we do for you?’

I look around the table. Abdullay, Giovanni, Bilal and the others are in deep concentration, seated on red plastic chairs in the midday sun. Are these the washed-up Brussels residents whom Van Istendael was talking about? Brussels doesn’t expect perfection. Not from its wise writers. And not from its vulnerable superheroes.

At Zinnema, recommended to us by Yassin Mrabtifi who was given space here, we are received by director Nathalie De Boelpaep and artistic coordinator Jan Wallyn, who began here as a choreographer. Zinnema, currently under renovation to make the entrance, foyer and main hall brighter and more accessible, is officially called the Vlaams Huis voor Amateurkunsten te Brussel (Flemish house for amateur arts in Brussels) but calls itself the Open Talentenhuis in Brussels. And they are also active in collaborations with the Periphery of the Region. Anderlecht is their neighbourhood, for which they set the doors wide open, but Brussels is their city. They work together with established and less established initiatives in the fields of theatre, dance, cinema and music. ‘The building is the property of the Flemish authorities’, says De Boelpaep, ‘we don’t pay rent and so can put all our spaces at the disposal of people who come to us with ideas. We have a turnover of 1.3 million, we have 24 employees, mostly Dutch-speaking, but we try as much as possible to work in both languages.’ Most dancers, theatre-makers, choreographers, film-makers and musicians here are amateurs, ‘but this is a lift: the young talent that works here can also progress to training courses and the professional circuit. We offer them tools: professional coaches, support in production and communication, help with subsidy applications.’ Wallyn: ‘Five times per year we have someone here in residency, just as I joined: then you get a rehearsal space, coaching, help when scouting your cast, extra attention for communications.’

I haven’t seen a performance here, but you can feel the energy. Pupils and senior citizens, white and black, Dutch- and French-speaking – Zinnema is in all respects a product of government policy, with all the accompanying objectives, but at the same time you notice the difference here: when there are real people at work and not clientelists, then a lot is possible in the spaces that are so numerous in Brussels. I have wandered through the corridors and recording studios and stairwells and nowhere did I come across a dusty piano.

When there are real people at work and not clientelists, then a lot is possible in the spaces that are so numerous in Brussels.

‘Because no one sees us, we are free to say anything.’ That is the motto of Citylab. We meet Angela Tillieu Olodo, Samira Hmouda and Hari Sacré: young, wise, ambitious and idealistic. So far during my walk I have not seen the paradoxes of the new-urban creation at work so explicitly. Their tale is bursting with them: on all sides you feel that the old system, that crumbling Roman Empire, is here on the verge of being replaced by something new. Has to be replaced. But hasn’t yet been replaced.

Because no one sees us is an ironic statement for a club that excels in the production of short films made by Brussels youths: the most visible and sharable art form. In fact Citylab is saying: if no one sees us, then that is because no one wants to see us. Us: an ever-growing number of young, often self-taught street-style comic-strip storytellers, who do not fear, but on the contrary dive into, urban heartache such as police violence, racism and Islamophobia. Free to say anything is just as ironic: yes, the films are unashamedly candid, but the story of Angela, Samira and Hari is full of policy friction, institutional awkwardness and the fight against stigmas.

We add something to the formal order’, says Angela about their collaboration with the golden quadrangle of the Brussels arts, ‘but at the same time that order is afraid that we are harming the artistic quality of their programme.’ It is the same false equation which Luc Mishalle pointed to: diversity versus artistic quality.

The third edition of their film festival System_D took place last year in the KVS, which gave them carte blanche. ‘A real stage, the red carpet, a nice venue, badges, prizes, recognition – and all that for the first time.’ But also: constant communication problems. Angela, who comes from the public outreach department of the KVS, grins. She knows how difficult it is for the formal sector to involve the informal one. ‘We had to provide all the information months in advance. But our public doesn’t buy tickets in advance. Their publicity texts didn’t suit us. And our promotional pictures didn’t fit their house style.’ Gerardo Salinas has already put it down on paper: ‘It’s simply impossible for an elephant to pet an ant.’

At present Citylab is providing two young makers to Mapping Brussels, again in the KVS, but now with Salinas. Both sides have learned. If the two makers do not end up too subordinate to the advanced makers, if they are allowed to make mistakes, then this can be a valuable meeting.

But in their own house too it is a question of treading on eggs. Citylab is part of Pianofabriek, a community centre in Sint-Gillis. Here too: room after room, rehearsal spaces and recording studios. This is where Stromae recorded his first tracks, where Yassin Mrabtifi and Pitcho Womba Konga made their early work. This really is more a factory than a forgotten church. The agenda is crammed, it is a struggle to get a space. All employees share a vast office, but formally the division remains strict. Kunstenwerkplaats Pianofabriek works with artists who have some training under their belt, Citylab precisely not. Other subsidy streams, therefore. On the website of Pianofabriek it is said that Citylab works with ‘youths who want to provide a social-artistic answer to political problems’. In other words: no art subsidy is necessary here, these youths can make films and performances, but are not going to become a house company, so art training programmes don’t need to scout here. Citylab falls in the category of community work: regardless of the quality of the films, regardless of the fact that many of the youths visibly incorporate international influences and even connect with the countries of origin of their families. In July, Samira is heading with System_D to a festival in Dakar, Senegal. After the summer, the trio is going to continue to break open the old system.

Community work, social-artistic work, participation: these are policy categories through which a lot of the new-urban art that I encounter is prevented from developing. The artists themselves have already outgrown all those little pigeonholes. It is now up to the policymakers, but also to the community centres and centres culturels to choose: are they going to remain passive providers of leisure activities or are they going to take their responsibilities as centres of new art seriously?

It is precisely a year ago that, on the square of the Abattoir, between the stacks of tomatoes, shoes, watermelons and mobile telephones, the first colony of the République très très démocratique du Gondwana was proclaimed. Standing between the market stalls, ambassador Roch Bodo Bokabela addressed the TV cameras: ‘Life is good in Gondwana. Because everyone is happy in Gwondana. Problems are solved smoothly.’ And that thanks to President Mamane, who is acclaimed by the population as the actual inventor of democracy – regardless of what the Greeks may say. His country has been declared the nation with the most sunshine: 412 days per year. Recently it was revealed that 200 per cent of the Gondwanese are going to vote for the re-election of their president. That will happen by referendum. Today he used his daily blog to explain how such a thing works: ‘The people cannot say no. That is the referendum. If you vote yes, it’s yes. If you vote no, it’s still yes.’

In his everyday life, ambassador Roch is an actor in the Congo. President Mamane is an actor in France. Gondwana at the Abattoir was a theatrical collaboration between Johan Dehollander, Geert Opsomer, Aurelie Di Marino, Congolese actors and students of the RITCS. It wasn’t a classical performance. Spectators received Gondwanese passports and coins. From the moment of their arrival they were citizens of a very, very democratic republic. They were all the lead actors and there was no director to be seen.

‘We wanted to build a heterotopia within the heterotopia’, says Aurelie di Marino, ‘a city within the city’. We are sitting in Café Tabs on the square. The banner above the door advertises Romanian specialties. We already met Aurelie as the coach of Transfo Collect. She studied literature at Leuven University and the Sorbonne, and theatre directing at the RITCS. At present, together with 16 others she is part of the Koekelbergse Alliantie van Knutselaars (K.A.K.), which has moved into an empty building close by. On the square she is in her element. Her grumpy tone barely camouflages her passion for theatre as ur-democracy. In Flemish dialect she recites Gramsci as easily as Deleuze and Guattari.

‘We rehearsed in the field, between the market-goers. The singer called Starlet rehearsed Congolese songs with us in Lingala. People were open to the illusion, to the game – that opens the codes and laws of such a place. The passport legitimised the crossing of the border between strangers. To quote Beuys, it became a social plastic. We showed how you can break through the dominant logic. It’s always possible, if only you develop an alternative logic.’ And that became the République très très démocratique du Gondwana.

Next week K.A.K. is presenting La Soirée Télé Partagée in their building on Liverpoolstraat: a range of talent from the area will show its arts in the vast display windows. On the programme: Dada Speech, amateur rap by Mich, chansons of the children’s choir, Farbod’s kitchen. ‘Horizontality is not only ideology’, says Aurelie. ‘It is a lifestyle, a practice. That is how it emerged and that is how it remains. Our teachers at RITCS asked us: are you all really going to help one another along or is everyone going to level everything down? Turns out: neither. Something else emerged, a collective subconscious. We divide up all the work, but as soon as you hold on to something too strongly, you have to let it go again. K.A.K. is an honest factory: a structure that can never get so static that it pushes the desire aside, because then everything would be lost.’ A structure in which you can say yes but also no, a state without borders, a democracy in the form of a market square.

The heterotopists

When Luc Mishalle fulminated about the cultural elite holding back change, Sofie said: ‘That also leads to parallel circuits, which seek their own path and turn down the invitation of institutes.’

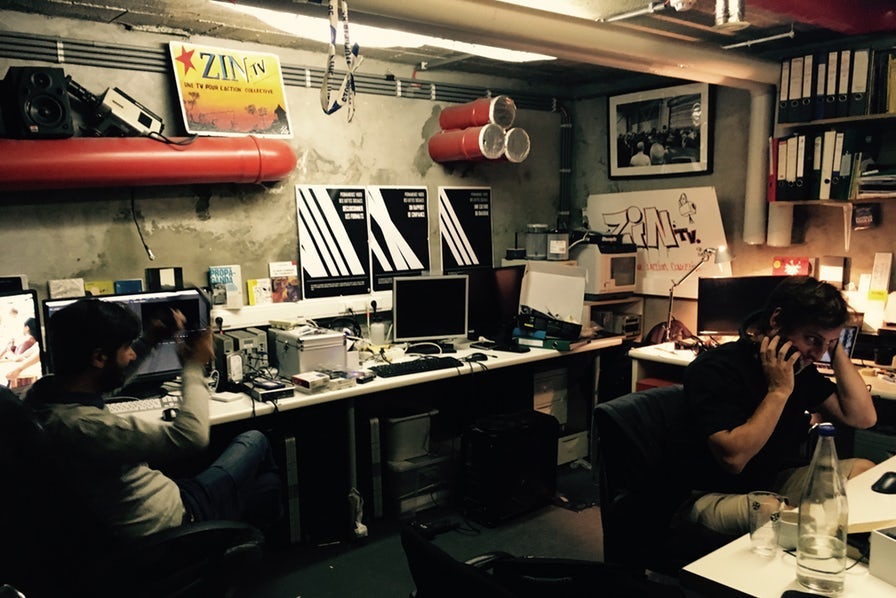

Those parallel circuits with the stubborn heterotopists, who are now organised loosely, now collectively, are something I encounter more and more on my walk. The sincere factory of K.A.K. in Liverpoolstraat, Transfo Collect in the paradise of Schaarbeek, the audiovisual storytellers of Citylab, the cross section of Allee du Kaai, Kito Sino and his guests, the poppers and lockers in front of the high windows in the North Station, the Dark Matter Games of Workspacebrussels, the wind-instrument players of Ago! Benin Brass, the pragmatic precariat of the WTC, but also: the people of Cinemaximiliaan who screen films about migration and the wide world for newcomers in Brussels; the nomadic ship La Tenace of Gerda Goris alias Madame Belga and her daughters Saar and Rose, who offer a stage to musical collectives who experiment with new ways of surviving economically and culturally; Cultureghem on the concrete urban plot of the Abattoir; LeSpace of Rachida Aziz and co., the experimental field for the cultural centre of tomorrow.

Those parallel circuits with the stubborn heterotopists, who are now organised loosely, now collectively, are something I encounter more and more on my walk.

Before I leave, I pass by Brass’art one last time, the Café Citoyen of theatre-makers Mohammed Ouache and Sanae Jamaï, who, a couple of evenings earlier, put out the iftar on the wooden tables on the Gemeenteplaats while inside they showed the merciless African-American documentary 13th by Ava DuVernay. This time I walk into their small exhibition space, one door down. The exhibition Children’s Tales? has just been visited by a group of local residents with disabilities, some in wheelchairs. They stare mesmerised at the seven video projections placed inventively in the space. Curator Zsolt Kozma is a border crosser with a robust record of service: the small Hungarian has worked in Europe, Asia and the United States, but talks about this exhibition as if it were his first. The artists that he is showing here come from India to Canada. He has given their work the sequence of a life story: from the moment we learn to see the world around us to the moment we play the lead in our own feature film.

The exhibition is both highly accessible and very subtle. No one has dumbed down video art for the inhabitants of Molenbeek. Kozma demands as much from himself as from his visitors. And both are the wiser for it. Suddenly I understand what connects all these heterotopists. The eye of the artist. The artist as director. The director of reality. The reality that presents on every street corner moments of beauty, emotion and radicalness. For whoever is willing to see. For whoever is willing to break open his self, his perspective and his criteria. And to see that artistic quality is more than artistic quality.

It brings to mind the exercise that Aurelie Di Marino put to the washed-up Brussels residents of Transfo Collect. On that warm midday under the trees, she found it difficult to formulate properly what she still found lacking in their plans for the Superheroes in Real Life. ‘Something is still missing’, she frowned. ‘Theatre is content. Content is what we have experienced. And that is more than biographical data.’ She looked around the group. The faces revealed pretty much all the city’s cultures and mixed cultures. ‘We inject our real lives in the theatre. We can all do that. But now we also have to inject that theatre in real life. In the public space of the city. To shatter the habits of the passers-by.’ The superheroes kept quiet. They looked down pensively at the plastic table or up to the blue sky. Geert Opsomer nodded. ‘Yes, because that too will change us again.’

A month is too short to make a soft cartography of the territories of new-urban creation. But long enough to walk through Brussels and see that something is changing. An empire is crumbling. Villages are emerging. You can also call them heterotopias. Or rhizomes. With artists who expose themselves to the city. They are not content with the existing production conditions. To change them is inherent to the artistic work that they do. As a result the city is changing, but also the work itself. And not least, they themselves, the artists. They surrender their authority. They operate in a sense selflessly. But remain indispensable. Because they are the ones who, in a flash, simply by saying that it is possible, turn the streets and squares and parks of the city into a boulevard of possibilities.

And on the last evening of my month in Brussels, Luc Mishalle stands on a wooden elevation, as the conductor of MegafoniX, in front of Recyclart, under the tracks of the train station Kapellekerk.

A hundred and fifty musicians and singers, from children to seniors, with all the colours of the city. The square is full of people in the most generous party mood. The hour-long composition moves from Latin-American lullabies to battle songs of the Balkans to rai with a scratching DJ. A metre-high party skeleton, complete with crown of flowers, moves through the crowd, but Monsieur Luc does not let himself be distracted and continues undaunted to the finale. The square is ablaze, the pride resonates off the orchestra members, the public doesn’t stop clapping, Mishalle perceives each false note and excuses it immediately with that smile that is not to be wiped off his face, his white curls still sticking out just above the crowd.

It’s been great, Brussels. I have seen the barriers and the smugglers. I have seen a city that is greater than itself and smaller than necessary. Squares with wise men in wheelchairs and dancers who follow the choreography of the streets. Border areas that you don’t see but do feel. Churches and quays. Failed attacks and exultant concerts. Academically trained burglars and clairvoyants of the street. I can’t wait to see all that has changed by the time I return.