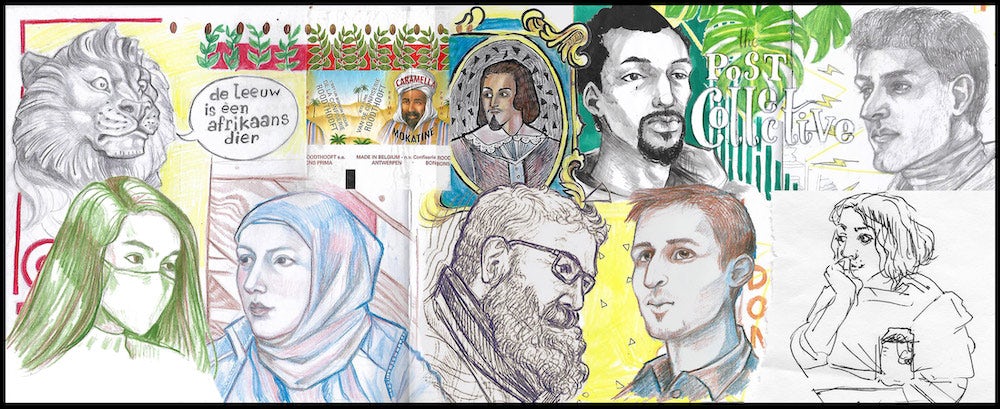

Ruimte voor kunst – case #9: The Post Collective, building spaces for change

What does workspace mean for you as an artist, if you are not sure where you will find a bed for the night? Is it physical space that matters for an artist to be able to create, or rather the legal space in which to operate? Is working as an artist about creating art or about carving out space in society for yourselves as a group?

These are just some of the topics that emerged in an encounter with The Post Collective, a platform for co-creation, co-learning and cultural activism created by and for refugees, asylum seekers, undocumented people and their allies.

The Collective was sparked off by the ‘Open Design Course for Refugees and Asylum Seekers’ at KASK School of Arts in Ghent in 2018, when some of the alumni and teachers decided to continue working together.

In October 2020, a seminar was held at Kunsthal Gent: The Transformation of the Art Space as Politics. Four people from The Post Collective attended the seminar and gave a presentation. They started off by singing out their names for several minutes. It was a very touching manner of demarcating their space.

Sound poetry is one of the ways in which The Post Collective manifests itself, but at the core of their work is the creation of alternatives beyond and against the dominant system of control and exclusion that refugees, asylum seekers and undocumented people are faced with. It is also about creating a network of care.

The fluid boundaries of art

I meet up with Elli Vassalou and Mirra Markhaeva in a small office in the old Actiris building (Hacktiris) in the centre of Brussels. We keep the windows open and our masks on, given the coronavirus measures. Marcus Bergner joins us online. Mahammed Alimu was also supposed to join but he was called for an interview as part of his asylum procedure.

Marcus starts by saying it’s great that I saw the video of the presentation at Kunsthal Gent. “It makes it clear that we all come from very different perspectives and backgrounds,” he says. “There are going to be a lot of polyphonic answers in this conversation.”

“Contradicting each other is part of our practice,” Elli says, laughing. “We are all in this together, but we are not one and the same,” Marcus adds. “That’s the basic mode of operation that we apply to culture, our engagements with each other and with the world.”

It sets the tone for the conversation.

When you talk about cultural activism, what do you mean by that?

Mirra: “All culture and art are a reflection of the world’s situation that we are in, but cultural activism is a more conscious reaction to and reflection on things that are happening around us. For me today, even just practising my culture in such a multicultural place is a kind of activism because somehow you introduce yourself into the occupied space. Apart from that, it’s about creating art that cares.”

Elli: “If we look at what contemporary art usually does – looking at relational aesthetics for example – it points out a problem in society, raises awareness and produces reflections. For me, cultural activism is not only about staying at this level but about trying to create spaces that contest all these problems in society and really try to enact solutions. The speculative design aspect in our work is strong.

“We are a group in which not everyone has civil rights. We try to work through that. In doing so, we manage to create space for people who face such exclusion. We are not doing a project about the idea but are actually trying to make it happen.”

Do you think the arts are a privileged space for giving voice to people without papers?

Elli: “What art provides is a connection with society that is more fluid than, for example, it is in politics. The borders are more porous, more open. When we put ourselves forward at Kunsthal Gent for example, they were very interested in this in-between space in which we operate.”

“In practical terms, it means that half of us can be paid legally and the other half can’t. We find ways around that. The economic model we are inventing is acceptable in the field of the arts, but it would be more difficult in other sectors. Art is a window for a lot of things that society is not ready for yet.”

“That doesn’t mean that all art institutions are open to this, but in general: yes, there are certainly more openings in the arts than anywhere else.”

Space is a resource

Your residence at Kunsthal Gent was interrupted by the pandemic, I assume. What happened to the collective during this period?

Marcus: “We wanted to focus more on our manual. The residency was intended to give us the time and space to understand our identity as a collective better, in terms of what we stand for and how we operate, but suddenly that was all put on hold because of the lockdowns. And we are still looking to develop the manual.”

Elli: “It’s sort of a code of conduct with a set of rules and values – but we don’t want to call it that because it has a rigid ring to it. We call it manual of care. It goes from agreements on how we get paid and what stays in the collective, to how we organise our assemblies and how we deal with our caring practices. Each of us has very different needs and very different positions in the group.”

“For example, Alimu was called out for an interview today in his asylum procedure. You cannot ask him to be present here when he has to go and do that. Sawsan is a mother, she cannot join us easily and usually participates online. You have to manage to work in the collective with all these specific needs. How we maintain the collective is part of our design and artwork.”

Mirra: “I also want to bring the immigrant aspect into this conversation as well as the artist aspect. Covid took away from us the visibility that Kunsthal Gent had given us. It’s in the middle of Ghent: a residency like that would make our dialogue with Belgian society possible.”

“For many people, the term ‘immigrant’ is an abstract idea they only know from the news. To meet us, to hear us, to see the fruit of our work, is really very important. We have now been pushed back into a space online. It’s a shame.”

How did The Post Collective first come about?

Elli: “The first idea for the Post Collective was created at the Open Design Course (ODC) at the KASK. There was also the Transnational Alliance of schools that was very important for us. We Cannot Work Like This was a collective project over the course of a year, with several departments at academies and universities in Belgium, France, England and Hong Kong taking part.”

“The central question was how to work together on a proposal for sustainable, decolonial and inclusive practices in relation to cultural institutions on the one hand and our own professions (design, architecture, artistic research) on the other. At a certain point we were invited with the ODC to present something at Contour 9 in Mechelen and we decided to take The Post Collective there. Our first manifestation took shape in that environment.”

“The KASK has not been our only ally, by the way: there are also other institutions, particularly Sint Lucas Antwerp which still provides resources, network and hands-on solidarity.”

Papers and hierarchy

What happened for you in those first months on the Open Design Course at KASK?

Mirra: “We all came to it in a different way, but for me the most important and impressive thing that happened was the connections being made and the community being built. I had the opportunity to join in with a group activity that I am normally excluded from because I don’t have any papers. It gave me some resources. Space is a resource.”

Is it hard to make connections when there is no space to start from?

Mirra: “Well, yes. My biggest problem as an immigrant is that I am restricted to boxes and specific spaces created for immigrants. There are lessons for immigrants, for example. I have taken lots of them. Often the outcome is that nothing changes, because you stay in the little box that has been created for you. The government is willing to give you some money and then you are supposed to stay in the box and that’s it.”

“That means that you don’t create real connections with Belgian society. It’s very difficult to break out of it. I don’t like the word ‘integration’, but in my view the actual integration starts when you participate in society, not when you stay in the box that has been created for you. If I can be perfectly honest: the ODC did this too, in a way. But it was a little door into society nevertheless.”

Elli: “The ODC is a three-month project. The school doesn’t yet have the structure to provide a follow-up after that, so we decided to create a vehicle for ourselves. A sort of ‘weapon’ as Marcus would say – to continue. We don’t need people to do things for us, but we want to be able to participate in society. We are a de facto part of it, although some of us don’t have the papers to legitimise that.”

Why do you call it a weapon, Marcus?

Marcus (laughs): “It actually comes from the title of a poem by the Basque writer Gabriel Celaya: Poetry is a weapon loaded with the future. ”

“I was on the course with Mirra. I had no papers at the time and was awaiting a visa application decision. The three months at KASK were an amazing exercise in collective storytelling. The things that happened outside the course were the agencies that were really bonding for me.”

“Apart from the courses we took – which were interesting – it was the form of attention we paid each other that was totally unique. It reminds me of what Simone Weil said about a kind of attention that is the rarest and purest form of generosity. After three months of the course, it was almost impossible not to start a collective.”

Elli: “In 2016, Sawsan was a student in the very first version of the ODC. I was doing my master in autonomous design at the time. After working for a few months in the Self-Organised Structures for Refugee Reception & Treatments on Lesbos in Greece, I came back to school, worked voluntarily as a mentor at the ODC and devoted all my work and writing to an autobiographical exploration of exclusions and inclusions in art education.”

“In 2018 Sawsan and I got jobs as teachers in the ODC. And then, the following year, Mirra started teaching as well. This is an interesting way of working and creating community at the ODC: previous students become part of the teaching team. The students also have their transport refunded, are offered lunch and receive a small production budget for their projects.”

A school that devotes space within its structure to people lacking the right papers to take part in the activities. Could that be a model for other institutions as well? A hospital? A bank?

Elli: “Actually, Alimu is a doctor. During the first lockdown, Médecins du Monde made a call for doctors and nurses. We responded that Alimu wanted to help but they said no: we cannot employ him in any way, not even as a volunteer.”

Mirra: “I would not say that all institutions should replicate the ODC’s model. There are some mistakes that can be learned from as well. Yes, it’s a place of experimentation, but it’s still part of an organisation run in a hierarchical way. We are not just beggars: we bring in resources with our ideas, work, information, skills, etc.”

“It’s a question of political will for every institution, but also at every level. The ODC was the brainchild of Bram Crevits, who was a teacher at the KASK. Sadly he died, and with him the initial drive to work in a peer-to-peer manner disappeared. The hierarchical decision-making soon came back.”

“When I was accepted as a student at Sint Lucas Antwerp, it was not thanks to the school itself but because of decision-makers higher up. Without their help, it simply would not have been possible for me to study without papers.”

Somebody has to stick their neck out, you mean?

Mirra: “Yes. It somehow has to be made official, it’s all about political will.”

They gave us the keys!

How was your experience at Kunsthal Gent?

Mirra: “This was one of the most positive experiences we have had with a Belgian organisation. We wrote an application and signed a few papers and that was it. There wasn’t a bureaucratic mess for us to go through. They didn’t require any identity cards from us. They gave us free access to almost the whole space.”

Elli: “And we got the keys!”

Mirra: “Yes! For me as a paperless artist… I have never been given so many resources to work with. And besides that, they were very appreciative of us. It absolutely felt like an equal exchange. I didn’t feel like I was a seeker or a demander. I think this is how it should be.”

I imagine that in a dynamic like that, there is a minimum loss of energy and a maximum capacity to create and connect?

Mirra: “Exactly. They took away the stress: I will have a place to work tomorrow, I will have access. They also took away a lot of technical worries that I carry around everyday. It gave me the mental freedom to concentrate on my work. It’s so basic really: you cannot expect artistic creativity from a person who doesn’t know if there will be money for food and rent.”

Elli: “For me the most important thing that Kunsthal Gent did was to trust us. The keys! They gave them to us! Usually if you don’t have papers, you are distrusted. At Kunsthal we were equal to all the other artists. Apart from that: they really care about the artists. Danielle (van Zuijlen, artistic coordinator of the Kunsthal- EDG) came to talk to us very regularly about how we were and what was going on.”

“She even did that in the Covid lockdown.We were no longer there physically, but we still felt very connected. We ended up getting a second period in the autumn, so we got the residency twice, and there is already talk of a public occasion in the spring for us to present our work so far.”

“We feel very welcome to go back. It has become a bit like a family home. We feel like we can make suggestions. This is quite unique. I have also done residencies in other places. Usually they dedicate an amount of time to you and then they move on to the next artist.”

Marcus: “My experience of the Kunsthal Gent provided some special autobiographical aspects and opportunities, mainly because of my long-term fascination with art history and in considering alternative ways of approaching it as a discipline. In recent years I’ve become increasingly pessimistic and doubtful about the relevance of contemporary art as a category or genre of art, and I think that it has outlived its usefulness.”

“We should move art into a post-contemporary period and attitude. So to have the residency in a contemporary art space that is actually located within a 14th century monastery at the Kunsthal was an opportunity too good to be true and utterly unique. That this space also includes what is called an ‘Endless Exhibition‘ seemed to connect to the Christian and monastic aspirations of achieving an eternal afterlife.”

“Anyway, being there for almost a whole year as part of the collective, whenever the pandemic permitted, was a very rewarding experience and a very untimely one, on many different levels. Much more so than if we had had a residency in the usual, neutralised, contemporary art space. The curators at the Kunsthal are very open to reflection and dialogue on the nature and function of such art institutions, something we also really appreciated.”

Network of care

Can you share a magical moment with us from your collective practice?

Mirra: “The first thing that comes to mind for me is from when I got sick. For the first few days I was really distressed. When you are an immigrant and you are ill and totally alone, you feel terrible and depressed. And then suddenly I received all this fruit, books and nice notes.”

“And it wasn’t just any fruit, it was my favourite fruit. I very actively felt the value of being part of a community at that point.” (smiles)

The collective is an important space, not so much in the sense of bricks and walls but mostly in the form of a network?

Elli (nods): “My magical moment was with Sawsan. She had to go into hospital at a certain point. She couldn’t see her little boy. Orkid is three or four. We asked what we could do to help.”

“She said: send something to Orkid. Someone got a book, other people got fruit and toys, I put everything together in a basket and gave it to Alimu. He brought it to Ghent where someone else picked it up and drove up to the house, knocked on the door and left the box on the porch. A magical present for the boy!”

“The day after we got a video of Orkid receiving the basket. Ten people did a small thing and made a boy and his mother happy. It was so wonderful to see that we have actually managed to build a network of care. Sawsan asked for something and it happened like this.” (snaps her fingers)

Marcus: “Last Friday was quite magical for me. We did a performance at the Royal Park in Brussels that was online and live on site at the same time. We have been running online voice practices since the start of the Covid crisis. We used to perform together at the Kunsthal, but now we do it online and recently also out in the world, simultaneously on our mobile phones, while others are at home on their computers.”

“On Friday participants from Brussels, Berlin and Dublin joined two of us performing in the park. I have been doing this kind of work in sound poetry and voice-based performance for many years, but last Friday produced something really quite special.”

“Everyone worked in their own languages and also made wonderful abstract vocal noises, all on Zoom. In the middle of this telephonic park performance, other park users were walking around us, talking into their phones, oblivious to what we were doing, which made them appear to be sleepwalking sound poets.”

Elli: “With the work that we do, everybody speaks in their own language. That creates togetherness that transcends a lot of barriers.”

Marcus: “For me, waking up in a collective after the coronavirus hit was really special because it gave me a lens to look at the situation the world finds itself in. It made me realise the need for collectivity globally. It also gave me a capacity to relate to what was going on.”

“It allowed for a collective imagining, let alone thinking and acting. Everyone is being told to be more collective-minded in terms of regulations and social distancing. But through the collective I realised that what we were doing with our practice of care and of attention was the basis for how to move forward as a society. To change the conditions that got us here.”

Mirra: “Being part of a collective is a survival strategy for me. Without my collective I don’t have a home; I don’t have access to education. Apart from that, we have more power of resistance as a group, we are more valid somehow.”

“There is no citizen power if we all live in our apartments without knowing our neighbours. Building connections is smart in lots of ways, not only as a way of survival but also as a political strategy. We have more chance of being heard when we form a collective.”

Ella: “For me it’s a very deeply feminist and decolonial practice to work collectively. The privilege of functioning as an individual comes from the fact that there are other people – whom you don’t even know – who are working for you. You have the privilege of using resources that are invisible to you. That is not the case for many people.”

“That is why all the maintenance work in our collective is made visible and is considered part of the artistic work. This is also why we are working on a code of conduct: a set of rules that all start with respecting one another. Solidarity and transparency are really important starting points for us.”

Creating space for fair practices

What would your ideal space in the future look like?

Elli: “Let me give you an example to answer that. We have been doing a lot of research on how to pay our artists. If you want to pay people fairly – as every artist should be paid – it’s quite impossible to find structures to support that.”

“The question is: how can you find legal ways to pay people who don’t have a legal status? Asylum seekers, for example, can work under a volunteer contract. So, okay, you can make 1500 euros a year as a volunteer, but obviously you can’t live on that. If you were paid equally that would be ten days’ work (assuming you are not paid a refugee salary of 30 euros a day).”

“There is also the KVR – the small fees for artists scheme – as a tool but you need an artist’s card to use that scheme. We applied for one for Alimu. We translated everything: it does not say anywhere whether or not you can apply for an artist’s card as an asylum seeker. This is simply something that no one has thought of. We are very curious to find out what happens when his case is evaluated.”

“For me, doing these things is also about creating space. It’s about doing things that haven’t been done before. What form might we use to help people work legally in this irregular situation? We cannot stop border politics or national space, but we can question what kind of space the artist can create.”

“Take the artist’s card, for example. I’m not sure how it started but they must have thought: artists cannot be self-employed so let’s create a tool. Maybe a tool like this can also be created for asylum seekers.”

“To come back to your question: a space in the future will have created this kind of collective solutions. If we haven’t managed to change the world by then, at least we will have some tools to be able to pay people for their work.” (smiles)

Do you have any recommendations you would like to make?

Marcus: “More openness to allowing people who are supposedly ‘illegal’ to receive payments and be allowed artistic status. I am more optimistic than Elli about the changes we can bring about (laughs). I think it’s important to see that the world can change through such actions.”

“I feel there is an opportunity now that hasn’t been around for quite a long time. I was always focused on the abolition of borders and the eradication of neo-colonial apparatus. Now, with Covid, it really feels like there is a momentum for a radical reset and replacing the old systems.”

“There is a worldwide awareness of the predicament that we are in. This could lead to more awareness in general. I’m not as pessimistic as I was before. Waking up in this collective has not only given me a platform, but also a real mindset focused on instigating and investigating alternative social structures. Commonism is coming!”

Mirra: “Karl Marcus the ‘commonist’!” (laughs)

“When it comes to recommendations: I really think that open spaces for the arts could be a tool for integration in immigration politics. The absence of legal formulas for refugee artists creates more segregation and makes the problem last longer. “

“More generations are affected, more complications created. In my view it would probably be cheaper to support immigrant artists straightaway, so that they could be productive sooner rather than later. Instead of putting them in boxes with other refugees, let them reach out to galleries and art spaces so they can really integrate into society and come into their strength.”

Elli: “A lot of organisations right now are preoccupied with fair practices. I also work at Globe Aroma (open arts house in Brussels – EDG), where we have also been working on this in constellations of organisations. Should we work with the KVR? Volunteer contracts? Bitcoins?”

“It’s actually a crooked way of fixing things. Like putting a band-aid on a wound. I really think that there is a momentum now to think about these things seriously along with the institutions and the policymakers. Just as the artist’s card and volunteer contract were created to make things possible, maybe there could also be a tool developed to make it possible for refugee artists to receive payment for their work.”

“Let’s create a legal space for artists who don’t have a resolved civil status!”

So The Post Collective is not so much about a physical space as about carving out space in society?

Marcus: “I feel that the collective is a public space. I find that very liberating in these times of continuous privatisation of public space. There’s a quote from the architect Lebbeus Woods we used in our introductory notes for the residency that I think reflects the way we approach the societal potential and function of space.”

“The only thing that is radical is space that we don’t know how to inhabit. This means space where we have to invent the ways to act and to live.”

Elli: “I would rather say: it’s about carving out a space of our own. In all this chaos there is no space for some people, so we have created it ourselves. Mirra said something interesting the other day: my presence is making space; my presence is transforming space. The Post Collective is not a physical space, it’s an ideal space that tries to transform the spaces it interacts with. At Kunsthal Gent we have already experienced this fusion.”

Mirra: “There is one more thing I’d like to add. Many of us come from a place of trauma, the kind of thing that people who have privileges by birth often do not know about. Some of us have suffered major trauma, and others come from very dark places. That’s why it’s important that the space we create is a space of care, support and solidarity.”

“Apart from that, the space we are creating is also about creating passages. We are nomads navigating the labyrinth of the Belgian system and we are trying to find doors that can be opened, just a little.”

“We hope to make the system more open, create corridors and windows. Change rarely comes from institutions. They are organisms that want to preserve themselves. It’s the demand that brings changes. We are building spaces for change.”

More information

The Post Collective is Mirra Markhaeva (Buryatia), Sawsan Maher (Syria), Marcus Bergner (Australia), Elli Vassalou (Greece), Mohammed Tawfiq (Iraq), Mahammed Alimu (Somalia) and Hooman Jalidi (Iran).

Globe Aroma is an Open Arts House for newcomers, refugees and asylum seekers. Globe Aroma offers space, time, creative support and a network to artists, creatives and culture lovers. The Open Arts House is a low-threshold artistic sanctuary centred on dialogue, collaboration, networking, creation and cultural experience.